Fidelity is key mate-preference factor for both sexes, Cornell students learn

By Roger Segelken

Not looks or money but rather life-long fidelity is what most people seek in an ideal mate, according to a Cornell University behavioral study that also confirmed the "likes-attract" theory: We tend to look for the same characteristics in others that we see in ourselves.

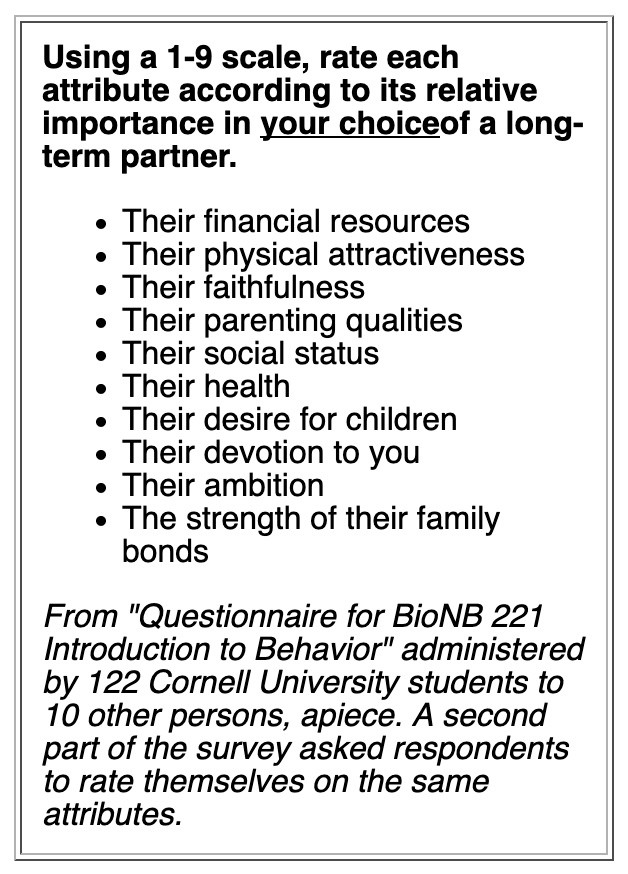

The study began when Cornell University students in an animal-behavior class conducted a scientific survey of 978 heterosexual residents of Ithaca, N.Y., ages 18-24. Hoping to learn whether likes attract, students asked their male and female survey subjects to rate the importance they placed on 10 attributes in a long-term partner — and to rate themselves on the same attributes.

The student-gathered results, reported by their instructors, Peter M. Buston and Stephen T. Emlen, in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS early edition July 1, 2003), are raising eyebrows among scholars of evolutionary psychology, making news and sparking debate around the world.

"The last time I checked the CNN online poll, about 33 percent thought we were dead wrong — at opposites do attract," says Emlen, a Cornell professor of neurobiology and behavior whose fieldwork concerns mating preferences of African birds.

In fact, the "likes-attract" issue debated in CNN's admittedly unscientific QuickVote poll (beneath a photo captioned: "Actor Brad Pitt and wife Jennifer Anniston have similar looks.") was only part of the story. The researchers did report in PNAS that human mating decisions are "… based on a preference for partners who are similar to themselves across a number of characteristics." Just as interesting, Emlen thinks, are which characteristics are rated as most important.

"Surprisingly, physical attractiveness is not all that important — except to people who rate themselves as physically attractive, the Brad Pitts and Jennifer Annistons of the world," says the 62-year-old professor who has been married to the same woman for 30 years. "What Dan Quayle infamously called 'family values' characteristics -- good parenting qualities, devotion and sexual fidelity — that's what people say they're looking for in a long-term relationship. And most people say they perceive those same characteristics in themselves."

Some theories of animal behavior have suggested that so-called lower animals — if not humans — look for attractive physical qualities, such as bright plumage or shiny coats, because outward appearances can be a sign of reproductive health. And a potential mate's wealth -- a large, well-built nest and ample food, for example — might advertise an animal's ability to provide for the offspring that will carry its genes. Without discounting those mate-choice preferences in the animal world, Emlen thinks humans have evolved to play a more sophisticated mating game. "It's clear from this study that people rate fidelity and family values quite high," he says. "They see these characteristics in themselves, and they look for them in potential mates."

Actually, the finding wasn't all that clear, in the fall of 1999, when 122 Cornell students in the extra-credit discussion section of BioNB 221, Introduction to Behavior, each administered questionnaires to 10 other people (see sample question, above). The survey was voluntary and anonymous, and after eliminating results from respondents who said they were gay or bisexual, the students had data from 979 heterosexuals — primarily fellow students. The Introduction to Behavior students wrote reports for the class at Cornell, which emphasizes research opportunities for undergraduates, got their grades and went on their way.

Buston and Emlen were left with an intriguing, if unsorted, mountain of data. The scientists put the results aside for several years then performed various statistical analyses, "and it jumped out at us," Emlen says. As reported in the PNAS article, which graciously credits students for doing all the legwork in the study, "… humans use neither an 'opposites-attract' nor a 'reproductive-potentials-attract' decision rule in their choice of long-term partners but rather a 'likes-attract rule."

Emlen says he hopes the paper will inspire social scientists to mine previously collected data, to test the main prediction of the study: namely that marriages between partners who are similar across many characteristics will be more successful in terms of marital satisfaction, duration and child well-being than those between more disparate individuals.

Meanwhile, Buston, who now is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California-Santa Barbara, is in Spain. His doctoral research at Cornell involved behavioral studies with the starring species in the family-values-rich Disney picture "Finding Nemo," the clownfish.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe