Asian studies professor tackles medieval mystery

By Linda Glaser

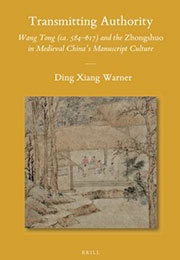

A controversy begun a thousand years ago in China may have met its match in Asian studies professor Ding Xiang Warner. Her recent book, “Transmitting Authority: Wang Tong and the Zhongshuo in Medieval China’s Manuscript Culture,” tackles the firestorm set off in the 11th century when a Chinese scholar challenged the very existence of revered Master Wenzhong, born Wang Tong (ca. 584-617).

The debate has raged on unchecked for centuries. Was Wang Tong indeed the teacher of the key advisers to the founders of the great Tang Dynasty (617-907), and therefore a source of the dynasty’s glory – or was he a virtual unknown? Was his text, the “Zhongshuo,” a Confucian-quality work recording the master’s sagacious utterances – or was it a forgery?

“I love mystery novels, and I thought this was a perfect mystery,” says Warner. Having written her first book on Wang Tong’s poet brother (“A Wild Deer Amid Soaring Phoenixes: The Opposition Poetics of Wang Ji”), she knew Wang Tong had existed historically as a teacher of Confucian classics, but how and why his legacy had become embroiled in controversy was a puzzle.

“The very features of the ‘Zhongshuo’ that attracted critics’ suspicions, accusations and outrage are those that reveal unexplored textual practices within medieval China’s literati culture,” she writes. Fascinated by the text’s social history, she realized that Wang Tong’s legacy was really a story of personalities and of the politics of social positioning within literati circles. Their effort to promote – or demote – Wang Tong’s cultural authority reflected their desire to transfer part of that authority to themselves. By increasing Wang Tong’s “cultural currency,” they augmented their own.

Warner traces the beginning of this process to Wang Tong’s immediate descendants, who, it seems, were committed to cultivating Wang Tong’s status as a latter-day Confucius, knowing that his increased prestige would bestow on his progeny a proportional renown.

This conferral of importance by Wang Tong’s stature as scholar or imposter continues with modern studies, says Warner. One aim of her book, therefore, is to remind modern scholars and critics of the danger of identifying too closely with the subject of their study. “In trying to right the wrong of history’s neglect of a figure, we consciously or unconsciously can be pulled by our own emotional impulse to frame the subject in the way we want the world to see it,” she says. “As scholars of textual and intellectual history, we need to keep a healthy distance and recognize that the culture we study is a product of these human shapings.”

Warner’s primary scholarly focus is as a literary historian of classical Chinese poetry. She recently published an essay, “An Offering to the Prince: Wang Bo’s Apology for Poetry” (in “Reading Medieval Chinese Poetry: Text, Context, and Culture”) that examined how literati envisioned the role and function of poetry, both in the way it shapes their own identity in court-centered culture and how that could help them gain entrance into the court system.

The economic, cultural and political vibrancy in medieval China was drastically different from Western experience, notes Warner. “I often compare it to the Renaissance period in Europe. Later centuries look back on it as the Golden Age that can never be recovered.”

This spring Warner is teaching a course on Tang poetry, read in the original, that examines poetry’s social function in the Tang court. She’s also teaching Tales of Crime and Justice from Traditional China, which uses translated texts to examine cultural ways of looking at criminality and justice, and the problem of vigilantism.

“Thinking about contemporary issues – such as at what point is taking justice into your own hands a moral imperative and at what point does it cross over into anarchy – inspired me to go back to ancient China and see how they grappled with these same issues,” says Warner.

Linda B. Glaser is a staff writer for the College of Arts and Sciences.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe