Pulitzer Prize-winning alum pens book about adventures in love and work

By Kathy Hovis

One of the things that Jeffrey Gettleman ’94 appreciated about being a Cornell student was the opportunity to reinvent himself anytime he felt he needed to.

“I was the frat guy playing lacrosse, then my interests changed and I got very into the arts scene and photography, then I spent a lot of time at the Africana studies center,” says Gettleman. “Cornell allowed me to metamorphosize into different people, to keep finding new corners of campus life.”

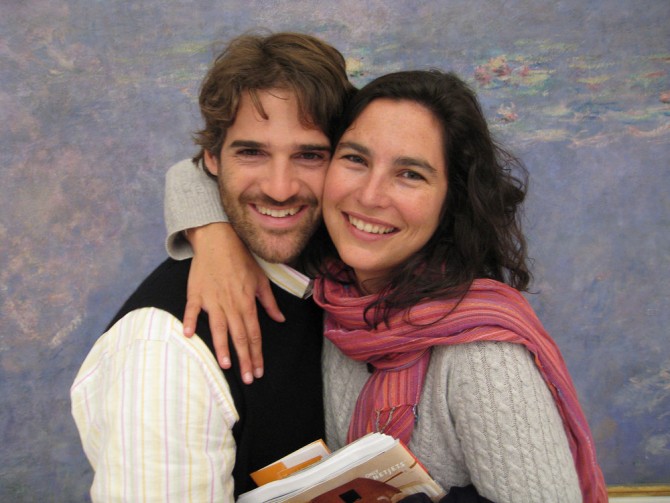

Gettleman is undergoing a major transition again, this time leaving his job after 11 years as the East Africa bureau chief for The New York Times and heading to India with his wife, attorney Courtenay Morris ’94, and their two sons to work as the Times’ India bureau chief. He’s also celebrating the release of his new book, “Love, Africa,” which chronicles his career in journalism, but also explores his time at Cornell, his romance with Morris and their adventures together.

“I wanted to write about growing up and making mistakes,” he says. “The final product is as much about growing up and coming of age as it is about journalism and Africa.”

Gettleman writes in the book about the challenges of being a journalist in sometimes heart-wrenching situations. “I felt like a part of my personality was excised when I was writing a newspaper article,” he says. “We have to be objective and neutral and remote from the material, but I was covering a lot of very interesting experiences and I wanted to share them in a personal way.”

Gettleman and Morris met at Cornell, where he studied philosophy and she studied Russian literature. After graduation, Gettleman spent two years at Oxford on a Marshall scholarship and completed a master’s degree in anthropology, and Morris earned her law degree.

Gettleman says he fell into journalism, prompted in part by the memory of a discussion with Lamar Herrin, Cornell professor emeritus of English, who encouraged Gettleman to consider the idea during a creative writing class.

“I was the archetypal liberal arts student with a million interests,” he recalls. “I studied Swahili, Indonesian, photography, philosophy.” At Cornell, he was a walk-on on the lacrosse team, was president of the Cornell Civil Liberties Union, joined a fraternity, was a member of Cornell Students for Racial Understanding, and took photos for The Cornell Daily Sun.

After his first job in St. Petersburg, Florida, and following several other newspaper jobs and moves, Morris and Gettleman married and ended up working together for The New York Times in Africa – Gettleman as a journalist and Morris as a videographer.

Winding up in Africa wasn’t a fluke, but part of a plan Gettleman had been creating since he traveled there during the summer after his freshman year on a student-led trip to aid refugees.

“East Africa is a really beautiful, warm part of the world,” he says. “There’s a strong spirit between people, a sense of humanity. People stay more closely connected to each other.”

Gettleman says his job as a journalist there was to shed light on a part of the world that Times readers don’t usually think about – and to make them care.

“We’re in the empathy generation business,” he explains. “I believe in this idea that if you have a lot, if you come from a world that’s safe and comfortable, you should be actively thinking of a way to help people who don’t have lives like that.”

While the location in East Africa was warm and welcoming, his job was anything but comfortable. He and Morris were kidnapped by government soldiers in Ethiopia, and he was often surrounded by soldiers with machine guns.

“There’s a sense of uncertainty in a lot of this work. You don’t know what you’re getting into,” he says. “There were times when I really felt like I was going to die. It would cross my mind to question ‘Am I going to come back from this or are there guys going to whisk me away?’ But you use your intuition and you try to read people constantly.”

Gettleman’s coverage of famine in Sudan, pirates in Somalia and other conflicts raging in 2011 in East Africa earned him the Pulitzer Prize in 2012 for international reporting.

“There’s a lot of luck that goes into that,” Gettleman says about the Pulitzer, adding that few journalists were invested in covering Africa at that time. “I was well positioned, working in those countries. I had the sources. I had the networks. I knew how to get to these places.”

Gettleman says his recent move to India will give him the chance to share with readers the wonder of discovering a new country.

“It’s a very complicated, colorful and dynamic place that I have to figure out,” he says.

“I’ll be writing more stories about social justice, religion, changing culture and economic development and fewer about natural disasters and conflicts.

“At this point in my life, if I was never on another battlefield or surrounded by people in a field of guns, it would be OK with me.”

Kathy Hovis is a writer for the College of Arts and Sciences.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe