Metastatic breast cancer affects bone mineral before spreading

By Tom Fleischman

When breast cancer metastasizes, or spreads, one of its most likely destinations is bone. In fact, four in five metastatic breast cancer patients will develop bone lesions, according to research published by the National Institutes of Health.

Most research studies have focused on the cellular and molecular mechanisms involved in cancer metastasis, but little is known about how the physical properties of bone are altered by cancer.

An international collaboration led by Claudia Fischbach-Teschl – associate professor in the Meinig School of Biomedical Engineering and co-director of the Cornell Center on the Physics of Cancer Metabolism – reports that not only does the cancer favor a certain state of bone mineral, but that breast cancer tumors actually remotely enhance that favorable state – “talk,” in effect, with the region of choice – before metastasizing there.

The group’s paper, “Multiscale Characterization of the Mineral Phase at Skeletal Sites of Breast Cancer Metastasis,” published online Sept. 18 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Collaborators included Lara Estroff, associate professor in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering, and Peter Fratzl, director of the Biomaterials Department at the Max Planck Institute for Colloids and Interfaces in Potsdam, Germany.

First author was Frank He, doctoral student in biomedical engineering and a member of the Fischbach Lab.

Even before breast cancer cells spread to the skeleton, they interact with bone cells to facilitate later tumor growth at these sites. This region of interest for disseminated cancer cells is known as the pre-metastatic niche.

“Cancer is not only about the cancer cells themselves, but also about in which context they actually develop,” Fischbach-Teschl said.

At the same time this remote cellular interaction is taking place, the cancer cells are disrupting the bone’s natural remodeling, a constant process in which old tissue is shed and new tissue forms. Metastasis in the bone triggers a vicious cycle: Cancer cells migrate to a region that’s suited for their growth, and their presence degrades the region, making it even more suited to tumor growth.

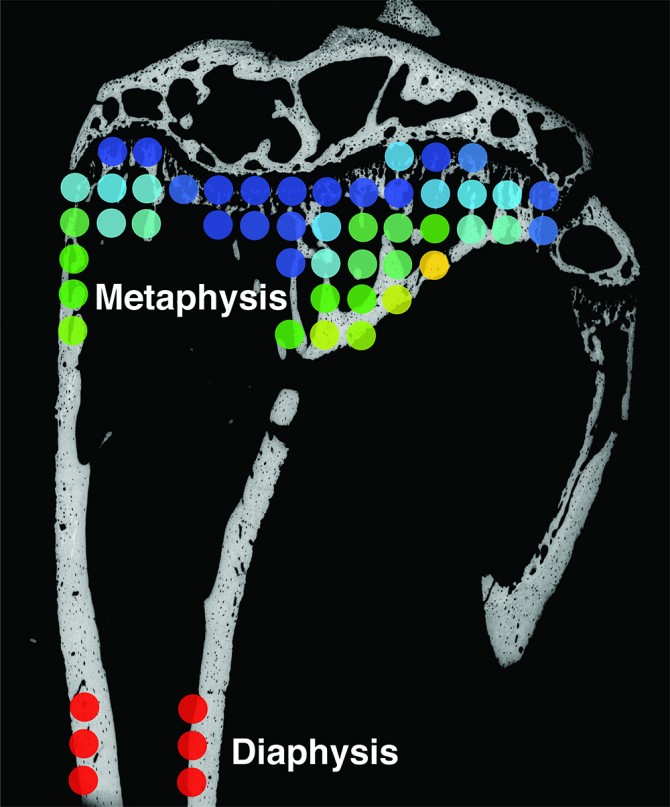

Her team’s study involved mouse experiments to model how tumor cells interact with bone in patients. It is well understood that in mice, secondary tumors are likely to form in the tibia – specifically the area of bone near the knee joint, known as the metaphysis.

“This makes sense,” Fischbach-Teschl said, “because the metaphysis is characterized by high turnover rates, so there’s a lot of activity going on there.”

The group focused on nanocrystals of the mineral hydroxyapatite (HA), which is a key component of the bone’s unique structural and mechanical properties and likely to influence metastasis. They found that HA crystals in that region of the tibia are typically smaller and less mature than in the cortical bone in the shaft of the tibia, known as the diaphysis. This finding is important as Fischbach-Teschl and Estroff showed previously that breast cancer cells can better adhere and proliferate on smaller, less-perfect HA crystals.

Analysis of the metaphyseal bone after breast cancer cell injection into the bloodstream, a procedure that will produce tumors in bone, confirmed that metastatic breast tumors degrade bone. Additionally, this analysis showed that the HA crystals in the remaining bone were even less mature than before the cancer arrived.

The surprising result came after breast cancer cells were injected directly into mammary tissue. Not only did the cells produce a localized tumor, but they affected the metaphysis – even before the formation of metastasis.

“The tumors were just in the mammary fat pad tissue,” Fischbach-Teschl said, “and even prior to the tumors going [to the tibia] and forming the colony, we were already seeing changes in the bone mineral nanostructure toward crystals that we think will support metastasis formation.”

Gaining a greater understanding of the pre-metastatic niche, not only from a biological, but also a materials science perspective, could help inform therapeutic decisions in the future, Fischbach-Teschl said.

“The goal now is to really understand why these changes are happening,” she said. “Why and how do tumor cells change these properties in bone, prior to the formation of metastasis, and how is that then functionally relevant to seeding a new tumor?”

Doctoral student Aaron Chiou, from the Fischbach Lab, also contributed to this work, which was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the National Cancer Institute and the National Science Foundation, as well as Fischbach-Teschl’s 2013 Alexander von Humboldt Foundation fellowship.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe