Cyclosporin mold's 'sexual state' found in New York forest Cornell students' discovery could target additional sources of nature-based pharmaceuticals

By H. Roger Segelken

Until Cornell University undergraduate students on a mycology field trip found mysterious fungal "fruiting bodies" rising from an eviscerated beetle grub, little was known of the mold that produces a life-saving pharmaceutical for organ transplantation -- the immunosuppressant, cyclosporin.

Now, Tolypocladium inflatum, the white mold from Norway that makes cyclosporin and other biologically important compounds, is out of the closet, so to speak, as reported in the September-October issue of the journal Mycologia. In its sexual state, T. inflatum is actually Cordyceps subsessilis, an extremely rare fungus that has been reported only five or six times before.

Knowing the true family history of T. inflatum/C. subsessilis will help target the search for other nature-based pharmaceuticals, according to Thomas Eisner, the Cornell biologist whose Institute for Research in Chemical Ecology (CIRCE) will send "chemical prospecting" teams into the world's first temperate zone biodiversity preserve, less than a mile from the woods where students found the fungal fruiting bodies. One close relative of C. subsessilis already is known to Chinese athletes as the performance-enhancing "caterpillar fungus."

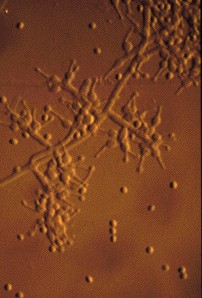

"There are so many molds that we don't know the life cycle of. All the cyclosporin in the world -- for hundreds of thousands of transplant patients who need anti-rejection drugs -- has been made from Tolypocladium inflatum cultures without that mold ever reaching the sexual state," said Kathie T. Hodge, the Cornell graduate student of systematic mycology who identified the New York fungus for what it is. "T. inflatum is commonly found in soils, but it does not make the sexual state without very special conditions -- until it is on its favorite host -- which seems to be the dung beetle."

For Professor of Mycology Richard P. Korf's "Field Mycology 319" class one fall afternoon in 1994, the assignment was simple: Pick up everything interesting-looking in Michigan Hollow State Forest, in Danby, N.Y., and wrap the fungi in waxed paper. They were to return to the Cornell lab where graduate teaching assistant Hodge would try to help identify things that anyone but a mycologist -- or a student of the subject -- would consider extremely disgusting.

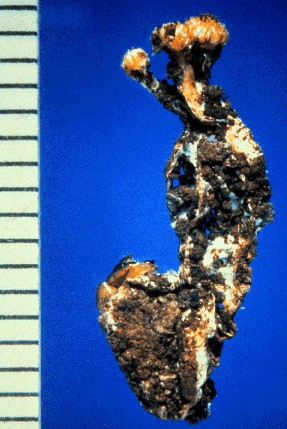

Indeed, the yellow, finger-like fruiting bodies growing out of the backs of two grubs from Michigan Hollow were enough to give fungi in general a bad name, even before they received a name of their own. For one thing, the fungus had consumed so much of the grub that entomological identification was impossible without the help of a specialist. (The unfortunate grubs eventually were determined, by Cornell Associate Professor of Entomology James K. Liebherr, to be the larvae of a type of scarab beetle that feeds on organic soils and dung, although there was not enough grub left to exactly identify the species.)

By studying the physical appearance of the fruiting bodies and consulting with Richard A. Humber, a research entomologist at the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Plant Protection Research Unit in Ithaca as well as an adjunct associate professor in Cornell's Department of Plant Pathology, Hodge determined that the students had collected the rarely seen C. subsessilis. Then she germinated spores from the fruiting bodies and grew the same white mold that produces cyclosporin. The identity was confirmed when Stuart B. Krasnoff, an entomologist in the Ithaca USDA lab, detected the presence of efrapeptins, the "signature" chemical compounds that are produced only by Tolypocladium species.

"This is an incredible find," said Eisner, the Jacob Gould Schurman Professor of Biology and one of the founders of the scientific field of chemical ecology. "This tells us to look at other, related species of this fungus for potentially useful compounds. And we've only begun to look," he said, noting that an estimated 90 percent or more of the world's fungi have yet to be identified, scientifically cataloged and examined. (One that is better understood, because its use became controversial in international track and field competition, is dong chong xia cao, better known as the caterpillar fungus. Tonics made from the fungus, which is traditionally sold in small bundles of fungus-infected caterpillars, reportedly are responsible for record performances by some Chinese athletes. The Chinese caterpillar fungus is Cordyceps sinensis.)

In the meantime, spores from the properly identified Michigan Hollow fungus are sleepless in Ithaca, chilled to dormancy by liquid nitrogen in the Agricultural Research Service (ARS) Collection of Entomopathogenic Fungi. They are part of the world's largest collection of fungi that kill insects. Hodge, now a fourth-year Ph.D. student who is working as a volunteer with the Finger Lakes Land Trust, is trying to identify as many fungi as possible in the Temperate Zone Biodiversity Preserve in West Danby, N.Y.

But who gets credit for picking up the beetle grubs with the elusive C. subsessilis?

"No one knows, really," Hodge said. "We were just collecting fungi as fast as we saw them, and no one remembers getting this one."

So Hodge added a special acknowledgment to her Mycologia article: "We also thank students in field mycology classes everywhere for picking up interesting things."

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe