The Canada warbler is one of 117 bird species whose habitat across the Western Hemisphere would be protected under the conservation plan.

Scientists propose bird conservation plan based on eBird data

By Gustave Axelson

A blueprint for conserving enough habitat to protect the populations of almost one-third of the warblers, orioles, tanagers and other birds that migrate among the Americas throughout the year is detailed in research published April 15 in Nature Communications.

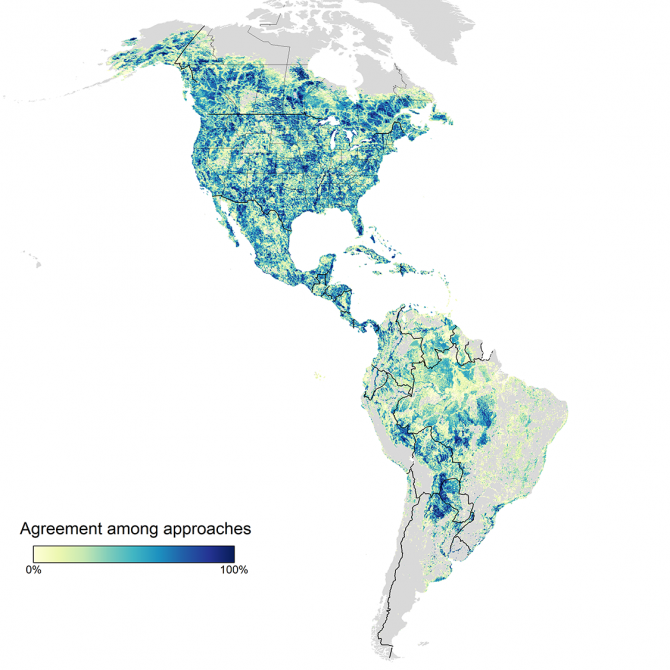

An international team of scientists used eBird, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s global citizen science database, to calculate how to sufficiently conserve habitat across the Western Hemisphere for all the habitats these birds use throughout their annual cycle of breeding, migration and overwintering. The study provides planners with guidance on the locations and amounts of land that must be conserved for 30% of the global populations for each of 117 bird species that migrate to the Neotropics (Central and South America, the Caribbean and southern North America).

More than one-third of Neotropical migratory birds are suffering population declines, yet a 2015 global assessment found that only 9% of migratory bird species have adequate habitat protection across their yearly ranges to protect their populations. Conservation of migratory birds has historically been difficult, partly because they require habitat across continents and conservation efforts have been challenged by limited knowledge of their abundance and distribution over their vast ranges and throughout the year.

“We are excited to be the first to use a data-driven (eBird) approach that identifies the most critical places for bird conservation across breeding, overwintering and migratory stopover areas throughout the Western Hemisphere,” said lead author Richard Schuster, a postdoctoral fellow at Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario. “In doing so, we provide guidance on where, when and what type of habitat should be conserved to sustain populations. This is a vital step if conservationists are to make the best use of limited resources and address the most critical problems at a hemispheric scale.”

The team’s analysis found that conservation strategies were most efficient when they incorporated working lands, such as agriculture or forestry, rather than exclusively focusing on areas with limited human impacts (i.e., intact or undisturbed landscapes). The importance of shared-use or working landscapes to migratory birds underscores how strategic conservation can accommodate both human livelihoods and biodiversity. The research also found that efficiency was greatest – requiring 56% less land area – when planning across the entire year in full, rather than separately by week.

“This study illustrates how globally crowdsourced data can facilitate strategic planning to achieve the best return on conservation investments,” said co-author Amanda Rodewald, senior conservation science director at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. “No other data source could have achieved anything close to this level of detail and efficiency in spatial planning over such a vast area.”

“Efforts to conserve migratory species have traditionally focused on single species and emphasized breeding grounds. Our results show that planning for multiple species across the entire year represents a far more efficient approach to land use planning,” said co-author Scott Wilson, research scientist with Environment and Climate Change Canada, a Canadian government organization.

“Prioritizing sites in which to invest our conservation dollars will dramatically improve our returns on the roughly $1 billion spent annually on the conservation of birds by government and nonprofit organizations, often in the absence of spatially explicit information on year-round abundance or geographical representation,” said Peter Arcese, co-author and chair of applied conservation biology at the University of British Columbia.

This work was funded by The Leon Levy Foundation, The Wolf Creek Charitable Foundation, NASA, a Microsoft Azure Research Award and the National Science Foundation.

Gustave Axelson is editorial director at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe