“... If I can help enrich the community’s understanding of their own place, that’s very rewarding.”

– Jeffrey Chusid

Jeffrey Chusid explores the fate of structures in times of change

By

In the summer of 1985, Jeffrey Chusid was offered an opportunity that would change his life. He was teaching architecture in a summer program for high school students at the University of Southern California when a call came in; Harriet Freeman, the elderly owner of a house designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, needed a tenant.

Only a few years out of architecture school, Chusid responded. He would live at the Freeman House, built in 1924 in the Hollywood Hills of Los Angeles, for the next 13 years.

Freeman bequeathed the house to USC when she died a year later, and the school planned to use the home to host distinguished faculty and events. Chusid stayed on to direct these efforts. “But, bit by bit,” he says, “we learned that the house was not good to go. It was falling apart.”

From that deterioration, Chusid discovered new talents and a new passion: preservation. “I was really good at understanding what was going on with the building and what we needed to learn from it,” he says. “And I loved the voyeuristic aspects of preservation – it’s an entrée into the private lives of the clients and designers, and it can tell you a great deal about the society and community that built the object, the artifact.”

Since those early days in the Freeman House, Chusid – associate professor and chair of the Department of City and Regional Planning in the College of Architecture, Art and Planning – has dedicated himself to finding and understanding the complex personal and political stories that buildings and structures around the world can tell us, stories that often pose difficult questions about what makes structures valuable and to whom.

The Freeman House

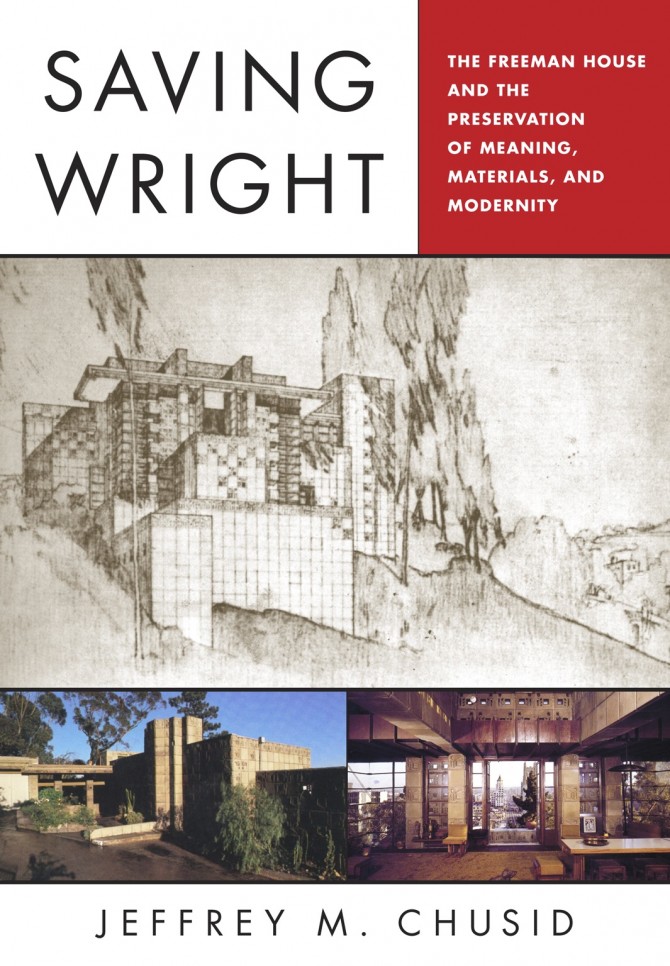

Chusid explores his time in the Freeman House in a 2011 book, “Saving Wright: The Freeman House and the Preservation of Meaning, Materials and Modernity.” In alternating chapters, he tells the cultural story of the house – how it fits into Wright’s career, how Samuel and Harriet Freeman came to commission the home, and the role it played in the community.

“Harriet and Sam were a part of the avant garde, so the house was a salon, and interesting people lived there as their guests,” Chusid says. “Martha Graham supposedly danced in the living room. During the McCarthy era, it was actually a refuge. So there’s a fabulous social and cultural history.”

Chusid also tells the more technical story of the various alterations made to the house over the 62 years the Freemans occupied it, many by prominent architects in their own right. Among the questions the book explores is how changes that have been made – and ones that still need to be made – to preserve the home alter the house’s identity as a Frank Lloyd Wright artifact. “What’s the level of intervention where the thing stops being the thing?” he asks.

Chusid’s stay in the house also made him an expert in a common material of modernist architecture: concrete. The Freeman House is one of a group of structures Wright designed in Los Angeles made of concrete blocks. “So I became interested in modernist buildings – their materiality, their design and the cultural narratives,” he says.

At USC Chusid began a preservation program that took up the ongoing issues surrounding the house. The program, which just celebrated its 25th anniversary, is run by Trudi Sandmeier, M.A. ’00, an alumna of Cornell’s program in historic preservation and planning. Following damage from multiple earthquakes, the house is undergoing reconstruction.

The ‘architecture of independence’

For his next book, Chusid found the perfect subject in American architect Joseph Allen Stein. Stein made his major contributions in the San Francisco Bay area in the 1940s and over a decadeslong career in India.

Stein was on the political left, and in 1950, his fear of arrest for communist activities drove him out of the United States. After three years of travel, he landed in the newly independent India, where he would go on to build one of the largest architectural and engineering firms in the country.

Different iterations of his firm built all kinds of projects – from the first high-rise in India to the influential and symbolic India International Centre to the iconic India Habitat Centre. A neighborhood in New Delhi even bears his name, Steinabad, due to the number of his buildings and his influence in the area.

For Chusid, Stein fits into a larger narrative of expatriates working in India as the country modernized after it gained independence in 1947.

“Part of what I’ve been very interested in is what I call the ‘architecture of independence’ in India,” he says. Chusid notes that Indian historian and writer Ramachandra Guha has said India’s history stopped once it gained independence – everything since then has been current events. “That has left a lot of important modernist work from early on in India’s independence, as it was establishing itself as a country, at risk of not being preserved,” Chusid says.

Stein’s work falls into this time period, and his buildings tell a complicated story. An example is the India International Centre, constructed in 1962. The building is a symbol of openness – designed for India to host visitors from around the world and made with materials from all over the globe. But it also points to a time in India’s history when the skilled labor force and manufacturing were underdeveloped, and opportunities were given to outsiders.

As these buildings age, and as they are repurposed in a more conservative political climate, the complexity of what they represent poses interesting questions in terms of preservation, Chusid says. “Is this a monument? How should we treat it? Why are we saving it? What stories does it tell us?” he asks.

Exploring these and other questions, Chusid is working with Cornell University Press on a book about Stein’s life and work. “This project is as much about understanding what his work means in terms of community, society and history as it is about architecture,” Chusid says.

Monuments, politics and conflict

Chusid’s work on Stein dovetails with projects he’s carried out around the globe. The thread that runs through them is trying to understand the fate of structures and monuments in complex political or historical contexts or in the midst of rapid change and conflict. These structures often tell stories of power: who has it and who doesn’t.

He has brought students to Levuka, the original colonial capital of Fiji, in the South Pacific. The conflict there between indigenous and long-standing immigrant communities – and the status of the city as a historical site – complicate both preservation and new construction projects. “Here, I became even more interested in what it means to have a community determine, identify and select resources and then determine their future,” Chusid says.

In Bosnia-Herzegovina, Chusid led a summer program for students around the issue of the Mostar Bridge, which had been very intentionally and symbolically destroyed in 1993, during the Bosnian War. The longest single-span stone bridge in the world, the original Mostar Bridge was built in the 16th century by the invading Ottomans. A campaign to rebuild the bridge provided Chusid and his students the opportunity to think about the monument, what it stood for and why it should be resurrected.

“That project drove home to me this paradox – of wanting to get people involved in their historic and cultural patrimony, but then you have to live with the consequences of their engagement and involvement and conflict over these monuments,” he says.

While monuments and structures can divide, Chusid has found that the efforts to save them can empower and galvanize a community, too. “When I go somewhere, it’s me and community members and a site, and that becomes incredibly rich,” he says. “I learn so much from them and find that I’m am still able to be changed by a place. And then if I can help enrich the community’s understanding of their own place, that’s very rewarding.”

Caitlin Hayes is a former staff writer for research.cornell.edu and now is a communications specialist with Cornell’s Center for Teaching Innovation.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe