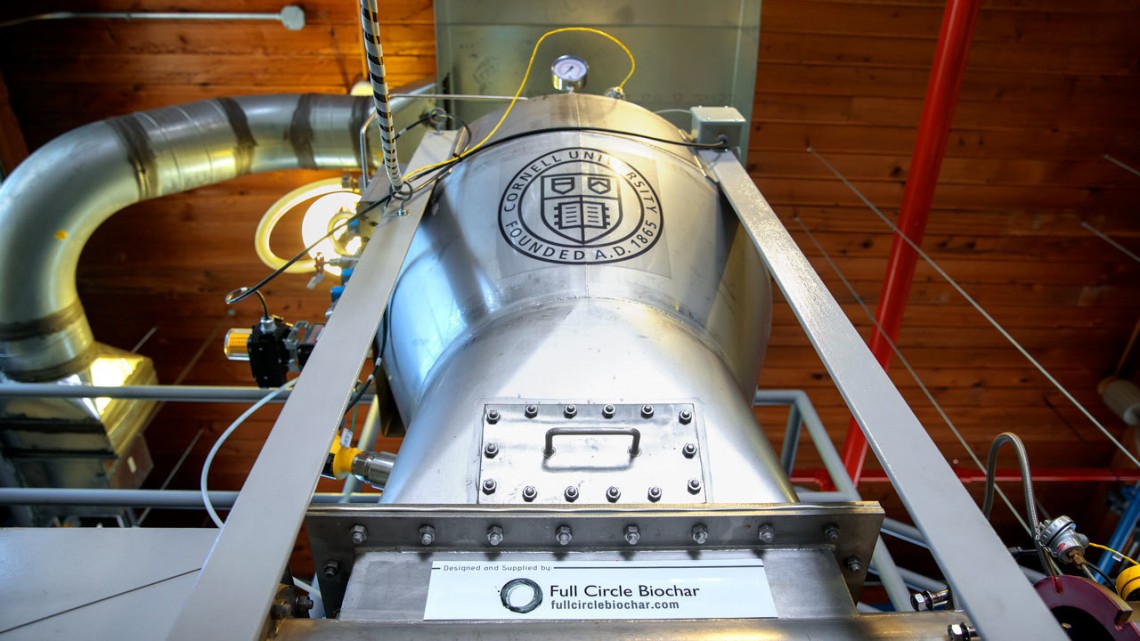

Cornell’s new pyrolysis kiln opened May 24 at a celebration in the Leland Laboratory on campus.

Trash to treasure: Cornell’s pyrolysis kiln opens May 24

By Blaine Friedlander

Waste could soon become a precious gem as Cornell’s new pyrolysis kiln – the largest of its kind at a U.S. university – opened May 24 at a celebration in the Leland Laboratory on campus. Scientists and engineers will investigate the potential for energy production from the gases, make new biomaterials and create Earth-friendly biochar.

“We’re excited to start a new chapter in interdisciplinary research leveraged by this unique facility. It connects bio-energy with soil science, agriculture, energy storage and waste management,” Johannes Lehmann, professor of soil science and a fellow at Cornell’s Atkinson Center for a Sustainable Future, said at the opening.

“This pyrolysis unit is one of the most sophisticated slow-pyrolysis units in any institution worldwide,” Lehmann said. “It has unique capabilities that allow high versatility and continuous monitoring. I would call it the Rolls Royce of pyrolysis units.”

The kiln was designed and built by Full Circle Biochar, a California-based company eager to demonstrate the economic feasibility of eco-friendly, biomass-based materials. Full Circle Biochar is working in close collaboration with Cornell on biochar research and development.

Cornell’s pyrolysis kiln project began in 2010 when philanthropist Yossie Hollander and his family made a $5 million gift to the Cornell Center for a Sustainable Future – predecessor to the Atkinson Center – to advance biofuel technology for developing countries.

The new kiln is classified as a demonstration unit and it is larger than regular, small-sample university kilns. “The results are much more commercially representative. You can translate these results into larger units,” said kiln designer Cordner Peacocke, owner of C.A.R.E. Ltd., a bioenergy and waste to energy engineering firm in Northern Ireland.

The designer said Cornell’s new kiln is flexible.

“You can add more heat at the start, rather than at the end to improve drying, if required, as the greatest thermal demand for pyrolysis is at the start. Or you can vary the temperature along the kiln and have higher temperatures at the end if you want to anneal your char and reduce volatiles,” Peacocke said. “You can tilt the kiln to vary the residence time of the solids. You can feed various particle sizes and shapes. From a research perspective, there are several parameters you can easily change and the final char product would be commercially applicable.”

Materials can be fed into the kiln continuously – for up to four hours before a hopper refill is needed – and it is very controllable. The kiln can handle up to 120 pounds of wood chip an hour and reach up to 600 degrees Celsius.

“This kiln is small enough to be flexible to meet the needs of product development, but big enough to be relevant to scale up research,” said John Gaunt, adjunct associate professor in plant sciences and a partner in the project.

“One of the fascinating things about the equipment is the product intersects with our life in so many different ways,” said Gaunt, also an Atkinson Center fellow. “There are so many points of intersection – everything from agriculture to energy to construction materials to animal feed. We can produce samples from our research that we can scale into processes for a commercial operation. It’s really quite amazing.”

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe