New program with Wildlife Conservation Society to enable Cornell veterinary residents to hone skills at Bronx Zoo

Performing root canal surgery on a tiger, treating a shell wound on a sea turtle, vaccinating a rare bird species to protect it from West Nile virus or diagnosing pathogens in a variety of species and settings. These are just some of the skills Cornell veterinary residents will learn in a new training initiative launched by the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and Cornell's College of Veterinary Medicine.

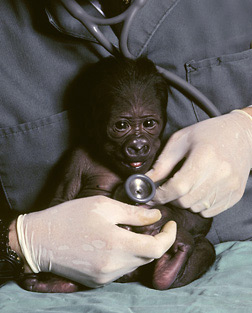

The initiative combines the academic rigor of a Cornell education with critical hands-on experience with a diversity of wild animals at the Bronx Zoo and other WCS facilities.

Cornell veterinary students in the initiative's two recently created residencies -- wildlife medicine and wildlife pathology -- will divide their three-year terms between Cornell's Ithaca campus and WCS facilities in New York City, while gaining a comprehensive understanding of animal-health issues.

The joint residencies are two of several collaborative programs in the new WCS-Cornell partnership, which also includes increasing animal-disease surveillance around the world, boosting veterinary expertise in other nations and developing a collaborative Global Center for Wildlife and Domestic Animal Health, to be located at the Bronx Zoo. WCS and Cornell, with the assistance of the U.S. Agency for International Development and the government of Zambia, also have launched a project to develop models for balancing socio-economic development with biodiversity conservation in southern Africa.

"This collaboration provides a unique combination of scientific rigor and higher quality of professional practice," said Donald F. Smith, the Austin O. Hooey Dean of Veterinary Medicine at Cornell.

Robert Cook, chief veterinarian and vice president of WCS Wildlife Health Sciences, added, "The WCS One World, One Health model will give the world's health organizations and agencies multidisciplinary practitioners who can really make a difference not only to wildlife but to the future health of domestic animals and people."

Residents in the wildlife medicine program will first study internal medicine, surgery, dermatology, epidemiology and other relevant topics at Cornell's College of Veterinary Medicine. They will then continue their training at WCS's Wildlife Health Center, the primary care facility for some 20,000 animals in the Bronx Zoo, the New York Aquarium and the Central Park, Prospect Park and Queens zoos.

Residents also could have opportunities to work with field veterinarians and biologists, applying what they have learned in the society's zoos and aquariums to wildlife health issues around the world.

Residents in the wildlife pathology residency will study comparative anatomy and the diseases of domestic and wild animals at Cornell first and develop their ability to diagnose pathogens in a variety of species. Residents will then hone their skills in disease identification at the Bronx Zoo and other WCS facilities, helping document poorly understood diseases and devising strategies to mitigate the threats of such emerging infectious diseases as West Nile virus or avian influenza.

"The partnership between WCS and Cornell offers both organizations a means of maximizing our complementary expertise and giving veterinarians the most comprehensive training to date," said Cook. "As we increase our understanding of how health issues move across animal and human divides, we realize that collaborative programs such as these are critical in ensuring the health of wildlife, domestic animals and humankind."

Media Contact

Sabina Lee

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe