CU wine conference addresses aging and keeping of wines

By Amanda Garris

It's an age-old question: How long will this wine keep? The answer: It depends on corks, storage temperatures and even ladybugs.

So said some of the 100 winemakers and enology experts gathered at the Ramada Inn in Geneva, N.Y., April 13-15, to discuss the differences between young wines and older vintages at the 40th Annual New York State Wine Industry Workshop.

They explained how chemical compounds and aromas change significantly as wines age and how winemakers' choices and new techniques developed at Cornell can affect these reactions.

Wines are often described as softer, more complex and less fruity with age. Much of this has to do with tannins -- compounds that can cause a wine to feel rough or smooth -- which change significantly over time.

Grapes ripen on the vine, but tannins ripen in the bottle, said James Kennedy, professor of viticulture and enology at California State University-Fresno. His research shows that the shape of young tannins allows them to easily interact with our salivary proteins to give a "dry" feeling, but with age, their molecular shape becomes more chaotic, interact less with our salivary proteins and are perceived as "soft."

Aromas may also change as wine ages in the bottle, said Gavin Sacks, Cornell assistant professor of food science, who explained how factors such as oxygen, pH and storage temperature influence the rate at which aroma compounds are formed or lost in white wines.

Bottle closures, such as natural corks, synthetics and screw caps, can affect wine flavor and aroma by regulating the amount of exposure to oxygen during storage, said Thomas Karbowiak of the University of Burgundy, France, and Glenn O'Dell, director of quality control at Constellation Brands. The right closure depends on the type of wine, the cost and even the expectations of the consumer.

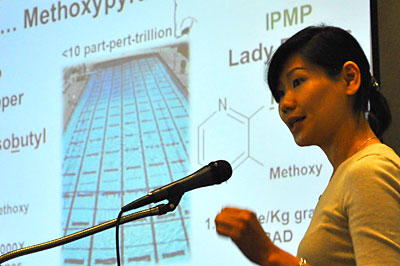

New techniques developed at Cornell can help manage or prevent undesirable wine aromas, including an inexpensive and accurate way to measure elemental sulfur pesticide residues on grapes and a new method to remove "ladybug taint" -- an earthy off-aroma that appears in wine made from grape clusters with a few stowaway ladybugs.

The workshop also featured talks on legal, regulatory and marketing issues, such as strategies for getting New York wines onto wine lists in New York City restaurants and a new labeling program developed by the industry to identify sustainably produced wines.

"This annual conference focuses on winemaking and its challenges in eastern, cool climate wine regions," said Anna Katharine Mansfield, Cornell assistant professor of enology, who organized the meeting with enology extension association Chris Gerling. "We were looking for a theme that reflected the fact that the New York industry is maturing and coming into its own, so we decided to address the issues involved in producing and understanding age-worthy wines."

Peter Saltonstall '75, co-owner of King Ferry Winery, was honored at the event by the New York Wine and Grape Foundation with a Unity Award. Director Jim Trezise said Saltonstall was instrumental in changing national and state laws to allow direct shipment of New York wines to other states, crucial legislation that allowed New York wineries to maintain direct relationships with their customers from other states.

The event organized and hosted by the Cornell Enology Program, Department of Food Science, New York State Agricultural Experiment Station in Geneva in cooperation with the New York Wine and Grape Foundation.

Amanda Garris is a freelance writer in Geneva, N.Y.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe