Chaos and commerce: Researchers find that Colombia's violence has damaged the nation's economic growth

By Anne Ju

Colombia has suffered decades of brutal violence engendered by revolutionary movements, drug cartels, private militias and street gangs. Street violence has affected not only the lives of everyday Colombians, but also the survival of such small businesses as shops, bakeries, garages and manufacturers. Yet Colombia also boasts rich natural resources, abundant gold and emerald production, and a relatively educated populace.

Two Cornell researchers, who have spent the last few years studying the impact of violence on the Colombian small-business climate, conclude that instability directly affects entrepreneurs' ability to prosper.

Wesley Sine, assistant professor of management and organizations at the Johnson School, and Shon Hiatt, a fourth-year Ph.D. student in organizational behavior, analyzed data from five Colombian cities and tracked the successes and failures of 1,000 small businesses in those areas from 1997 to 2007. They traveled to South America many times, interviewing hundreds of workers, families and entrepreneurs, while tracking rates of homicide, kidnapping and other statistical measures of violence.

Their report, "Declining Insurgencies," shows that violence – and the perception of violence – damages the country's economic growth on several levels, including the willingness of entrepreneurs to network, to grow their businesses and to innovate.

"When we first started the study, we focused on those types of behaviors that we thought would increase entrepreneurial success," Sine said. "But as we started collecting data and talking to people, it became clear that the general level of violence in a region plays a crucial role in shaping the behavior of entrepreneurs."

The good news is that since the decline of major insurgencies, such as the National Liberation Army (ELN), the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the paramilitaries, survival rates for small businesses have doubled since 2001.

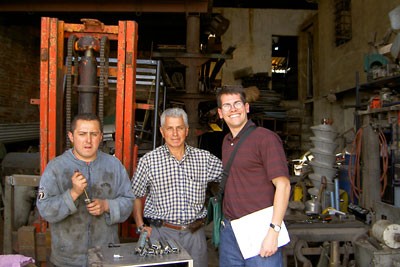

Sine and Hiatt began their work with data collected by a Colombian nonprofit organization, which from 1997 to 2001 surveyed about 1,000 small business, including bakeries, automobile repair shops, restaurants, convenience stores and small manufacturing shops. The Cornell researchers extended the data to 2007, forging relationships with business owners and observing how levels of violence affected them.

During the late 1990s, for example, the city of Medellín was wracked with violence associated with the ELN and FARC and the intervention of paramilitary forces. During that time, Sine explained, entrepreneurs lost their sense of trust, and often because no one knew who was doing the killing, they were afraid to do business with strangers or even to leave their neighborhoods. As a result, many small businesses failed.

Hiatt said he was most surprised by how entrepreneurs not only failed to network, but were also less likely to innovate. Violence levels affected the likelihood that entrepreneurs would introduce new products or services, or try to expand production or sales to new locations, even when factoring in the impact of the growing or declining economy. This was surprising, Hiatt said, because most of the entrepreneurs in the sample did not experience violence directly.

"Had it not been for this psychological effect, we probably would have seen a different result," Hiatt said.

Sine and Hiatt plan to continue their research on violence and entrepreneurship in other Latin American areas, including Chile and Mexico. Currently they are looking at how drug trafficking in Mexico, particularly along the U.S. border, affects small businesses.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe