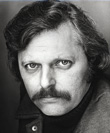

Retiring Stephen Cole leaves legacy onstage -- and off

By Daniel Aloi

Stephen Cole, professor of theater for almost 40 years at Cornell, will retire this year, leaving a legacy on campus and in the Ithaca theater scene.

He came to Cornell in 1968 from the University of Nebraska to help launch one of the country's first master's programs for actors. The theater department "was funded to expand, and [then-chair] James Clancy wanted to put in an M.F.A. program. In those days, that was the hot thing to do," Cole recalls.

In addition to training generations of actors, Cole was among the founders in the early 1970s of the Ithaca Repertory Company, which later became the Hangar Theatre, and he has acted in and directed numerous productions for Ithaca Rep, Kitchen Theatre Company and the now defunct Firehouse Theatre.

At 74, Cole is spry and literally young at heart -- he received a heart transplant on Labor Day 1994, from a donor 22 years his junior.

"I've had the best health of my life since; I get sick for maybe one or two days," he says.

The transplant followed years of illness and deteriorating health, including a failed 1987 bypass operation and a nine-year disability leave from Cornell -- during which time he still worked in theater in Ohio.

Born in New York City and raised in the Midwest, Cole started doing stand-up comedy at age 14 -- "I was hopelessly shy then" -- and danced in his first professional production at age 18. He has had his Actor's Equity card for 55 years, and even through illness and military service, he has stayed active in the theater.

During his last six seasons at the Schwartz Center, Cole specialized in comedy, directing Christopher Durang's "Betty's Summer Vacation" (2002-03), Thomas Gibbons' "Bee-luther-hatchee" (2003-04), Alan Ball's "Five Women Wearing the Same Dress" (2004-05), Alan Ayckbourn's "Comic Potential" (2005-06), Steve Martin's "Picasso at the Lapin Agile" (2006-07) and his final production, staged in October 2007, Ayckbourn's "Bedroom Farce."

In doing so his relationship with onstage comedy came "full circle," he says. "I started doing it at 19, with really masterful people [including mentor Barnard Hughes] -- and this became my fate. It's hard as hell."

Distinguished Cornell alumni who studied and acted with Cole include film and television stars Jimmy Smits, M.F.A. '82 ("L.A. Law," "The West Wing"), who starred in a 1981 Cornell production of "The Taming of the Shrew" set in Mexico; the late Christopher Reeve '74 ("The Remains of the Day," "Superman"), William Sadler, M.F.A. '75 ("The Hot Spot," "Trespass"), and Catherine Hicks, M.F.A. '74 ("7th Heaven," "Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home").

A second chance and 'a sense of wonder'

Following his heart transplant in 1994, Stephen Cole developed an interest in the inner self that will continue into his retirement.

"I was very lucky because I was practically dead; I was out of body twice," he says. "I was utterly and totally helpless when I woke up [after the transplant]; I had atrophied while I was sliding down to death."

He recovered over the next 10 months until he could walk normally, and he returned to teaching in 1996.

"It was a lot of time to lie there and think," he says. "The curious thing was I could remember all of my biography and my internal situations, but they seemed to be of somebody else. I felt like a little child. I came back with a kind of wonder. I remember stepping into the elevator in the Schwartz Center and I felt a sense of wonder that I was here. So I decided to go into consultation to find out about myself. Things started coming to fruition; it was a real blessing."

The psychological awakening that followed led to a continuing interest in helping people.

He is active with Compos Mentis, a group of psychologists and volunteer workers who operate a healing and learning center for mentally challenged people on a farm near the Cayuga Nature Center. The group offers poetry, art, meditation and other activities, "to just give them an outside experience of being normal," he says. Cole also is a teacher in the IM School of Healing Arts, a four-year program in personal development.

"After my heart transplant, everything changed for me, and psychologically, I wanted more of myself," he says.

Over the years Cole has seen the Cornell program grow and move into a new facility, from the department's old digs in Lincoln Hall and productions in Willard Straight Theatre.

"The great thing about the Straight was it was so restrictive, a small stage," he says. "The big stage at the Schwartz Center is not much of a challenge. I like the limits of the Flex Theatre and the Black Box; it makes me think harder."

Cole has enjoyed working with young people and encouraging them as actors to put their egos aside.

"That's been a principle of my teaching -- to empower individuals with their own power, not some version of mine," he says. "I had to pay attention to them and awaken their own dynamic. Because that's what happened to me."

Returning to Cornell in 1996 after nearly a decade away, Cole found a student culture that was as transformed as he was.

"The students have changed radically," he says. "In the '70s, the trick was to peel them off each other during acting exercises; when I came back in the '90s, it was hard to get them to hold hands. But actors are always actors; you need to get them to let go."

Like all veteran theater people, Cole has some good stories about onstage and backstage disasters. In his time, he has seen sets collapse midshow, audiences run for the exits and actors go way over the top at auditions.

During military service in Panama, he ran a small theater, and says, "I destroyed a promising enlisted man's career to do that."

He once was injured in between scenes during a play in Memphis, Tenn., while walking an actress' standard poodle that was left backstage.

"That dog took off; I twisted my ankle so bad and realized I was in trouble," he says. Knowing he had to deliver lines and props to get the play to its end, "I walked on in the middle of another scene, said what I had to say, walked off and fainted."

He has witnessed some memorably bad auditions, including one for M.F.A. students at the Kennedy Center where an actor swapped prosthetic arms while reciting Shakespeare.

"One of the great things about a life in the theater is all of the amazing stuff that happens that you don't get anywhere else," Cole says.

The audience exodus happened during another school's production of Chekhov's "The Seagull" during the American College Theatre Festival, hosted by Cornell in the 1970s.

"The theater was filled with people; there were judges in the second or third row in the Straight. Ten minutes in, I said, 'this is the worst production of Chekhov I've ever seen' and I went out into the lobby. Within five minutes or so, the whole audience came rushing out. The only ones left were the row of judges.

"The audience will always tell you something," he says.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe