Professor publishes Placentius’ pugnacious pig poem

By Linda B. Glaser

“Pugna Porcorum” (“The Pig War”) might just be the strangest poem in all of Latin literature.

Each word of the satirical, pun-filled, 248-verse epic, first published in 1530, begins with the letter “p.” The poem describes a conflict between corrupt porcine creatures who are “hogging” all the privileges and the piglets who want their share. Said conflict soon descends into outright war.

In the first translation of the poem, Michael Fontaine, professor of classics in the College of Arts and Sciences, offers a critical reading that explores the poem’s possible influence on George Orwell’s “Animal Farm.” He also establishes how the author’s use of a pseudonym sowed confusion among his 16th-century contemporaries and later scholars.

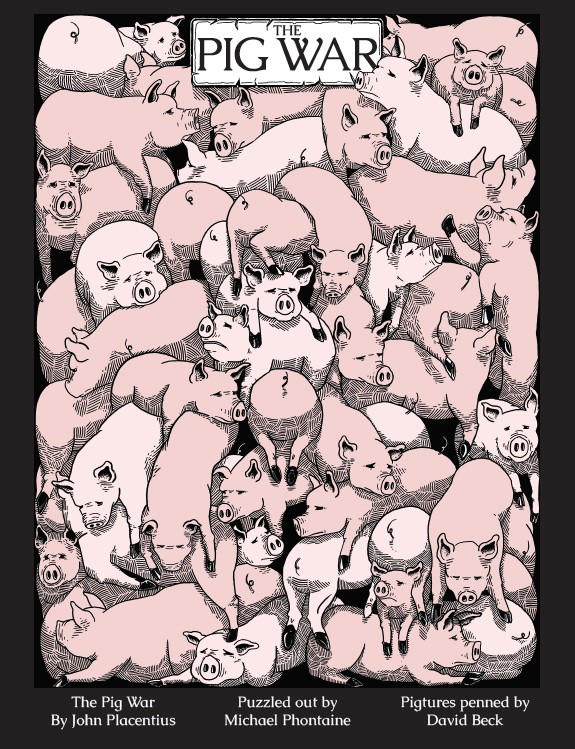

Fontaine describes the “trifecta” of the poem – the alliteration, the puns and pigs-as-humans – as “totally infectious and irresistible.” Fontaine – who calls himself “Phontaine” on the title page – is clearly having fun with his translation, and the volume includes clever original illustrations by David Beck that bring the story to life.

The project grew as a companion piece to Fontaine’s forthcoming translation of “How to Drink,” in an effort to disprove an allegation that the same author wrote both Latin works. The confusion arose because the byline for “The Pig War” is Publius Porcius Poeta rather than the author’s real name, John Placentius.

When the poem was pirated and reprinted in another city, Philip Melanchthon, an intellectual leader of the Reformation, was accused of having written it. Melanchthon denied authorship and pointed the finger instead at “How to Drink” author Vincent Obsopoeus. The debate continued for several centuries until Placentius was finally confirmed, by Fontaine, as the author.

French and English literary journals rediscovered “The Pig War” in the late 19th century. Fontaine believes the poem may have caught Orwell’s eye and influenced his famous work.

“[The genius of ‘Animal Farm’] lay in using pigs to allegorize human corruption, conflict and revolutionary violence in a simple and transparent way,” just as “The Pig War” did, Fontaine wrote. He points to numerous similarities between Orwell’s work and the Latin poem.

“Both are satirical mini-epics,” Fontaine wrote, “and their plots follow similar lines: the quick rebellion in ‘Animal Farm’ Chapter 2; the pigs’ consolidation of privileges in Chapter 3; the second battle of Chapter 4; the pigs’ competitive speechmaking, in-fighting, violence and increasing corruption in Chapters 5 and 6; and even Chapter 7’s framing of the pig Snowball as a dastardly traitor.

“Equally impressive,” Fontaine wrote, “are a number of details common to both – the pigs’ use of written proclamations, the victory parade, even cannibalism.”

In Placentius’ “spectacularly impressive” use of Latin words that bear two opposite meanings, Fontaine wrote, “we discern the unmistakable roots of Newspeak.” But the “most startling similarity,” according to Fontaine, is “the text’s emphasis on ‘the corruption of equality’ among the pigs.”

In his “Aftermath” to the book, which is published by Paideia Institute Press, Fontaine wrote: “The envy of privileges, preferments and perquisites is universal; we all feel it. So is the tendency to hog them; we all do. We always will. That is the story of ‘The Pig War.’”

But in the spirit of the book’s topsy-turvy legacy, Fontaine turns that cynical condemnation of human greed on its head. Fontaine is donating all royalties from sales of the book to Paideia Institute student scholarships, in order to increase diversity, access and inclusion at the institute.

Or, as Fontaine put it on his web page: “Potential patrons! ’Pon purchase, publication proceeds – pennies, pounds, pesos – pay pupils’ programs, provisions, pilgrimages, produce perks, promote participation, push progress!”

Linda B. Glaser is news and media relations manager for the College of Arts and Sciences.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe