Researchers show how to measure conductance of carbon nanotubes, one by one

By Anne Ju

A single batch of carbon nanotubes -- molecular carbon cylinders that may one day revolutionize electronics engineering -- often includes more than 100 types of tubes, each with different optical and electrical properties. Individual electrical measurements of the molecules typically require such slow and expensive methods as electron-beam lithography.

But now a team of Cornell researchers has invented an efficient, inexpensive method to electrically characterize individual carbon nanotubes, even when they are of slightly different shapes and sizes and are networked together.

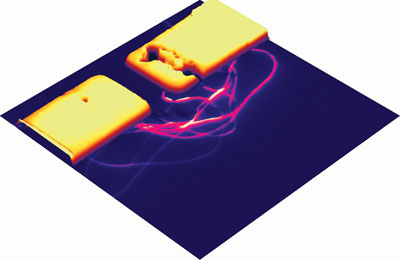

Led by Jiwoong Park, Cornell assistant professor of chemistry and chemical biology, the group has demonstrated how to measure electrical conductance of both a single nanotube, and up to 150 of them arrayed together, using a single set of electrodes and the heat from a laser. The method is called photothermal current microscopy and could be a major step toward full manipulation of carbon nanotubes in electronic device engineering. It would be especially useful, Park said, for analyzing nanostructures when they are difficult to distinguish from one another.

"There is this tremendous excitement about nanostructures and nanoscale devices," Park said. "But there are a number of things we still need to figure out. One is, we have to be able to measure a large number of them simultaneously so we can have better control when we synthesize them. And that's easier said than done."

The results are reported in Nature Nanotechnology (already online and forthcoming in print Vol. DOI: 10.1038/NNano.2008.363). Collaborators include first author Adam W. Tsen, a graduate student of applied physics; Luke A.K. Donev, a graduate student of physics; Huseyin Kurt, a former postdoctoral associate at Harvard University; and Lihong H. Herman, a graduate student of applied physics.

For their technique, the researchers attached a pair of electrodes to the ends of an array of carbon nanotubes. They then used a laser to heat one nanotube at a time, which reduced the amount of electrical current flowing through it. The conductance change was proportional to the conductance of the nanotube being hit by the laser.

In essence, the nanotubes became temperature sensors, Park explained, and their conductance changes helped the researchers characterize which nanotubes were more or less conductive.

The research is supported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research and the National Science Foundation.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe