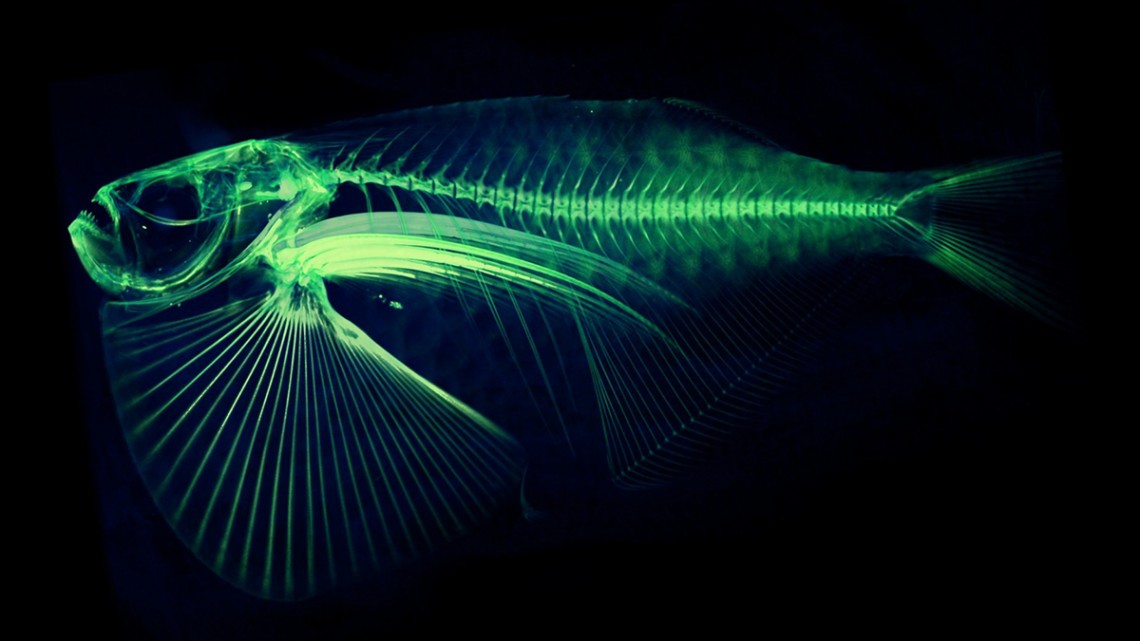

Internal structure of a spotfin hatchetfish, Thoracocorax stellatus.

3-D scanning project of 20,000 animals makes details available worldwide

By Krishna Ramanujan

What began as a Twitter joke between two researchers has turned into a four-year, $2.5 million National Science Foundation grant to take 3-D digital scans of 20,000 museum vertebrate specimens and make them available to everyone online.

Cornell’s Museum of Vertebrates, with 1.3 million fish specimens, 27,000 reptiles and amphibians (called herps), and 57,000 bird and 23,000 mammal specimens, is one of 16 institutions involved and promises to feature prominently in the project.

Last year, Adam Summers, a University of Washington biomechanist, joked he wanted to “scan all fishes” after computer tomography scans of fish he posted on Twitter received some attention. David Blackburn, curator of herpetology at the Florida Museum of Natural History in Gainesville, and principal investigator of the grant, tweeted back that he wanted to “scan all frogs.”

The grant, announced this month, will fund oVert (Open Exploration of Vertebrate Diversity in 3-D), a project that aims to scan samples representing 80 percent of all recognized genera of vertebrates. Additional scans will bolster certain genera, especially those belonging to model systems that are heavily used in research, such as cichlids from African Rift lakes, used for studying evolution, or zebrafish, used by neuro-scientists.

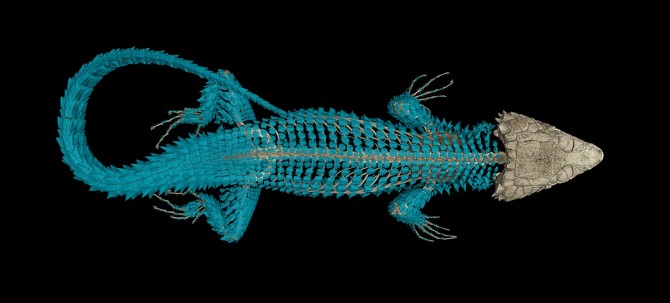

About 1,000 of the 20,000 specimens – which have been stored and housed in preserving fluid – will be scanned for soft tissues, meaning they will be treated with an iodine stain to highlight soft tissue structures.

The type species – an individual that serves as the archetype for a species – for each genus will be represented when possible, and the details concerning which species will be represented and what each institution will contribute will be discussed at oVert’s first meeting in November.

The open source collection, housed in a digital depository called MorphoSource, will be available to researchers in such fields as anatomy, evolution and developmental biology, as well as for educational and outreach purposes.

While digitization efforts will never replace the value of specimens on museum shelves, they do offer access to people who may not have such resources nearby.

“In an open-source era, as soon as its digitized, that information is now immediately available to anyone in the world,” said Casey Dillman, curator of fishes, amphibians and reptiles at the Cornell University Museum of Vertebrates.

In this way, a researcher in another country who wants to compare the skull of a local minnow to a North American minnow may now simply go online to do so. “It takes the physical specimen off the shelf and puts it in everyone’s hands,” Dillman added.

Cornell’s vertebrate museum’s fishes collection is particularly strong with great diversity in North American fishes, and minnows in particular. Beginning in the 1940’s and continuing into the 1970’s the fish collection was greatly expanded thanks to collections made by renowned Cornell ichthyologist Edward Raney and his students.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe