Irish potato famine pathogen originated in Mexico

By Krishna Ramanujan

Settling a long-established debate over the origin of Phytophthora infestans – the pathogen that led to the Irish potato famine in the 1840s – plant scientists now conclude from genetic analyses that it came from central Mexico and not the Andes.

The analysis, by a multi-institutional team including researchers from Cornell, is important since knowing the pathogen’s origin will help plant breeders identify local plants with late blight resistance that might be bred into commercial potatoes.

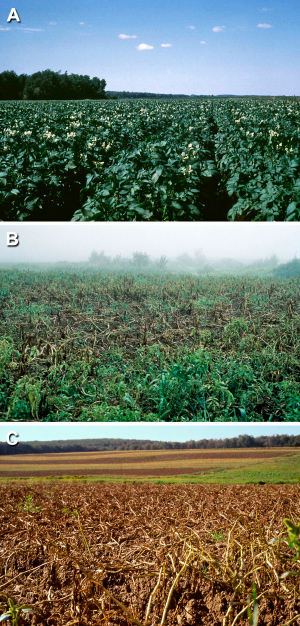

To this day, potato late blight remains a major food security threat and has been conservatively estimated to cause $6 billion of damage per year globally. P. infestans is a funguslike oomycete that infects leaves and stems, rots tubers and can completely destroy a healthy field of potatoes in just two weeks.

Published June 2 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the study reports how researchers identified the pathogen’s origins after sequencing four genes with important DNA fingerprints from more than 100 P. infestans samples from across the globe and from four closely related Phytophthora species to understand ancestral relationships.

Statistical analysis compared multiple loci on the four sequenced genes, which suggested that the pathogen originated in Mexico. Also, the results support a theory that populations of P. infestans found in the Andes migrated south from Mexico.

Very rarely do researchers identify the geographic origin of a plant pathogen, though geographic centers of evolution and diversity for crops are well documented. But by knowing the disease originated in the Toluca Valley of central Mexico, scientists can now study the coevolution of the plant hosts with the pathogen, and possibly develop more resistant crops.

“Populations of wild plants contain a wide array of resistance genes,” and along with no monocultures, lead to less severe disease outbreaks, said William Fry, professor of plant pathology and a co-author of the paper. Erica Goss, assistant professor of plant pathology at University of Florida, is the paper’s lead author, and Niklaus Grünwald, a research plant pathologist at the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Agricultural Research Service in Corvallis, Oregon, is the paper’s senior author.

A single clonal lineage of P. infestans had invaded the U.S. by 1843, and by the summer of 1845, the potato late blight had established itself in Europe – leading to the Irish potato famine.

P. infestans reproduces asexually, creating clones, and it also reproduces sexually, but until the 1950s, only one cloned lineage – called A1 – was known throughout the world, until the discovery of the A2 type in the Toluca Valley, where the A1 and A2 types were found in equal frequencies and sexually reproduced.

In the late 1900s, the A2 variety first appeared in Europe, likely through shipments of potato tubers from Mexico, and quickly dominated and displaced the A1 strains there.

Until the 1920s it was assumed that the pathogen originated in the South American Andes and arrived in Europe with the potato. But the late Cornell plant scientist Donald Reddick first suggested in 1928 that Mexico might be the source of P. infestans because resistant potatoes were found in central Mexico, but not in the Andes.

The USDA and several institutions including Cornell funded the study.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe