In a seller's market, Cornell needs to recruit hundreds of new faculty, putting years-long pressure on budget

By Bill Steele

Over the next five years, Cornell needs to hire about 400 new faculty members -- a turnover of roughly one-quarter of the faculty. Is this a challenge or an opportunity?

"Having a large number of retirements is a huge benefit," says Robert Richardson, professor of physics and senior vice provost for research. "We can pick the faculty we want."

"In some disciplines, we will have to pay more to recruit in the current market," says Carolyn Ainslie, vice president for planning and budget.

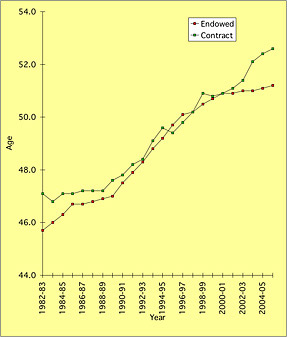

Blame it on the baby boomers. Born in the late '40s and early '50s, they swarmed into colleges in the '70s; schools expanded, hiring more faculty, largely from the older end of the boomer cohort. Although Cornell eliminated mandatory retirement at age 70 over a decade ago, the average age at retirement remains between 65 and 70, and the boomers are getting there. "From the number of faculty reaching that age we can project retirement," Ainslie says.

Up to now, the university has typically hired about 65 new professors each year to replace those who have retired, been hired away by other institutions or have left academic life. With the boomers retiring, Ainslie says, new hires will need to jump to about 80 per year to maintain the status quo. Meanwhile, some university initiatives call for expansion.

"This is going to put some pressure on the budget for the next five to 10 years," says Robert Harris, vice provost for diversity and faculty development. "We're constantly reviewing this matter and trying to think about creative ways for replacing our faculty in the future."

Among the creative approaches is what Harris calls "mortgaging lines." If Professor Jones, the world expert on widget engineering, will be retiring in two or three years, the department doesn't wait, but hires young Professor Smith, an upcoming player in the widget field, right now. "When we identify an outstanding scholar it's an opportunity to lock that person in for Cornell," Harris explains.

But the university will still pay two salaries during the overlap period. Add to that the cost of setting up a new laboratory, office space, support staff and other start-up needs, ranging from $100,000 plus in the humanities to more than $1 million in engineering.

Some of this may be recouped by the funding a new researcher brings in. In some cases the senior faculty member may go into "phased retirement," setting a date for retirement up to five years in the future and taking a reduced workload until then, perhaps at a reduced salary. A department also can balance start-up costs for newly hired faculty members against the saving in support costs for a person on sabbatical or other leave, or by not filling a line for a year. "We'll have pressure in the next decade in many significant ways," Ainslie says.

Starting salaries are climbing because universities are now in a seller's market, competing with other institutions facing the same baby-boomer crunch while there is anecdotal evidence that the number of Ph.D.s turned out in America is declining. And efforts to build strength in some key areas will include hiring many established, tenured professors. "The competition is already ferocious, but this hiring bulge presents additional challenges in hiring top-rate faculty," says John Siliciano, vice provost for initiatives.

One result is that the university is working harder to improve the quality of life for faculty, building on a recent survey of faculty work life by the provost's office. Coordination between the provost and the Office of Human Resources aims to help with affordable housing, child care, elder care and especially "dual career" issues.

If a new professor's partner is also an academic, finding a place for that person falls first to Vice Provost Harris. Essentially, Harris says, the partner is applying cold turkey for an opening in another department, provided such an opening exists. It's especially hard if both people are in the same field, he adds. A partner's job possibilities are not limited to Cornell, however. The Dual Career Program within the Recruitment and Employment Center of the Office of Human Resources has established relationships with other nearby institutions, including Ithaca College, Tompkins Cortland Community College, Cortland State University and Syracuse University.

For nonacademic jobs outside the university, Cornell is sometimes at a disadvantage because Ithaca is not a large urban area. But "We have really good relationships with other local employers, and there are many smaller companies and organizations looking for talented people," says Mary Opperman, vice president for human resources.

No matter how creatively the university approaches its hiring needs, the cost of hiring and maintaining a world-class faculty is bound to increase, and one major thrust of the current capital campaign will be to support those costs. But provided the financial issues can be managed, most academics see the large number of openings as a plus.

"This bulge creates the opportunity to accelerate shifts in our faculty composition," Siliciano explains. "More often than not the field is moving in new directions, [and] this wave of retirements and new hiring allows us to move more rapidly. If you invest heavily in young faculty in new fields, it pays off down the road."

Discussions of where the new directions might lie are widespread within and across departments. The New Life Sciences Initiative calls for growth in biomedical engineering and cell and molecular biology. In the social sciences, "We're drafting documents and having lots of conversations over the next six months," says David Harris, vice provost for social sciences. And the Faculty of Computing and Information Science, which launched a program of new hires in 1999, expects to add three more positions in the near future and perhaps more over the next 10 years.

Some departments may use "cluster hiring" to create a critical mass of researchers working in one field, in order to make the department attractive to students and future faculty. Or, hiring could be based on an institutional priority rather than the need to fill a specific post.

"An expert in plant molecular biology might end up in molecular biology and genetics, plant biology or plant breeding," suggests Steve Kresovich, vice provost for life sciences. "Or, we might delineate a constellation of talents and experiences we need and try to recruit several people together, across departments." In the life sciences, Kresovich adds, these arrangements between departments are coordinated through an advisory committee working under his office. Physical and social scientists are devising similar procedures.

The turnover also offers an opportunity to increase diversity. "The university looks at every available faculty opening with a mind to creating a very diverse candidate pool," says Opperman. But because women and underrepresented minorities are still a smaller subset of the overall population of academics, they don't always show up automatically as applicants, so the university has to work to identify the most diversified, talented pool, she says. "If you just post the job and you don't go out and recruit, you may miss the best qualified, most diverse possible candidates who just aren't looking at the moment. You have to recruit."

Overall, Robert Harris says, "We look at people who are going to add strength to our disciplines." And, he adds, Cornell has a lot to offer them. "Good people want to be around other good people."

We invite your comments on this story and will post your thoughts here. Only signed e-mail will be considered.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe