Mysterious 'Magic Island' appears on Saturn moon

By Blaine Friedlander

Now you don’t see it. Now, you do.

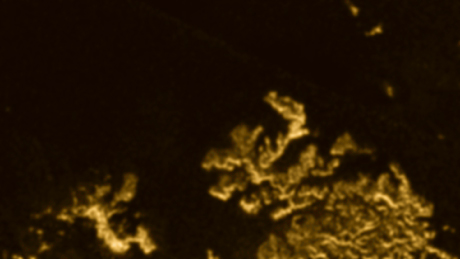

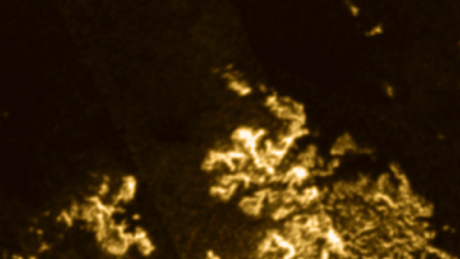

And now you don’t see it again. Astronomers have discovered a bright, mysterious geologic object – where one never existed – on Cassini mission radar images of Ligeia Mare, the second-largest sea on Saturn’s moon Titan. Scientifically speaking, this spot is considered a “transient feature,” but the astronomers have playfully dubbed it “Magic Island.”

Reporting in the journal Nature Geoscience June 22, the scientists say this may be the first observation of dynamic, geological processes in Titan’s northern hemisphere. “This discovery tells us that the liquids in Titan's northern hemisphere are not simply stagnant and unchanging, but rather that changes do occur,” said Jason Hofgartner, a Cornell graduate student in the field of planetary sciences, and the paper’s lead author. “We don’t know precisely what caused this ‘magic island’ to appear, but we'd like to study it further.”

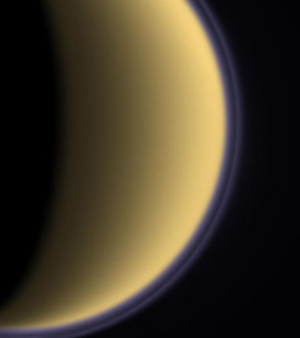

Titan, the largest of Saturn’s 62 known moons, is a world of lakes and seas. The moon – smaller than our own planet – bears close resemblance to watery Earth, with wind and rain driving the creation of strikingly familiar landscapes. Under its thick, hazy nitrogen-methane atmosphere, astronomers have found mountains, dunes and lakes. But in lieu of water, liquid methane and ethane flow through riverlike channels into seas the size of Earth’s Great Lakes.

To discover this geologic feature, the astronomers relied on an old technique – flipping. The Cassini spacecraft sent data on July 10, 2013, to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology for image processing. Within a few days, Hofgartner and his colleagues flipped between older Titan images and the newly processed pictures for any hint of change. This is a long-standing method used to discover asteroids, comets and other worlds. “With flipping, the human eye is pretty good at detecting change,” said Hofgartner.

Prior to the July 2013 observation, that region of Ligeia Mare had been completely devoid of features (including waves).

Titan’s seasons change on a longer time scale than Earth’s. The moon’s northern hemisphere is transitioning from the vernal equinox, or spring (August 2009), to summer solstice, or summer (May 2017). The astronomers think the strange feature may result from changing seasons.

In light of the changes, Hofgartner and the other authors speculate on four reasons for this phenomenon:

- Northern hemisphere winds may be kicking up and forming waves on Ligeia Mare. The radar imaging system might see the waves as a kind of “ghost” island.

- Gases may push out from the sea floor of Ligeia Mare, rising to the surface as bubbles.

- Sunken solids formed by a wintry freeze could become buoyant with the onset of the late Titan spring warmer temperatures.

- Ligeia Mare has suspended solids, which are neither sunken nor floating, but act like silt in a terrestrial delta.

“Likely, several different processes – such as wind, rain and tides – might affect the methane and ethane lakes on Titan. We want to see the similarities and differences from geological processes that occur here on Earth,” Hofgartner said. “Ultimately, it will help us to understand better our own liquid environments here on the Earth.”

In addition to Hofgartner, Cornell authors include: Alex Hayes, assistant professor of planetary sciences; Jonathan Lunine, the David C. Duncan Professor in the Physical Sciences; and Phil Nicholson, professor of astronomy. A portion of the research was performed at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, under a contract with NASA.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe