Golden Goose Award honors bee expert's impact on computing

By Krishna Ramanujan

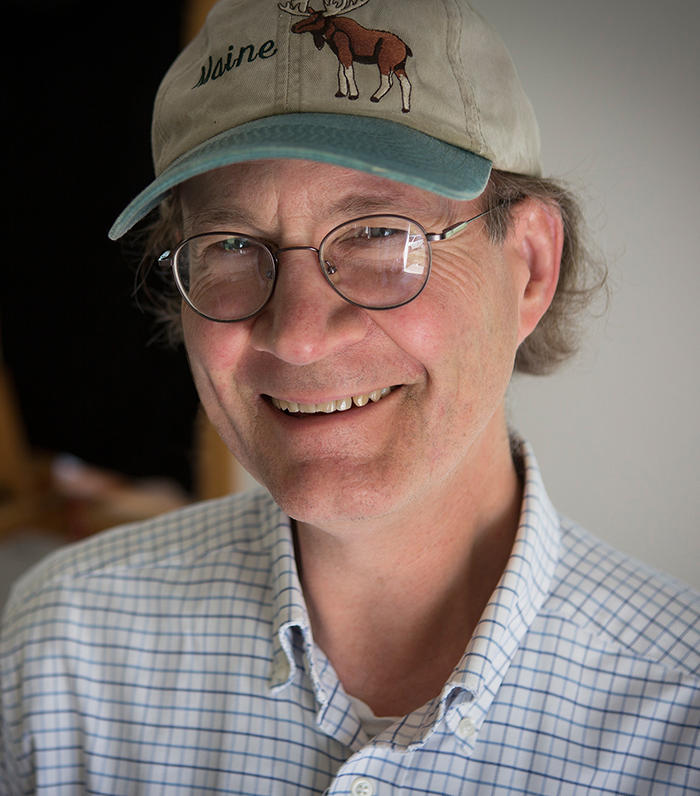

A system described by Cornell bee expert Thomas Seeley for how foraging bees in a honeybee colony distribute themselves among flower patches has been adapted and applied to the $50 billion web hosting industry.

Now, Seeley and four engineers from Georgia Institute of Technology will share the Fifth Annual Golden Goose Award for the “honeybee algorithm,” honoring their work to understand how honeybee colonies are organized to optimally forage for nectar, which unexpectedly led to the development of an algorithm used by major web hosting companies to streamline internet services.

“The Golden Goose Award highlights federally funded basic research that yields seemingly unrelated results and ideas that are game-changing for society,” said Cornell Interim President Hunter Rawlings. “The curiosity-driven culture of research universities is uniquely suited to promoting such work.”

“For the agencies that fund research, it’s a golden example of how funding something that seems esoteric – how a honeybee colony is organized – can produce economically valuable results,” said Seeley, the Horace White Professor in Biology in the Department of Neurobiology and Behavior in the College of Arts and Sciences.

Seeley will share the award with Craig Tovey, John Hagood Vande Vate and John J. Bartholdi III of Georgia Institute of Technology, and Sunil Nakrani, a senior data scientist at Kognitio and a former visiting scholar and postdoctoral fellow at Georgia Tech. Seeley and colleagues will receive their award at a ceremony Sept. 22 at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.

The research began in the 1980s when Seeley, funded by the National Science Foundation, investigated how a bee colony distributes its foragers among flower patches to maximize efficiency.

Seeley tagged each bee in a colony for individual identification then took the colony to the Adirondack Mountains, which are virtually devoid of wildflowers. He set up two “nectar” sources – one with low-concentration sugar water and another with a high concentration – in opposite directions 500 meters from the hive, a typical distance that bees travel to flowers.

His experiments revealed that when a bee visits a high-quality food source, she returns to the hive and reports her success with a vigorous “waggle” dance. The more profitable the nectar source, the longer the dance lasts. The dance also conveys the direction and distance to the food source.

In 1988, Seeley was interviewed about this work on National Public Radio, and Vande Vate heard it. He was intrigued and, with Bartholdi and Tovey, created a mathematical analysis to understand how effective the bees were at foraging for nectar using their self-organized system. But the math could not duplicate the bee’s actual efficiency. After they asked Seeley to collaborate, Tovey met with Seeley and they ran more experiments in the Adirondacks, which tested how well a colony distributes its foragers among nectar sources. They found that as a high-quality food patch gained bees and became less profitable for each bee, lesser sources were advertised and more bees were directed to them.

“The bees are allocated so that all are experiencing the same profitability,” Seeley said. By taking into account the highly variable conditions of the bee’s food sources, the researchers were eventually able to show mathematically how the bees could be such efficient foragers.

About the Golden Goose Awards

The Golden Goose Awards are given “to groups of researchers whose seemingly obscure, federally funded research had led to major breakthroughs in biomedical research, medical treatments, and computing and communications technologies,” according to the award’s website.

They were created in response to Sen. William Proxmire (D-Wisconsin), who from 1975 to 1988 issued monthly Golden Fleece Awards, which targeted federally funded research that appeared impractical and was deemed wasteful.

Rep. Jim Cooper of Tennessee, in an effort to counter Proxmire’s example, envisioned the Golden Goose Awards almost two decades ago. Cooper’s vision became a reality in 2012 when a coalition of nine business, university and scientific organizations – including the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Association of American Universities, and Association of Public and Land-grant Universities – created the Golden Goose Award.

Fifteen years later, Nakrani talked to Tovey about how companies hosting computer servers could meet the variable demands of internet traffic. It was then that Tovey made the connection between Seeley’s bees and issues with server networks, as both systems must efficiently distribute labor among job sites.

Nakrani and Tovey created the “honeybee algorithm” to help web hosting companies effectively allocate servers in the face of huge, unpredictable fluctuations in internet traffic and varying fees for services provided. To maximize profit, companies must keep their server computers busy at high-fee, high-demand websites as fees and demand fluctuate. Borrowing from the bee’s waggle dance in a hive, Nakrani and Tovey programmed an internal automated advertisement board that communicated with servers about traffic needs of different websites. When websites (flower patches) were in high demand and offered higher pay (nectar), those ads (waggle dances) were more frequent and lasted longer, thereby recruiting more servers (worker bees). Conversely, as demand and fees declined, so did the number and length of the ads. The system could be applied to optimizing high-network demand, energy use or price, for example.

In tests, a system based on the honeybee algorithm increased profits by 5 to 25 percent compared with a hypothetical best-possible stable allocation, because the bee-derived system adapted quickly to changes in internet traffic. “The bees turned out to be even smarter than we thought,” said Tovey.

“I’ve always enjoyed working on things that nobody else is working on,” Seeley said. “It’s rewarding to know you can follow your curiosity and it actually pays off.”

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe