Returning cicadas become smorgasbord for predators

By Blaine Friedlander

After a 16-year slumber underground, the 17-year cicadas – with their raucous rib-rendered buzz – will return in late spring to the Hudson Valley area and parts of Connecticut and Massachusetts, says Cole Gilbert, associate professor of entomology. He spoke at a Cornell-hosted journalist luncheon in midtown Manhattan April 24.

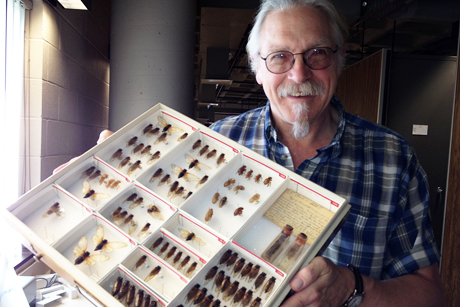

Don’t fear them, he says. They may be ugly critters, but cicadas don’t bite. “The adults have black bodies with bright red-orange eyes and legs. The major veins of the wings are a paler yellow-orange color,” says Gilbert. “It’s a garish beast.”

In its ecosystem role, the cicada invasion is like a Las Vegas smorgasbord for animal and bird predators. “Everybody eats 17-year cicadas. One evolutionary advantage of being underground for 16 years is that no above-ground predator can specialize in eating the periodical cicadas,” says Gilbert.

For cicadas, the best defense simply may be predator satiation. “There are so many cicadas, that predators get full, and they can’t eat another bite. This allows most individuals to survive,” he says.

With the large cicada populations comes a persistent buzz: Unlike crickets and grasshoppers, cicadas don’t use wings to make sound. Rather, Gilberts says they have a series of ribs on their abdomen that buckle and produce a series of popping sounds when a big muscle pulls on them. As the muscle pulls, the ribs pop in turn. When the muscle relaxes, the ribs pop back out and produce a quieter sound.

Across the eastern United States, separate populations – called broods – of 17-year or 13-year cicadas usually emerge in any given summer. In 2013, brood II of the 17-year variety is the only brood emerging, and the adults will populate a narrow band from western Massachusetts and Connecticut, as well as the Hudson Valley, south to northern and western North Carolina.

Biologically, these insects feed by sucking plant juices with straw-like mouthparts. The nymphs live underground for 16.5 years feeding on sap in roots and shed their skin periodically four times as they grow, according to Gilbert.

Nymphs dig a hole from the roots to the surface, but wait until the ground temperature is about 65 degrees Fahrenheit before emerging. Then they climb a nearby tree, wriggle from their nymphal skin, hang motionless and pump their wings. The cicada body hardens, and the adult can fly away. This process takes several hours, making the insect vulnerable to small predators, such as ants.

Adult cicadas live four to six weeks, but some broods in some locations have become locally extinct. That is, the population size got so small, the cicadas weren’t able to satiate predators and were subsequently wiped out.

Says Gilbert: “There are a few years out of every 17 when no periodical cicadas emerge anywhere in the U.S. We don’t know all the factors that contribute to the shrinking of population size to below the threshold for predator satiation. Habitat loss to human urbanization is certainly a possibility, as this has been a culprit in the decline of many other species. But, the situation with 17-year cicadas, however, may be more complex.”

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe