Cornell Rewind: Keeping the faith in a nonsectarian way

By Elaine Engst and Blaine Friedlander

“Cornell Rewind” is a series of columns in the Cornell Chronicle to celebrate the university’s sesquicentennial through December 2015. This column will explore the little-known legends and lore, the mythos and memories that devise Cornell’s history.

The charter of Cornell University includes a remarkable statement: “And persons of every religious denomination, or of no religious denomination, shall be equally eligible to all offices and appointments.” These sentiments, radical for the 19th century, reflected the ideals and experiences of the founders, Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White. For both men, religion was a private matter, and religion would be a private decision for Cornell students, faculty and staff.

When Cornell’s charter was signed, clergymen served as the presidents of Harvard, Yale, Dartmouth and Penn.

Controversy dogged Cornell’s commitment to nonsectarianism from the start. When the university opened in 1868, the governor of New York had been scheduled to speak at the Inauguration Day ceremony. He withdrew – at the last moment – to elude criticism. White scribbled on his program: “But Gov. Fenton was afraid of Methodists & Baptists & other sectarian enemies of the University & levanted the night before leaving the duty to Lieut. Gov. Woodford who discharged the duties admirably.”

Walter Mayer Rosenblatt, a Jewish student, entered with the university’s first class in 1868, although he stayed only a year. In the early days, Jewish students were well integrated in the new nonsectarian university.

Upon White’s retirement, alumnus John Frankenheimer (Class of 1873) wrote to him: “At the time I entered college, the spirit of narrow-minded sectarianism prevailed in almost all of the colleges of the land, except Cornell. It was this among other influences that brought me to Ithaca. That during my life at Cornell I was never subjected to any of the annoyances and affronts which bigotry and race-prejudice call forth at other colleges, was due, I believe, to the liberalizing influence which you and your teachings exerted upon the students.”

The son of a New York City rabbi, Felix Adler arrived at Cornell to teach in 1874. New York philanthropist Joseph Seligman funded Adler specifically as a professor of Hebrew and Oriental literature and history. As his lectures were enthusiastically received, it was among the earliest appointments of a Jewish faculty member at any American university.

Despite Seligman’s support of Adler, Cornell’s Board of Trustees felt it unwise to have professors selected outside of university control. Adler left Cornell in 1876 and later founded the New York Society for Ethical Culture. He periodically returned to Cornell to lecture and later became founding chair of the National Child Labor Committee, and he served on the Civil Liberties Bureau, later known as the American Civil Liberties Union.

Sage, Mott and missionaries

After providing funds to build Sage College, which housed the university’s female students, university benefactor Henry W. Sage believed that Cornell needed a dedicated building for religious services. Designed by Charles Babcock, Cornell’s first professor of architecture, Sage Chapel opened in 1875.

Students founded a Cornell chapter of the Young Men’s Christian Association in 1869. By 1886, the Christian Association of Cornell University (renamed in 1872 to reflect the inclusion of women), under the direction of John R. Mott, Class of 1888, began calling for a dedicated building. Mott and fellow students raised nearly $10,000. In June 1887, trustee Alfred S. Barnes, a New York publisher, contributed $40,000. Designed by William Henry Miller, Barnes Hall – erected between Sage College and Sage Chapel – was dedicated in 1889.

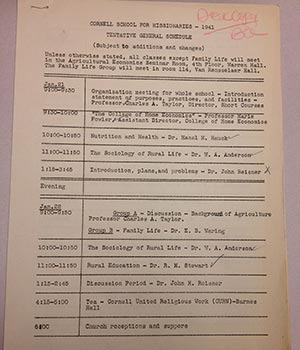

Years after his graduation, Mott, who would share the Nobel Peace Prize in 1946, served as general-secretary of the International Committee of the Y.M.C.A. (1915-1928) and president of the Y.M.C.A.’s World Committee (1926-1937.) While the Christian Association sponsored missionary activities earlier, a Cornell-in-China Club began educational efforts in China in 1922. These led to Cornell’s first big international project, a plant improvement program at the University of Nanking in China. Mott and John H. Reisner (M.S., 1914), a missionary who became dean of the College of Agriculture at Nanking, requested that Cornell offer a short agricultural course for missionaries.

The program – a four-week course on various components of agriculture, called the Cornell School for Missionaries – lasted about three decades. A 1960 Cornell Daily Sun article reminded readers: “However the university’s missionary programs make no attempt to influence the religious faiths of any participants. Except for voluntary participation in activities of Cornell United Religious Work or one of the Ithaca churches, the experience here is a purely secular one although, eventually, put to religious use.”

Cornell United Religious Work

Early groups on campus formed for Catholic and Jewish students, who worshipped in the Ithaca community. In 1929, however, in recognition of its expanded mission, the Cornell University Christian Association changed its name to Cornell United Religious Work (CURW). Father James Cronin became the first priest to join the Cornell Newman Club on a full-time basis in 1929, and Rabbi Isidor Hoffman, director of the Cornell Chapter of Hillel, also served as rabbi of Ithaca’s Temple Beth El.

CURW held discussion groups, lectures, suppers, a “marriage preparation series” and noncredit courses in religion. It also sponsored forums, lectures and discussions of public questions, and sponsored local and national service activities. In 1952, Anabel Taylor Hall opened as an “Interfaith Center.” Currently, CURW includes 30 affiliated communities, including Protestant, Catholic, Jewish, Muslim, Hindu and Buddhist.

Responding to grief

Three days after the Sept. 11 attacks, Cornell – in its nonsectarian way – faced the immense campus grief. About 12,000 Cornell students, faculty and staff, along with community members, gathered on the Arts Quad to share in a national day of prayer and remembrance. Arguably, it was Cornell’s largest gathering in a nonsports and nongraduation event.

Cornell President Hunter Rawlings emphasized Cornell’s values: “In the midst of this week’s tragic events, that we reaffirm Cornell’s core value of academic freedom and the responsibility that goes with it. What can we do to help the nation bind up its wounds? We will do what we do best: educate our students in open classrooms … That is the best response to the evil of terrorism…”

Rev. Kenneth I. Clarke Sr., director of CURW, reminded the gathering not to vent their anger toward blameless cultures, races and faiths. “We pray, instead, that we may be inspired by the countless examples of men, women, boys and girls across this land, indeed across this world, who have offered help, assistance, comfort, compassion, love and support.”

Sadness permeated the Cornell gathering. The Cornell Glee Club and Cornell Chorus, along with a local musician, Uganda-born Samite, sang “Ani Oyo,” a song of healing and hope. Rawlings concluded the service, “I look out and I see many friends, many colleagues from the Cornell community. I thank you all for everything you have done this week and [will] continue to do in the coming weeks,” he said. “Now turn and greet each other and offer your help, your support, your best wishes.”

The nonsectarian provisions in the charter – which Frankenheimer termed the “liberalizing influence” – contributed to a warm, collective kindness. When Hurricane Katrina flooded New Orleans, Cornell welcomed 200 Tulane University students and faculty for the fall 2005 semester, and the College of Veterinary Medicine sent emergency supplies to the Louisiana State University School of Veterinary Medicine in Baton Rouge, along with veterinary residents. For years, after the water receded, Cornell students returned to help rebuild the city.

Cornellians provided medical care and engineering help after the devastating earthquake struck Haiti in 2010. And close to home, after the April 14 Stewart Avenue fire displaced 44 students and two staff members, Cornell secured shelter and provided them with clothes, food and supplies.

In the 19th century, building Cornell on a foundation of nonsectarianism was a bold and radical deed that continues to reap blessings 150 years later.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe