Cornell Rewind: A secular School for Missionaries

By Elaine Engst and Blaine Friedlander

“Cornell Rewind” is a series of columns in the Cornell Chronicle to celebrate the university’s sesquicentennial through December 2015. This column will explore the little-known legends and lore, the mythos and memories that devise Cornell’s history.

From its founding Cornell has been a secular place, but when the university offered the Cornell School for Missionaries from 1930 to 1964 – an annual four-week course for veteran missionaries on furlough – it became instantly popular.

Missionaries from all over the world representing a variety of religions attended to learn how to teach citizens to bolster crops and improve their communities. The school was so popular that in 1941 the College of Agriculture added a one-year missionary course.

The School for Missionaries was an outgrowth of Cornell’s first big international project, a plant improvement program at China’s University of Nanking. John Mott, Class of 1888, who had served as general-secretary of the International Committee of the YMCA and as president of the YMCA’s World Committee, and John H. Reisner, M.S. 1914, a missionary who became dean of the College of Agriculture at Nanking, requested Cornell offer a short agricultural course for missionaries.

Patterned after the Cornell model, other land-grant institutions started offering schools for missionaries on furlough.

“The university’s missionary programs make no attempt to influence the religious faiths of any participants. Except for voluntary participation in activities of Cornell United Religious Work or one of the Ithaca churches, the experience here is a purely secular one although, eventually, put to religious use,” explained a story in a 1960 Cornell Daily Sun.

‘Comfortable rooms may be engaged’

Cornell’s School for Missionaries charged no tuition, but in the 1940s Cornell imposed an enrollment fee of 50 cents. The missionary students paid “board” – meals cost from $5 to $8 a week, and as a Cornell brochure put it, “comfortable rooms may be engaged … from $3 to $4 a week for each person” for double occupancy. Missionaries paid from $3.50 to $5 each week for a single room.

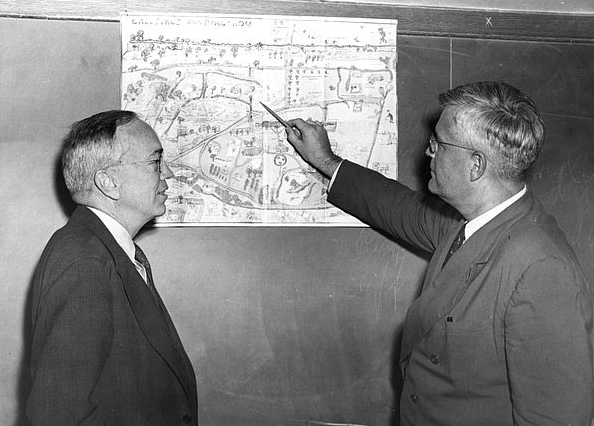

Many Cornell professors enjoyed imparting their useful knowledge. In the course’s 1940s heyday, Charles Arthur “Charlie” Taylor (Extension) organized the agricultural courses around soils, crops, livestock, controlling insects and vegetable gardening.

Rolland M. Stewart (Rural Education) helped the missionaries understand social structures of rural communities, plus the influence of tradition and custom, while Frank Morrison taught animal husbandry, Karl H. Fernow taught plant pathology and Howard W. Riley taught agricultural engineering.

Hazel M. Hauck’s daily class on nutrition and health taught good food selection, how foods contribute to health and how to understand diets in communities while exploring ways to improve them.

With time in short supply for the furloughed missionaries, afternoons and evenings were devoted to field trips, seminars and conferences. But, according to the Cornell Alumni News from Feb. 17, 1938, the visiting missionaries were “in demand as speakers at nearby rural churches and Grange halls. Recently talks are reported on experiences in China, the Belgian Congo, the Straits Settlements and Syria, to mention but a few.”

‘The eggs hatched!’

The missionaries provided brief autobiographies to their Cornell professors and wrote of their time serving in foreign lands.

Ruth Thomas and her husband, Howard Thomas, went to a leper colony in Yunnan province on the Burmese border with southwestern China as missionaries with the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions in 1937. Ruth Thomas oversaw medical services and training, while Howard coordinated the colony’s administration. Later Ruth Thomas wrote: “In December 1941, we were unfortunate enough to be in Bangkok, Thailand, and became [Japanese] prisoners of war. We were in the first exchange of prisoners of war from the Far East, returning on the M.S. Gripsholm in August 1942.”

The couple attended the 1943 missionary school, studied at the Graduate School, where they both received master’s and doctoral degrees from Cornell. Their dissertations were based on their work in China: Howard E. Thomas, “The Impact of the War upon a Rural Community”; and Ruth Margaret Hatcher Thomas, “An Educational Program for Leper.”

Then, both taught on the Cornell faculty, with Howard Thomas in rural sociology and Ruth Thomas in home economics.

H.A. Boyd began his missionary career in 1912 in China and by the 1940s organized reconstruction and economic planning projects there.

Mary Mansfield served as a missionary in Alberta, Canada, to a Ukrainian colony. She insisted on being addressed “Miss” in her letters, and wrote about the Ukrainian colony in that “our work there is almost entirely rural and chiefly with women and children.”

Mrs. Richard Baird was a “missionary wife” in Korea, who taught homemaking and health. “The most unusual feature of my work has been the unexpected demands upon me,” wrote Mrs. Baird in her Cornell School for Missionaries biography. “Once when my husband left some precious eggs of the Peking goose in my care, I had to take them to bed with me because the old hen left her nest too soon. The eggs hatched!”

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe