Alum: Grand Central Terminal transformed America

By Claire Lambrecht

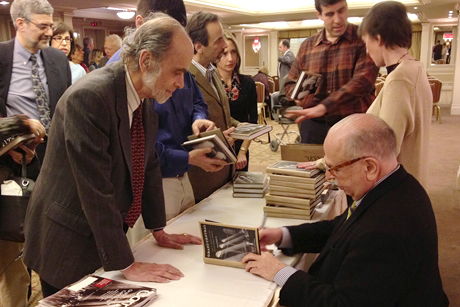

Beloved today, Grand Central Terminal came very close to being demolished in the 1970s, said Sam Roberts ’68, New York Times urban affairs correspondent and author of “Grand Central: How a Train Station Transformed America,” during a talk at the Cornell Club in Manhattan April 9.

“A judge ruled against Grand Central, against the city, saying that it didn’t have the power to declare it a landmark,” Roberts told 60 Cornellians in attendance. New York City, reeling from the fiscal crisis of the mid-1970s, couldn’t afford to appeal the decision.

That all changed when the Municipal Art Society received a call from Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. She, along with New Yorkercritic Brendan Gill and groups like the Municipal Art Society, appealed the case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, where they won.

This legal victory, Roberts said, reflected Grand Central’s success at integration with the city. “It wove its way into the fabric of New York City so that it couldn’t be ripped out. The real brilliance of the place, all of its architectural glories, was the way that it confirms the virtues of the urban ensemble. More than any other place I can think of, it embodies the voice of the city and the rhythms of urban America,” he said.

The origin of Grand Central was similarly dramatic. The two firms commissioned to design the structure were famously antagonistic.

“They created this sort of shotgun marriage of two architectural firms who never got along, who hated each other, were always at creative clash, but probably produced an architectural monument that was better than its individual parts,” he said.

Architectural flourishes like ramps, the glass walkway, and the 25,000-square-foot celestial ceiling, were products of this unhappy union.

Far from just a Beaux Arts building, Grand Central is also about people, Roberts said. “Grand Central turns out to have been the site of ransom demands, mail train robberies, triumphant homecomings, hope-filled sendoffs, the target of Nazi saboteurs and terrorist bombs,” Roberts said. The CBS studio where Edward R. Murrow delivered his “See It Now” broadcasts, for example, was located at Grand Central.

Today, in it’s centennial year, the terminal is a very different. After years of neglect, the building went through a major renovation in the 1990s. The panoramic Kodak Colorama sign has been removed. An Apple store now resides in the south balcony. Even with these changes, Roberts said, the building lives up to its original vision.

The ability to bring so many parties together is unique, Roberts said. “Grand Central is the product of local politics, bold architecture, a brutal flexing of corporate muscle, visionary engineering. No other building, to my knowledge, epitomizes the partnership that melded the best instincts of government with public-spirited private investment,” he said.

Claire Lambrecht ’06 is a freelance writer based in New York City.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe