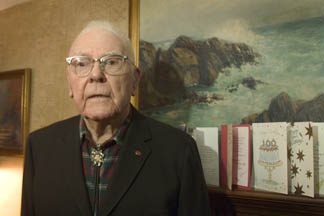

Cornell birth control pill pioneer Sam Leonard turns 100

By Krishna Ramanujan

When Samuel Leonard turned 100 on Nov. 26, few realized that he was a pioneer of one of the most significant medical advances of the 20th century.

Leonard played a key role in developing the birth control pill -- which liberated women's attitudes toward sex, galvanized the women's movement and launched the swinging '60s.

The Cornell University professor emeritus of zoology, a trailblazer of reproductive endocrinology, is credited with the idea of using estrogen as a contraceptive. He prevented pregnancy in rats with the female sex hormone in a 1931 study, three decades before human birth control pills hit the market.

"He is one of the great pioneers in the field of endocrinology," said colleague Ari Van Tienhoven, 83, professor emeritus of animal physiology at Cornell.

Another of Leonard's breakthroughs was to enable a female canary to sing, a talent possessed only by male canaries until Leonard gave the females testosterone, thus proving that the male sex hormone is needed to make beautiful music.

Perhaps his most seminal work was to show that the anterior pituitary gland secretes two gonadotropic hormones, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), that stimulate the testes and ovaries. While on a National Research Council Fellowship at Columbia University Medical School in 1931, a time when hormones were just being discovered and debate was raging over whether there were one or two gonadotropic hormones, Leonard wrote a paper demonstrating that two such hormones existed.

Aside from a stellar research career, Leonard also gained a reputation as a surgeon.

"Sam Leonard can smoke a cigar, talk and perform a hypophysectomy [remove the pituitary gland] on a rat at the same time," said Van Tienhoven. "He's an excellent surgeon."

Born in Elizabeth, N.J., in 1905, Leonard earned his Ph.D. in zoology from the University of Wisconsin, Madison, in 1931; served as assistant professor of biology at Union College from 1933 to 1937; and spent the next four years as an assistant professor of zoology at his B.A. alma mater, Rutgers University, before coming to Cornell as an associate professor of zoology in 1941. "[Edmund] Ezra Day interviewed me for the job," he said, referring to Cornell's fifth president (1937 to 1949).

Aside from being a dedicated scientist, Leonard's colleagues and family note his outstanding work as a teacher.

"Sam takes great pride in all the graduate students he has helped," said his daughter, Patricia Hoard, 62. "Students felt comfortable talking to him."

"I know for sure that half of my graduate students are dead," Leonard said. "I've outlived them." A week after he had hit the century mark, balloons still hung from railings leading to his modest Ithaca home, and helium still lifted more balloons inside. While Leonard's friends and family affectionately refer to him as grumpy, and his daughter said he has an "I-want-it-done-yesterday" attitude, his party was attended by 34 of his closest friends, while many others phoned to wish him well.

"It sounded good," Leonard said of the birthday party he could not see -- he has been blind for the last five years, the result of macular degeneration.

Before his blindness, he drove, cooked and took care of himself. Now, a caretaker is at his home from 7 a.m. to 1 p.m., seven days a week. He has outlived his wife as well as a son.

"It has been a good life," he said. "I married the most wonderful woman for 56 years and didn't go to bed mad once."

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe