Study cracks brain's emotional code

By Karene Booker

Although feelings are personal and subjective, the human brain turns them into a standard code that objectively represents emotions across different senses, situations and even people, reports a new study by Cornell neuroscientist Adam Anderson.

“We discovered that fine-grained patterns of neural activity within the orbitofrontal cortex, an area of the brain associated with emotional processing, act as a neural code which captures an individual’s subjective feeling,” says Anderson, associate professor of human development in Cornell’s College of Human Ecology and senior author of the study, “Population coding of affect across stimuli, modalities and individuals,” published online June 22 in Nature Neuroscience.

Their findings provide insight into how the brain represents our innermost feelings – what Anderson calls the last frontier of neuroscience – and upend the long-held view that emotion is represented in the brain simply by activation in specialized regions for positive or negative feelings, he says.

“If you and I derive similar pleasure from sipping a fine wine or watching the sun set, our results suggest it is because we share similar fine-grained patterns of activity in the orbitofrontal cortex,” Anderson says.

“It appears that the human brain generates a special code for the entire valence spectrum of pleasant-to-unpleasant, good-to-bad feelings, which can be read like a ‘neural valence meter’ in which the leaning of a population of neurons in one direction equals positive feeling and the leaning in the other direction equals negative feeling,” Anderson explains.

For the study, the researchers presented 16 participants with a series of pictures and tastes during functional neuroimaging, then analyzed participants’ ratings of their subjective experiences along with their brain activation patterns. To crack the brain’s emotional code and understand how external events come to be represented in the brain as internal feelings, the researchers used a neuroimaging approach called representational similarity analysis to analyze spatial patterns of brain activity across populations of neurons rather than the traditional approach of assessing activation magnitude in specialized regions.

Anderson’s team found that valence was represented as sensory-specific patterns or codes in areas of the brain associated with vision and taste, as well as sensory-independent codes in the orbitofrontal cortices (OFC), suggesting, the authors say, that representation of our internal subjective experience is not confined to specialized emotional centers, but may be central to perception of sensory experience.

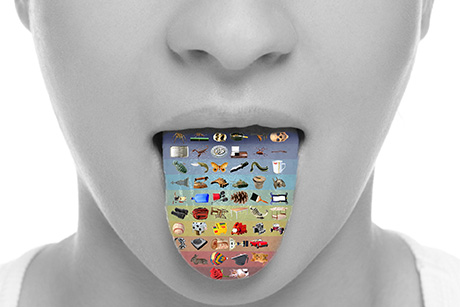

They also discovered that similar subjective feelings – whether evoked from the eye or tongue – resulted in a similar pattern of activity in the OFC, suggesting the brain contains an emotion code common across distinct experiences of pleasure (or displeasure), they say. Furthermore, these OFC activity patterns of positive and negative experiences were partly shared across people.

“Despite how personal our feelings feel, the evidence suggests our brains use a standard code to speak the same emotional language,” Anderson concludes.

The study was funded in part by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and was co-authored by Junichi Chikazoe, postdoctoral associate in human development at Cornell; Daniel H. Lee, University of Toronto; and Nikolaus Kriegeskorte, University of Cambridge.

Karene Booker is an extension support specialist in the Department of Human Development.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe