‘Paths to Peace’ explores legacy of antiwar campaigner

By Jonathan Miller

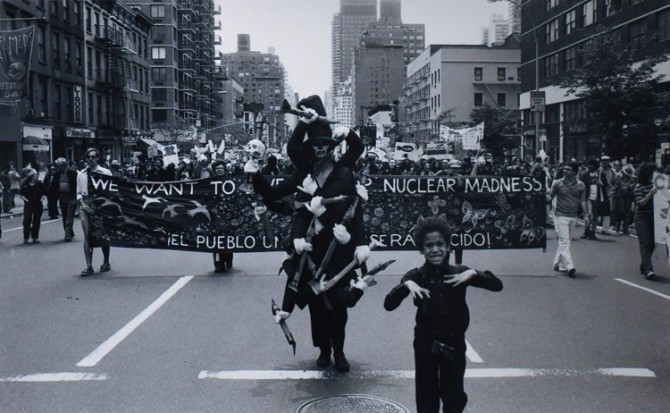

On June 12, 1982, an estimated one million people marched through the streets of New York City to protest the nuclear arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union. They had a simple proposition: immediately freeze the development and deployment of nuclear weapons. Then, they argued, we can begin the hard work of eliminating them altogether.

It was the largest political demonstration in U.S. history. The woman who led it – and who came up with the freeze plan in the first place – was a strong-willed, detail-oriented military analyst named Randall “Randy” Forsberg.

“Until the arms race stops,” she told the crowd, “until we have a world with peace and justice, we will not go home and be quiet. We will go home and organize.”

A series of on-campus events and exhibits will explore Forsberg’s legacy at a time of heightened tensions about nuclear security and the threat of war. “Paths to Peace” includes film screenings, art exhibits, a seminar, a panel discussion, a book launch and the opening of an archive of records from a think tank Forsberg founded.

Events begin Aug. 30 and continue through Sept. 14, when a group of peace and conflict studies scholars from around the country will meet for a workshop examining Forsberg’s work. The series is organized by the Judith Reppy Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies, Mario Einaudi Center for International Studies, Cornell University Library, Cornell Cinema, the Big Red Barn and Durland Alternatives Library.

“With the concern over the nuclear issue in North Korea and Iran, it seemed the right time to do this,” said Matthew Evangelista, the President White Professor of Government and a former student and colleague of Forsberg. “The nuclear freeze campaign did not end the arms race, but it did capture the public mood of anxiety about the threat of nuclear war and propose a viable solution. We could use something like that now.”

Forsberg (1943–2007) studied English at Columbia University, then worked as an analyst at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute in the 1960s and 1970s. After starting graduate school at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, she founded the Nuclear Weapons Freeze Campaign and the Institute for Defense and Disarmament Studies (IDDS).

By the early 1980s, opinion polls showed that more than 70 percent of Americans supported her nuclear freeze proposal. Legislatures in 23 states endorsed the plan. It was incorporated into the 1984 Democratic Party presidential platform. Although interest declined after that, Forsberg remained influential in the peace and disarmament movements until she died of cancer at age 64.

Best known for her activism, Forsberg also was an important thinker, Evangelista said. “Over time she developed a sophisticated theory of social change that envisioned an eventual end to war as an institution,” he said.

She explored this in her doctoral thesis, “Toward a Theory of Peace: The Role of Moral Beliefs,” completed when she was in her 50s. The Einaudi Center has posted an edited version of the thesis on its e-book platform prior to its formal publication by Cornell University Press on the center’s imprint, Cornell Global Perspectives.

The thesis describes how public attitudes toward cannibalism, human sacrifice, slavery and other forms of “socially sanctioned violence” have changed over time, and suggests that the same processes that made those practices unacceptable may eventually lead to the rejection of war. It also tracks the relationship between the rise in democracy and the control of violence.

The book includes an introduction by Evangelista and Boston University political scientist Neta C. Crawford, another long-time colleague and former intern at Forsberg’s institute. “Randy’s approach to social change included increasing the capacity for the public to understand and challenge nuclear weapons policy,” Crawford said. “She helped build the freeze and peace movements by providing information and analysis about nuclear weapons and war.”

Forsberg had strong connections with scholars and activists at Cornell. Judith Reppy (science and technology studies, emerita) was chair of the IDDS board at the time of Forsberg’s death. She arranged for the transfer of the institute’s correspondence, publications, audio and video recordings and other materials to Cornell University Library’s Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections.

Evangelista, whose research explores ethical and legal issues around the conduct of war, studied and worked with Forsberg as an undergraduate at Harvard University. He came to Cornell to pursue his Ph.D. at the suggestion of Forsberg and Reppy, then director of the Peace Studies Program later renamed in her honor in 2010. Evangelista joined the Cornell faculty in 1996 and has served as director of the program on several occasions.

Jonathan Miller is associate director for communications at the Einaudi Center.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe