Saving history, one tape at a time

By Gwen Glazer

Remember VHS tapes? Betamax? Super 8? Open-reel audio?

Information stored on magnetic tape is in danger from physical degradation, playback obsolescence and other causes. A new campuswide partnership is trying to save them, along with audio-visual materials of many stripes that Cornell faculty members hold in their offices and use in their research and teaching.

Cornell University Library, Cornell Information Technologies (CIT) and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology are working together to locate, stabilize and digitize these materials. The Library of Congress estimates information stored on magnetic tape has only 10 or 15 years left before it is lost.

“Inaction has a high cost: the longer we wait, the more we lose,” said Danielle Mericle, director of the library’s Digital Media Group. “Some of these playback machines, there’s only one in the entire world or one person who can still fix them; the longer we wait, the more the material will deteriorate. Costs go up exponentially, and we might lose it altogether.”

Cornell could have as many as 500,000 unique endangered materials, said Tre Berney, multimedia specialist in the Digital Media Group, and their loss would be a “slow catastrophe.” University Athletics, the University Archives and all colleges and units likely hold these vulnerable materials.

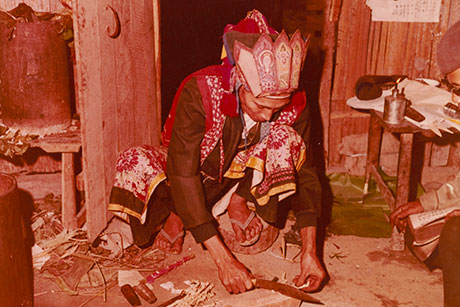

One example comes from the Southeast Asia Program, where Hjorleifur (“Leif”) Jonsson, Ph.D. ’96, works as a visiting fellow. Jonsson is an associate professor of anthropology at Arizona State University; during his graduate work at Cornell, he studied the anthropology of the Mien people, a minority group in southern China and Southeast Asia.

As a graduate student at Cornell in the 1970s, Richard Cushman also worked with the Mien people in Thailand, speaking with chiefs and gathering oral histories, chants, genealogies, curing spells, magical formulas, and discussions of the Vietnam War and current events. Cushman recorded those conversations on reel-to-reel audiotapes, which can only be played on a handful of machines that still exist.

Many of the tapes were housed among 18 boxes of Cushman’s archival materials in the library’s Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections. All together, Jonsson had located 92 recordings of rare conversations in an almost-dead language – and he couldn’t play them.

With an internal library grant aimed at preserving “at-risk” content, Jonsson – along with Greg Green, curator of the Echols Collection, and the Digital Consulting and Production Services team – began sorting the tapes, playing them on a reel-to-reel machine and digitizing some of them.

The Mien use three different dialects. Many people still speak the everyday language, but the ritual and song languages are rarely spoken; Jonsson said he thought Cushman might be the only Westerner who ever became proficient in it.

“We’re the last bastion for some of the equipment that you need to play these things on,” Berney said. And the threat isn’t over.

“Typically people aren’t using magnetic tape anymore; now, they’re digitally capturing to a card and inputting to a computer – but digital materials are also very fragile and complicated, and there’s no methodology in place for preserving them either,” he said. “We could be facing the same situation a decade down the road, so we need to start putting some systems in place right away to avoid another situation just like this.”

“It’s the right first step to get a handle on what we have right here at Cornell,” Mericle added. “High-value items might literally be sitting under people’s desks, and they just don’t know it.”

Gwen Glazer is the staff writer/editor at Cornell University Library.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe