Expedition returns from Anatolia: 1908

Blizzards, bad roads, an “unsettled” country: challenges facing three Cornellians who sailed from New York for the eastern Mediterranean in 1907 were legion. But their 14-month campaign in the Ottoman Empire resulted in photographs, pottery and copies of numerous Hittite inscriptions. It took three years before their study of those inscriptions appeared, and the academic work told little of the men behind the study and their adventures abroad.

That story had been lost to Cornell history until now.

A sesquicentennial project funded by the College of Arts and Sciences and the Department of Classics, led by history of art assistant professor Benjamin Anderson and classics professor Eric Rebillard, has uncovered compelling details about the men’s journey and discoveries; the information can be found on the College of Arts and Sciences sesquicentennial website; a symposium also is planned for the spring.

The trip’s organizer, John Robert Sitlington Sterrett, a professor of Greek at Cornell, instilled his love of travel in his most promising students. For Sterrett, the expedition of 1907-08 was the first step in an ambitious long-term plan for archaeological research in the eastern Mediterranean.

To launch this project, Sterrett selected Albert Ten Eyck Olmstead, Ph.D. 1907, and Benson Charles and Jesse Wrench, both Class of 1906. Charles and Wrench spent 1904-05 traveling in Syria and Palestine, where they rowed the Dead Sea and practiced making “squeezes,” replicas of inscriptions made by pounding wet paper onto the stone surface and letting it dry.

The expedition spent more than two weeks in Ankara, a sleepy provincial town decades away from becoming the capital of the Turkish Republic, where the Roman-era Temple of Augustus bore a monumental text relating the deified emperor’s deeds. No squeeze had ever been taken of this “Queen of Inscriptions”; the Cornell copy has been digitized and is available to scholars as part of the Grants Program for Digital Collections in Arts and Sciences.

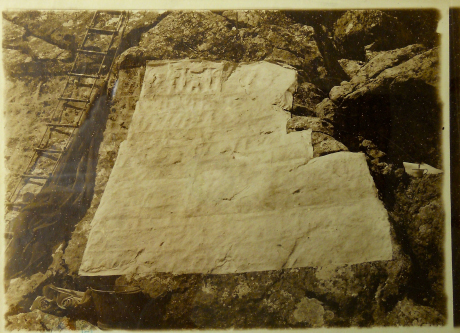

As the expedition pushed eastward and fall turned to winter, the Cornellians battled snows to cross the Taurus Mountains before the way became impassable. Nevertheless, they continued to pursue their research: a grainy photograph taken at Arslan Taş, “the lion’s stone,” shows two figures bundled against the cold, doggedly waiting for a squeeze to dry.

The expedition’s journal explains the photo, which followed a strenuous hike up a mountain “through a fall of snow so thick that one could see only a rod or two in any direction.” Once they arrived, the squeeze “froze as soon as it was on and refused to dry although we built a fire just in front. Finally darkness began to come on, and we were obliged to remove the squeeze in order to dry it over the fire. Then, in the darkness ... we descended the mountain.”

The three men planned to publish a narrative of their journey but never did. As a result they have been largely left out of the early history of American archaeology in the eastern Mediterranean. But with the help of the journals and notebooks that they left behind, Anderson and Rebillard have uncovered the distinctly Cornellian stamp they left on the tradition of the archaeological voyage: unorthodox, open-minded and unafraid of the snow.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe