Quilts portray civil rights movement, Hollywood, family

By Linda B. Glaser

For centuries women have made quilts to express their hopes, longings and love, but Riché Richardson’s quilts also resonate with history - her own and that of the United States.

A retrospective of her work, “Portraits II: From Montgomery to Paris: The Appliqué Art Quilts of Riché Deianne Richardson,” pays tribute to the 50th anniversary of the Selma-to-Montgomery March and other anniversaries in civil rights history this year. The exhibit is on display at Troy University’s Rosa Parks Museum in Montgomery, Alabama, through March 27.

“For a long time I kept my art and my academics in separate compartments, but I’ve been astonished at how frequently the subjects I’m working on in my research are paralleled by subjects I end up making into quilts,” says Richardson, associate professor of Africana studies in the College of Arts and Sciences. “I’m able to frame similar questions in my art to ones I develop in my research, but for a different audience.”

Her Obama quilts, for example, reflect her just-completed manuscript, “Presidential Encounters: Reimagining the National Body and Black Femininity in the Transnational South,” and her research focus on gender, race and the African-American south.

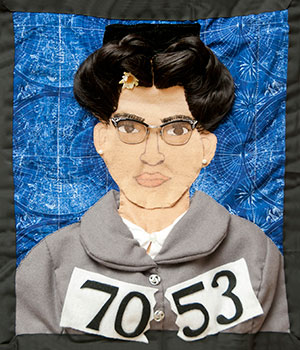

The quilts – 58 are on display – take Richardson two years on average to create, and sometimes five years or more. The level of detail makes them very time consuming; some have collar bones, eyelashes and fingernails. She uses a three-dimensional approach, with felt providing the foundation fabric, and adds a wide range of materials, including buttons, fruit, beading, jewelry and hats. Her quilts are “built” from the inside out, incorporating principles of architecture and engineering.

“I was always fascinated by soft sculpture, and that fascination has shaped my work,” she explains. “Photos don’t convey the dimensionality of the quilts. They have a coming-off-the-page effect.”

The exhibit includes light and sound effects from iPods hidden in the installations. The songs – chosen to fit the quilts, like “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend” for the Marilyn Monroe quilt – bounce around the gallery room.

“It creates a unique experience for our audience,” says Richardson. “It’s especially rare to do something like this with quilts. We’ve pushed the limit.”

Richardson has always worked in series, and the museum displays them grouped together: the Africa Quilt Series, the Hollywood Series and what she calls the “heart” of the exhibit, the Family Series.

“I reimagine classic family photos,” explains Richardson. “Some of the photos were taken during the Jim Crow era but show the beauty and dignity of what being black at that time meant.”

The exhibit is dedicated to her grandfather, Joe Richardson, and to her grandmother, Emma Lou Jenkins Richardson, who recently passed away.

The Debutante Triple Quilt in the Family Series grounds the exhibit, says Richardson, and spotlights a custom still very alive in Southern culture. She notes that in the African-American context, debutante experiences are linked to education and scholarships; debutante Richardson received several such scholarships.

While Richardson hopes visitors will enjoy the exhibit, her goal is that it also resonates at deep levels. “The Family Series will help people to reach within and think about their own family, their ancestors, the people who’ve helped them become who they are, and celebrate what their history looks like in the context of broader history,” she says.

“The quilts show the diversity of people and highlight the beauty of the human spectrum. I want visitors to the exhibit to think about what art means, to reach within and rediscover or reinforce the artist within themselves.”

Linda B. Glaser is a writer for the College of Arts and Sciences.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe