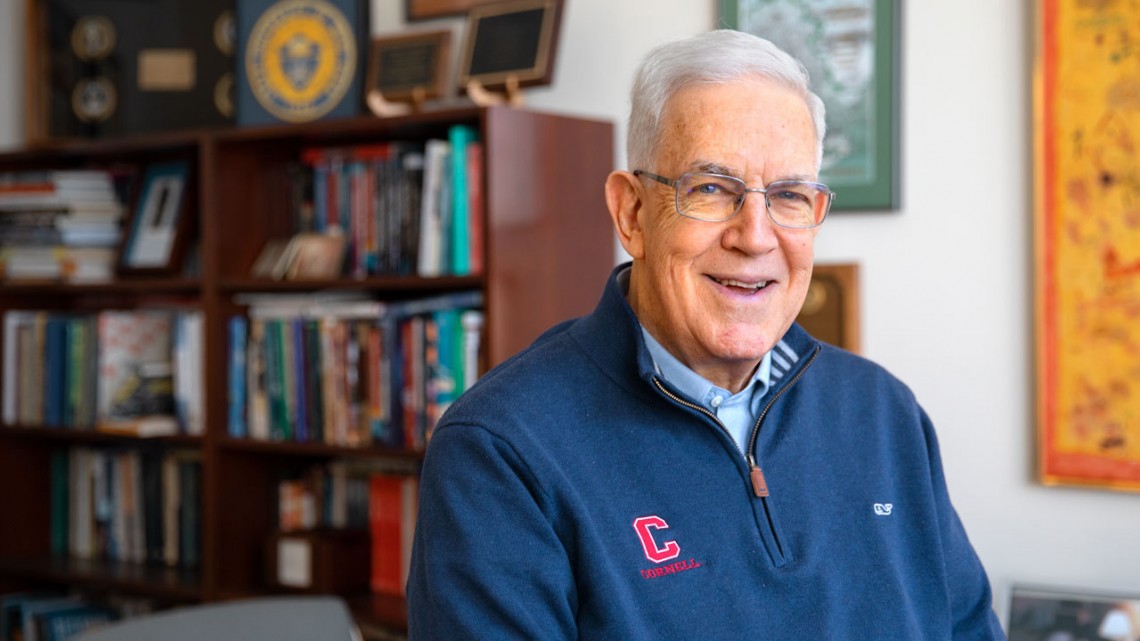

Ron Ehrenberg, the Irving M. Ives Professor of Industrial and Labor Relations and Economics, in his office in Ives Hall.

Facing illness, Ehrenberg revisits ‘Last Lecture’

By Nancy Doolittle

Ron Ehrenberg’s accomplishments are many – and so are the adversities he and his wife, Randy, have faced.

In a “Last Lecture” he wrote 15 years ago for the Cornell chapter of the Mortar Board honor society, Ehrenberg summarized what he learned during his oldest son Eric’s first 14 years of his battle against cancer. Those lessons have stood the test of time; now, as Ehrenberg faces advanced kidney disease, he reflects on their relevance to his current life and the challenges ahead.

Ehrenberg is well-respected as a scholar, teacher and administrator. In 1985, he was named Cornell’s first Irving M. Ives Professor of Industrial and Labor Relations and Economics. He established and became the first director of the Cornell Higher Education Research Institute in July 1998, and is widely known for his published work in economics. He served as Cornell’s vice president for academic programs, planning and budgeting for three years, and was a member of the university’s board of trustees for four. He recently stepped down after serving seven years on the State University of New York Board of Trustees.

Named a Stephen H. Weiss Presidential Fellow in 2005 for the quality of his undergraduate teaching, Ehrenberg also has chaired the doctoral committees of more than 50 Ph.D.s. He has been awarded lifetime achievement awards from two professional associations and honorary doctorate degrees from two universities. In 2014, the ILR School honored him by creating a professorship named for him.

In 1990, in the midst of Ehrenberg’s most productive years, his son Eric – then a junior at Cornell – was diagnosed with brain cancer and told that he might have less than a year to live. After surgeries, chemotherapy and radiation therapy, Eric stabilized and graduated from Cornell and then Georgetown Law School. In 2004, his cancer returned and he underwent more surgeries: He died from complications four years later, leaving behind a wife, daughter and son born three months after his death.

Ehrenberg’s “Last Lecture” was written before his son’s relapse. Ehrenberg updated it for a Cornell alumni reunion address in 2009, and it was folded into a compilation of his reflective pieces in a tribute to his legacy, celebrated in 2017.

The Ehrenbergs are now facing what feels like instant replay: Last fall, their younger son, Jason ’96, was diagnosed with a similar type of tumor as his older brother, and the chemotherapy he underwent also led to a heart attack and a stroke.

But Ehrenberg draws strength from the messages he took from his first son’s experiences. Eric lived 18 years from his initial diagnosis, far exceeding his doctors’ expectations, Ehrenberg said, so he knows that “probabilities that doctors give you when you are suffering from an illness are only probabilities. … You should not lose hope that you will be a winner.”

At the same time, Ehrenberg knows, “life is all about changing expectations.” After Eric’s death, Randy Ehrenberg retired as a superintendent of schools in the Albany area to move back to Ithaca. She now serves in leadership roles with various nonprofit organizations in the area. She and Ehrenberg have put long-range travel plans on hold because of his illness.

Another message from his last lecture that Ehrenberg has accepted: No one ever said that life would be fair. Nearly 18 years ago, ILR colleague Robert Stern died at age 51 from complications from childhood diabetes. “Some people, like Bob Stern and my son, suffer serious losses at early ages, while others seem to get free passes throughout most of their lives,” Ehrenberg wrote.

Stern had visited Eric early in his treatment and advised him not to compare himself to what he was in the past or to people around him. Ehrenberg tries to follow this advice himself.

However, he admits, “I have gone through many of the stages of grief with [my kidney disease], but I am still working on seeing dialysis as life-saving rather than life-limiting.”

To counter those feelings, Ehrenberg reminds himself and advises others to “simply ask what can you do to make yourself and the people you care about feel as fulfilled and happy as possible.” His energies are focused on finding a kidney donor, teaching undergraduates and supporting his wife in her new endeavors. Among their greatest concerns, should Ehrenberg not receive a kidney soon, dialysis will limit his ability to visit, without much advanced preparation, their four grandchildren in Washington, D.C.

“Life is with people, and having a community that you can turn to in times of need and contribute to throughout your life is very important,” Ehrenberg said.

For the immediate future, that means spending spring break in Washington, D.C., and continuing to teach at ILR. “The support I have gotten from ILR and the university as a whole has been extraordinary,” he said.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe