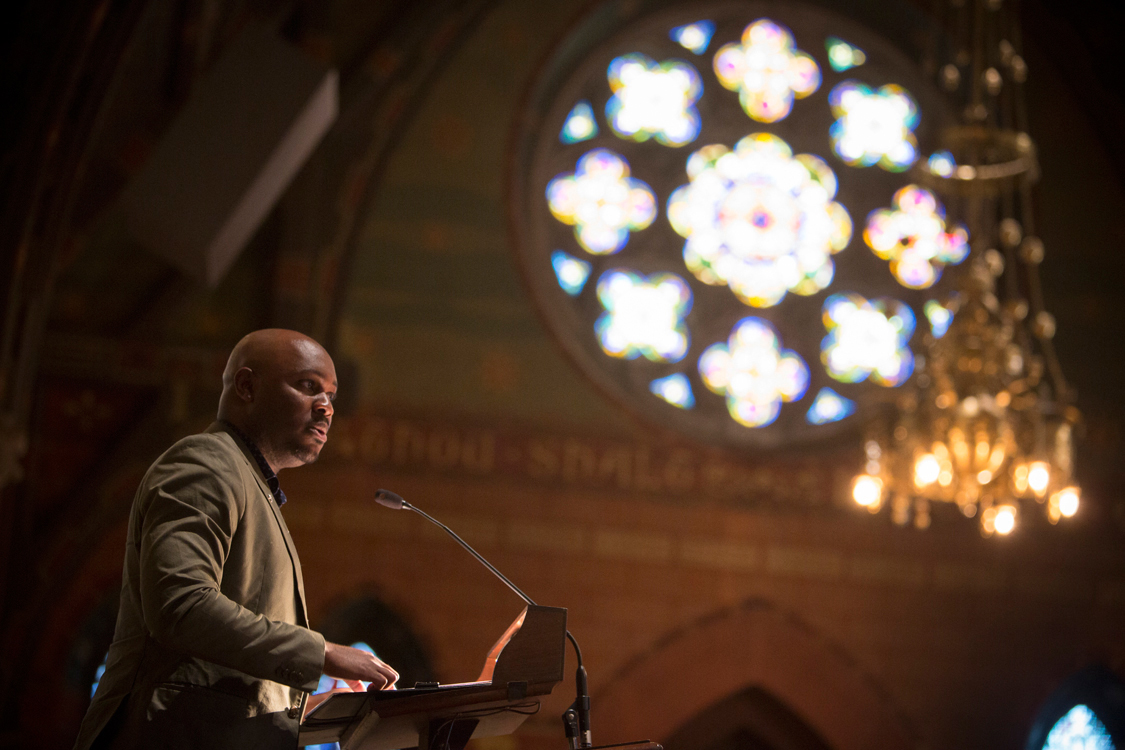

Sharing life's stories brings hope, Cornell Woodson says

By Nancy Doolittle

Growing up in Camden, New Jersey – a city with the worst educational system and the most murders per capita in the U.S. – as the son of parents who made less than $25,000 a year, Cornell Woodson was bullied in school, taunted and tormented because his classmates thought he was gay.

Currently associate director for diversity and inclusion in the ILR School’s student services office, Woodson shared those memories and how they shaped his thinking and his career at Soup and Hope Feb. 4 in Sage Chapel.

Woodson’s classmates happened to be right, but “back then, I didn't even understand what that meant. For the life of me, I could not fathom what my peers saw that made them target me,” Woodson said. “I have been jumped by groups of people more times than I can remember. I’ve had my locker slammed into the side of my head. My peers would chase me home while throwing rocks at me.”

Though the bullying stopped in middle school when he fought back, by then he had internalized the thoughts and opinions of his peers that he didn’t belong, was not good enough and did not deserve to exist, Woodson said.

“For as long as I can remember, I have suffered from what many scholars call imposter syndrome: the idea that I am a fraud and don’t deserve any of the success I have.”

He diminished his achievements to being lucky – simply being in the right place at the right time.

“Even to this day, I still find myself unworthy of what I have. I’m still asking: ‘how did I get here?’”

But having had those experiences and feelings helped Woodson relate to the high-school students he taught with Teach for America after graduating from Ithaca College in 2009. He had 180 students in Atlanta: “They did not come to class, they didn’t do homework, they talked on their phones while I taught, and they even slept,” he said.

When he talked with his mother on the phone, he told her he wanted to quit.

After allowing him to vent, she said, “Get over yourself.” She explained that though she had not been able to give him much, others had invested in giving him a chance for success. “It’s your turn to pay it forward,” she said. That feedback changed Woodson’s attitude.

“I started listening to their stories and found that they had experienced similar life experiences to my own and some even worse,” Woodson said. “While it does not mean I could completely understand their pain, I could relate. I could create a space where their stories were validated.”

The young men shared stories of wanting to be loved by their fathers; the young women shared stories of sexual assault and the feeling they had nothing to offer the world.

“These stories consumed their minds, and no wonder school was the last thing they were thinking about,” Woodson said. The students and Woodson bonded through their shared experiences; because Woodson helped the students see themselves differently, he became known as “Pops.”

“I was an example of how possible it is to overcome life’s struggles,” Woodson said. “Because I could relate in some way to their personal stories, we could support one another through the journey of understanding what it all means.”

Woodson realized that his childhood experiences and imposter feelings “all made sense now;” they help him identify with and help others. Woodson dedicated himself to social justice and to supporting students from marginalized backgrounds.

“I subscribe to the idea that what we are going through or have gone through isn’t always about us or for us. Sometimes it’s for the people that we have yet to meet,” Woodson said. “I truly believe we experience a life event and overcome it because, at some point, our path will cross with someone who is going through the same thing.”

Then we can move past our internalized thoughts and share our stories, “so that someone else might see hope in their own,” Woodson said.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe