Hunting for hidden life on worlds orbiting old, red stars

By Blaine Friedlander

Searching vast cosmic communities like real estate agents rifling through listings, Cornell astronomers now hunt through time and space for habitable exoplanets – planets beyond our own solar system – looking at planets flourishing in old star, red giant neighborhoods.

Astronomers search for these promising worlds by looking for the “habitable zone,” the region around a star in which water on a planet’s surface is liquid and signs of life can be remotely detected by telescopes.

“When a star ages and brightens, the habitable zone moves outward and you’re basically giving a second wind to a planetary system,” said Ramses M. Ramirez, research associate at Cornell’s Carl Sagan Institute and lead author of the study. “Currently objects in these outer regions are frozen in our own solar system, like Europa and Enceladus – moons orbiting Jupiter and Saturn.”

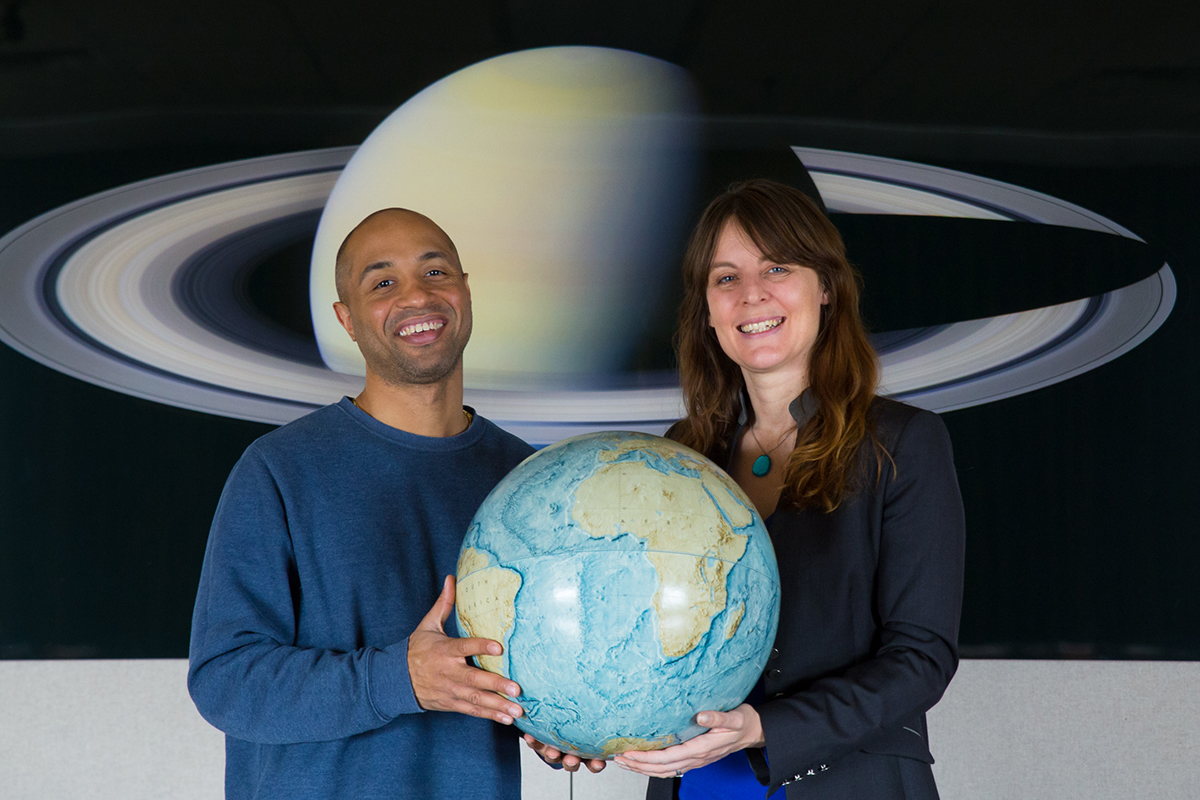

In their work, Ramirez and Lisa Kaltenegger, associate professor of astronomy and director of the Sagan Institute, have modeled the locations of the habitable zones for aging stars and how long planets can stay in it. Their research, “Habitable Zones of Post-Main Sequence Stars,” will be published May 16 in the Astrophysical Journal.

“Long after our own plain yellow sun expands to become a red giant star and turns Earth into a sizzling hot wasteland, there are still regions in our solar system – and other solar systems as well – where life might thrive,” Kaltenegger said.

All throughout the universe there are stars in varying phases and ages. The oldest detected Kepler planets (exoplanets found using NASA’s Kepler telescope) are about 11 billion years old, and the exoplanetary diversity suggests that around other stars, such initially frozen worlds could be the size of Earth and could provide habitable conditions once the star becomes older. Astronomers usually looked at middle-aged stars like our sun, but to find habitable worlds, one needs to look around stars of all ages, Kaltenegger said.

Dependent upon the mass (weight) of the original star, planets and their moons loiter in this red giant habitable zone up to 9 billion years. Earth, for example, has been in our sun’s habitable zone so far for about 4.5 billion years, and it has teemed with changing iterations of life. However, in a few billion years our sun will become a red giant, engulfing Mercury and Venus, turning Earth and Mars into sizzling rocky planets, and warming distant worlds like Jupiter, Saturn and Neptune – and their moons – in a newly established red giant habitable zone.

“For stars that are like our sun, but older, such thawed planets could stay warm up to half a billion years. That’s no small amount of time,” said Ramirez.

Said Kaltenegger: “In the far future, such worlds could become habitable around small red suns for billions of years, maybe even starting life, just like Earth. That makes me very optimistic for the chances for life in the long run.”

This research was supported by the Simons Foundation and by the Carl Sagan Institute.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe