An amazing book drive from Ithaca, N.Y., to Vilnius, Lithuania

By Franklin Crawford

How do you rebuild a library from scratch? One book at a time.

For the past several years, Jane Marie Law has been helping to help stock the empty library in the Center of Oriental Studies at Vilnius University in Lithuania, one of the oldest schools in Europe. In November Law, Cornell University associate professor of Japanese religions and director of the Asian religions Ph.D. program, hosted a visit from Audrius Beinorius, head of the Vilnius center. She had a simple plan: ask friends and colleagues if they had duplicate books on Asian studies or could simply spare books they no longer needed and then sort through them with Beinorius. The response was tremendous.

Faculty, curators and even graduate students culled their collections, and more than 2,000 useful books were collected. Beinorius was overwhelmed with gratitude by the gesture.

"This will help us very much," he said. "When we reopened in 1993, we started from zero. We are greatly lacking in secondary sources and critical studies and [these contributions] will really help us proceed with our teaching."

The center is the major institution of Asian studies in Lithuania as well as an academic core unit of Vilnius University. Studies focus on the regions of Asia and Near East, and the center serves as a link among the Lithuanian researchers of the East. The center's teachers endeavor to prepare specialists in the field of Asian studies needed for scientific research, the development of cultural and business relations as well as to promote better understanding of the Eastern cultures in Lithuania, and to foster collaboration between the East and the West.

But few institutions of higher learning have withstood as much turmoil as Vilnius University. Founded in 1579, it is one of the oldest universities in Europe. But its history, as that of the Baltic region in general, is marked by chronic tumult. In 1832, Vilnius University was closed by czarist Russia, and many of its holdings were scattered throughout the empire. For years the Russians tried to immerse Lithuania in Russian language and culture but were fiercely resisted. Vilnius reopened in 1919 after the region now known as Lithuania became an independent nation for the first time.

According to the center's Web site, in the period between the world wars, Vilnius University – under the name of Stephan Batory University – resumed limited Oriental studies and shared its facilities with such Polish scholars as the famous Japanologist Bronislaw Pilsudski.

In 1939, the Nazis came in and plundered the school and if that weren't enough, the Red Army followed and Lithuania came under Soviet control. Scholars at Vilnius had a tough job of holding on to what little they had left. They were not allowed to teach Asian studies at Vilnius under the Soviet regime. But Lithuanian students and scholars were allowed to pursue Asian studies in Moscow and St. Petersburg. Many of the once rich resources of the entire school are in Russia, and Beinorius said it is nearly impossible to get them back.

But Vilnius never gave up. Today the university is run by top research scholars and attended by thousands of students, many of them first-rate graduate students in a number of fields, said Law.

The program headed by Beinorius was originally founded in 1810, the first of its kind in Eastern Europe. It was pretty much dormant from 1832 until 1993, after Lithuania gained independence from the Soviet Union. Even with scant resources, the program still manages to graduate about 40 students a year, said Beinorius. Students often have to wait weeks for books on interlibrary loans with schools in other countries.

Attrition and conflict aren't the only reasons the center lacks books. Many of the materials previously in use at the center's library were rewritten in Russian and "almost no one reads in Russian any more," said Beinorius, "unless they have a Russian parent." Most of the students read and speak English. The school does get donations from other countries, particularly Asian embassies, but it is hard to come by secondary sources and often, while some primary source material gets delivered, there's a lot of unnecessary dross in the form of government brochures and "propaganda," Law said.

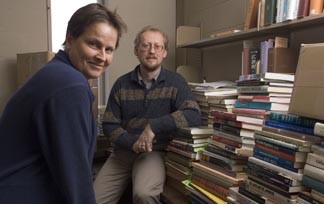

Law first became involved at Vilnius after delivering a paper there in 2003. She has since returned four times to present talks and will be co-directing a conference at Vilnius in May 2006. Her office in Rockefeller Hall as well as her study in Olin library became repositories for the hundreds of books that she and Beinorius sifted through individually.

Law also was gratified by the generosity of her colleagues, and the shelves in her own study are considerably thinned. Other Cornell Asian studies professors who contributed to the effort included Brett DeBary, Karen Brazell and Daniel Boucher, and Hairhin Diffloth, a senior lecturer in Korean language. Contributions also were made by John Whitman, professor of linguistics in the East Asia Program and Cornell University Library curators Thomas Hahn (China collections), Fred Kotas (Japanese collections) and David Wyatt, curator of the Echols Southeast Asia collections. A generous donation also came from R.J. Smith, professor emeritus of anthropology. Two doctoral students pitched in: Masaki Matsubara in Asian religions and Brian Brereton in anthropology. The steep tab for shipping costs will be picked up by the office of the attaché to the American Cultural Center in Vilnius.

As an international exercise in academic unity and good will, the week could not have gone much better. Adapting lyrics from a Randy Newman classic ("Simon Smith and His Amazing Dancing Bear"), Law said: "It's just amazing how good people can be."

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe