Diabetes in rats treated with engineered probiotic

By Krishna Ramanujan

Imagine a pill that helps people control diabetes with the body’s own insulin.

Cornell researchers have achieved this feat in rats by engineering human lactobacilli, a common gut bacteria, to secrete a protein called Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1).

A 2003 study led by Atsushi Suzuki of the University of Tsukuba, Japan, first demonstrated that when exposed to the 37 amino acid, full-length form of GLP-1, intestinal epithelial cells that cover the guts are converted into insulin-producing cells. But until now, no one has administered full length GLP-1 into a live animal without injecting it, a method of administration that is not very effective.

In the study, published Jan. 27 in the journal Diabetes, the researchers engineered a strain of lactobacillus, a human probiotic, to secrete GLP-1, and then administered it orally to diabetic rats for 90 days. Rats with high blood glucose (called hyperglycemia, a hallmark of diabetes) that received the engineered probiotic ended up with up to 30 percent lower blood glucose levels.

The technology is being licensed by the company BioPancreate, which is working to get the therapy into production for human use.

The rat study was a proof of principle, and future work will test higher doses to see if a complete treatment can be achieved, said John March, professor of biological and environmental engineering in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences and the paper’s senior author.

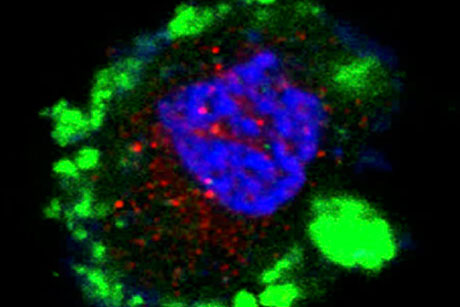

The researchers found that upper intestinal epithelial cells in diabetic rats were converted into cells that acted very much like pancreatic cells, which monitor blood glucose levels and secrete insulin as needed to balance glucose levels in healthy individuals.

“The amount of time to reduce glucose levels following a meal [in hyperglycemic rats in the study] is the same as in a normal rat … and it is matched to the amount of glucose in the blood,” just as it would be with a normal-functioning pancreas, March said. “It’s moving the center of glucose control from the pancreas to the upper intestine.”

Also, though the treatment replaces the insulin capacity in diabetic rats, the researchers found no change in blood glucose levels when administered to healthy rats. “If the rat is managing its glucose, it doesn’t need more insulin,” March said.

Human patients would likely take a pill each morning to help control their diabetes, March said.

Franklin Duan, a senior research associate, is the paper’s first author, and Joy Liu, a research technician, is a co-author; both work in March’s lab.

The study is funded by the National Institutes of Health and the Hartwell Foundation.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe