Bailey Hortorium Herbarium stems from Cornell's roots

By Krishna Ramanujan

The fourth floor of Mann Library on campus houses the Liberty Hyde Bailey Hortorium Herbarium, a collection of more than a million dried and preserved plant specimens.

The roots of this botanical library of pressed leaves, branches, flowers and seeds go back to Cornell’s beginnings. In 1869, Andrew Dickson White purchased a collection called the Wiegand Herbarium for $1,000 from Horace Mann Jr., the son of an educator who helped develop the nation’s public school system and an acquaintance of naturalist Henry David Thoreau. Then, in 1935 Cornell plant biologist Liberty Hyde Bailey donated his private 150,000-specimen herbarium to Cornell.

The two herbaria were combined in 1977 under the umbrella of the Hortorium, a Cornell department in the Plant Biology Section.

Bailey coined the word hortorium to mean “a collection of things from the garden,” said Peter Fraissenet, assistant curator of the herbarium, one of the largest university-affiliated collections of preserved plant materials in North America.

“It’s a huge library of biodiversity” that is used as a primary source of information for studying taxonomy, evolution and conservation, said Kevin Nixon, the herbarium’s curator. Its catalog indicates when certain species arrived in the collection, providing evidence, for example, when invasive species – like garlic mustard – were introduced in a region. And researchers may acquire samples for modern genetic and chemistry studies. Specimens may even show signs of diseases, Nixon said.

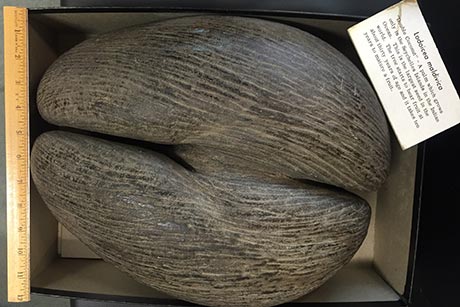

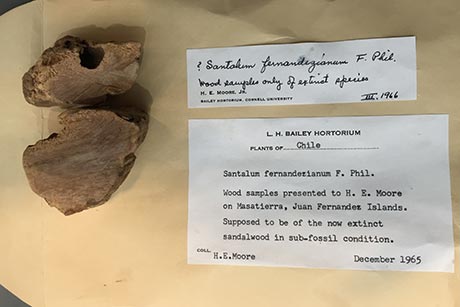

Specimens include such botanically or historically significant samples as the world’s largest seed, called a “double coconut,” a 1-foot-by-half-foot unhusked center from the fruit of a palm called a Coca de Mer from the Seychelles; semi-fossilized wood samples from a now extinct sandalwood from the Juan Fernandez Islands; and an Escallonia, a flowering evergreen shrub from Tierra del Fuego, off the southern tip of South America, collected during Captain Cook’s first voyage in 1769.

Among quirkier items are lotus leaves used in food preparation from a New York Chinese restaurant; leaves from a gourd from Bailey’s garden, including the seed packet; and a 1985 photo of a plate with a plant painted on it, from the Consulate-General of Japan, with a request to identify the plant.

The Hortorium collection is especially strong in species in the genus Quercus (oak), which is Nixon’s specialty, and the genus Rubus (brambles). It houses “arguably the best palm collection in the country,” in large part due to Bailey’s collection, Nixon said. Regional specialties include North America, the Northeast and New York, the Caribbean and eastern Mexico.

New specimens typically come from staff and students who donate samples from their studies, and from other herbaria that share their duplicates, though international laws have made plant prospecting and crossing borders with plant samples more difficult, Nixon said.

Once they arrive at the Hortorium, “new specimens are put in a [special walk-in] freezer for 24 hours,” to kill cigarette beetles and other insects that are known to infest such collections, before they are permanently mounted on herbarium sheets, said Anna Stalter, the collection’s associate curator.

Still, the long-term future of the herbarium is clouded by declining funds for natural collections of all kinds – and for the fieldwork that complements such libraries, Nixon said. Meanwhile, students and volunteers are digitizing the collection.

As it stands, “we may not be here in 20 years,” Nixon added, replaced by online-only, virtual memories of the collection – and its roots in early Cornell history.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe