Fees cancel tax advantage of college savings plans

By Bill Steele

Government efforts to make it easier to save for college have unintended consequences, according to a Cornell economist. When you get a tax deduction for contributing to a college savings plan, your savings may be more than consumed by higher fees charged by plan administrators, according to research by Vicki Bogan, associate professor in the Charles H. Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management. Parents may be better off putting their money in ordinary, non-tax-exempt investments, she suggested.

“The government policies designed to make college more affordable could be creating market frictions which enable investment firms to charge excess fees,” Bogan said, adding that federal regulation may be needed “to preclude financial management companies from appropriating the benefits intended for individuals.”

Bogan’s analysis will appear in a forthcoming issue of the journal Contemporary Economic Policy.

In the early 2000s, Section 529 of the Internal Revenue Code was amended to create investment plans that would encourage parents to save for their children’s education. As a result almost every state offers “529 plans” that allow parents to deduct contributions from their state income tax. Like 401(k) retirement plans, 529 plans usually invest in a group of mutual funds.

Analyzing data from 2002 to 2006, Bogan found that the greater the tax advantage a state offered, the higher the fees charged by investment managers, even after controlling for such factors as the amount of competition in a state and the administrative structure of the plan. The statistics support an assertion that investment management companies set their fees based on the amount of tax saving offered by the state, she said. And if the state is receiving a share of the fees charged by plan administrators, Bogan added, it has an incentive not to regulate those fees, creating a “moral hazard risk.”

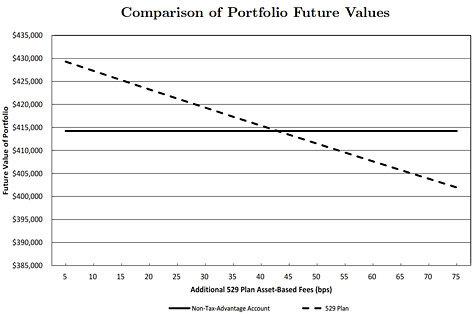

Bogan offers the example of parents investing $10,000 a year in a typical plan, starting when a child is born. Tax savings will amount to around $500 a year, depending on the investor’s federal tax bracket, and the parents would invest that money back in the plan. But fees – based on the growing value of the fund – will quickly reach $585 a year. “By year four or five…the annual asset-based fees completely cannibalize the state taxable income benefit,” Bogan reported. At the end of 18 years, the 529 fund could be worth thousands less than an ordinary mutual fund, depending on the fees charged.

“Households would be well advised to educate themselves about each specific educational savings plan prior to investing,” Bogan concluded.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe