Nabokov had 'perfect accord' with his father: new book

By Linda B. Glaser

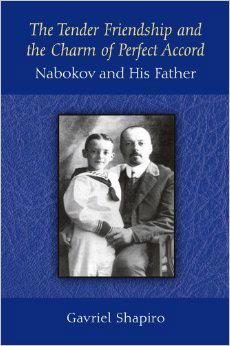

Bitter grudges, misunderstandings and general dysfunction fill the literature about great authors and their parents, so the uniquely positive relationship between Vladimir Nabokov and his father fascinated comparative and Russian literature professor Gavriel Shapiro. His new book, “The Tender Friendship and the Charm of Perfect Accord: Nabokov and His Father” (University of Michigan Press), is the result.

Shapiro’s book is an intellectual exploration of the connections between the father and the son rather than psychological deconstruction. He looks at the influence of the father’s worldview on the son by comparing the senior Vladimir Nabokov’s extensive writings to those of his son on such topics as jurisprudence, politics, the fine arts and sports.

“Nabokov senior was a Renaissance man: a great connoisseur of music, literature, theater and the fine arts, and a passionate lover of chess. He was also a keen lepidopterist and an avid athlete – all characteristics shared by his son,” Shapiro says. “The impact of the father on the son fascinated me.”

Upcoming book talk

Shapiro will talk about his new book April 10 at 4:45 p.m. in a public Chats in the Stacks program in 106G Olin Library. Books will be available for purchase and signing.

The senior Nabokov was a lawyer by training, a criminologist and a man with surprisingly modern views. In 1902, he wrote about child abuse in an article titled “Carnal Crimes,” which his son didn’t read until 1961, after he composed “Lolita.”According to Shapiro, there is no evidence that the two men ever discussed the subject, but it was clearly one of importance to both Nabokovs.

“‘Lolita’ is often misunderstood,” says Shapiro. “In fact, if you read it carefully you see that it was Nabokov’s courageous condemnation of child abuse at a time when the subject matter was completely swept under the rug. There were great similarities between the father, who identified child abuse as a crime, and the son, who shows the devastating effects of abuse on his characters.”

In the book’s conclusion, Shapiro writes that the Nabokovs lived up to the motto on the family coat of arms, “for valor.”

The senior Nabokov’s aristocratic lineage meant that he could have chosen to live a life of luxury, but instead he put himself at odds with the tsarist government, and that cost him his teaching position at the Imperial School of Jurisprudence. He co-founded the Constitutional Democratic Party in Russia; and when Lenin seized power and outlawed the party, Nabokov senior exposed the evils of Bolshevism from exile. His final act was to shield a former political ally from an assassin’s bullets.

Like his father, Nabokov spoke against Communism. In “Lolita,” and especially in “Pnin,” he was among the first to write about the atrocities of the Holocaust. In the early 1970s, Nabokov voiced his strong opposition to the political trials of dissidents in the Soviet Union.

The book’s appendices include several essays by the Nabokovs that have not been previously available in English, including an article by Nabokov senior on anti-Semitism and a lecture about opera by the purportedly music-disliking novelist.

Shapiro has written two other books on Nabokov – “Delicate Markers: Subtexts in Vladimir Nabokov’s ‘Invitation to a Beheading’” and “The Sublime Artist’s Studio: Nabokov and Painting.”

Linda B. Glaser is staff writer for the College of Arts and Sciences.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe