Fuertes Observatory’s new museum goes 'back to the future'

By Blaine Friedlander

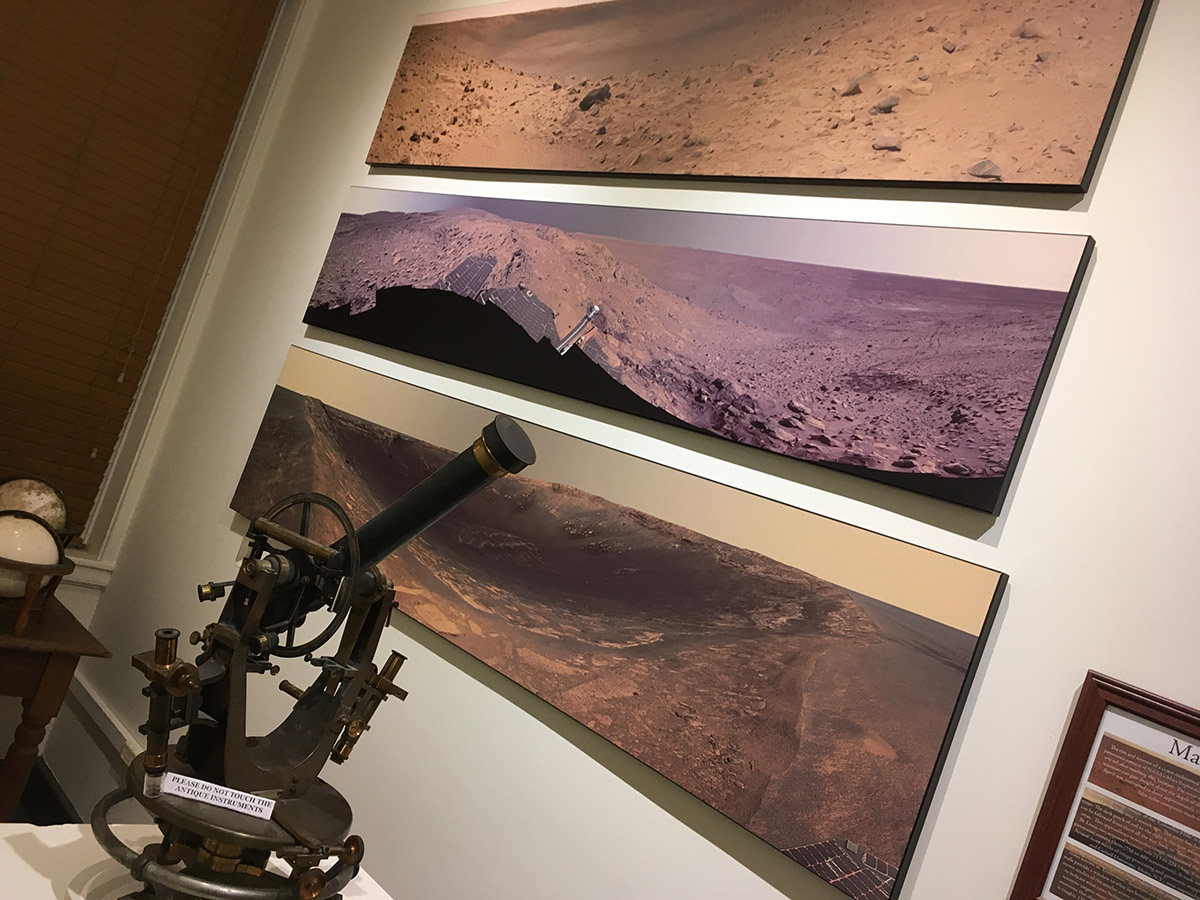

Thanks to the Cornell Astronomical Society, Cornell’s Fuertes Observatory has a new museum featuring vintage observatory instruments, many collected in the 19th century by Estevan Fuertes, founding dean of Cornell’s civil engineering department.

“This place has come alive. It used to be a storage facility. It’s no longer a storage closet with telescopes on top, this museum has a heartbeat,” said Rushaniya Fazliyeva ’18, an astronomical society member.

While visitors wait their turn to scan the universe on the observatory’s roof, down below they can admire the astronomical, engineering and surveying tools from yesteryear. Built in 1917, the observatory taught engineering students how to operate cutting-edge surveying tools. The observatory is open every Friday from 8 p.m. to midnight.

Several instruments sit on their original piers, heavy pillars that keep the instruments stable. One of the museum’s displays, the astronomical transit, built by Troughton and Simms (London), was a fundamental 19th-century instrument that measured a star’s passage across the local meridian to reckon time and longitude. On another pier sits a zenith telescope by Fauth & Co., Washington, D.C., complete with the glass from the famed Alvan Clark and Sons, likely purchased around 1891.

“Some instruments were a little dusty, others needed tender loving care,” said Mike Roman, Ph.D. ’15, who spearheaded efforts to restore most of the instruments when he was a graduate student. “We took a conservator’s approach to gently cleaning each piece, disassembling to remove the dirt and oxidized oils from the bearings, all while retaining the original finishes and patinas.”

For years, Cornell Astronomical Society members aimed to build a museum from its instrument collection. But plaster walls peeled, paint chipped, caulk disintegrated and glazing decayed.

Advocating for renovations, the students worked with Dave Pawelczyk, facility manager for the astronomy department, to secure much-needed repairs and restoration. “Dave shared our passion for improving the observatory – even when it meant more work for him,” said Roman.

Funds were limited and transforming the rooms into a museum required more money and work. Society member Brecken Blackburn '15 suggested crowdfunding. She teamed with Sam Newman-Stonebraker ’17, the society’s current president, to raise over $9,000. With funds in hand, the student designed the museum.

As the students worked on the instruments, Pawelcyzk got the building into shape by calling in Cornell’s electric, paint and carpenter shops. The new lighting, fresh paint and attention to detail, transformed the space.

On April 1, the society will launch a new fundraising campaign to renovate the observatory's office, dome and classroom.

Newman-Stonebraker said this building is Cornell’s fifth observatory. Three others, wooden structures, had been located on central campus and a fourth – from 1900 to 1913 – was located on the site of Barton Hall. That building featured special vertical slits in the north and south walls for the transit instruments and a so-called “computing room” to calculate observations. Cornell located its fifth observatory building at the current North Campus site in 1917.

Five years after dedication, the building obtained and housed the Irving Porter Church (a prominent Cornell Civil Engineering professor) 12-inch refracting telescope that still features its now-rare, original weight-driven mechanical clock-drive. Wound by hand once every 90 minutes while in use, the weights power a set of gears that turn the telescope at 15 degrees each hour on its equatorial axis.

Proud of the group’s long project, Newman-Stonebraker noted how the instruments are set up close to the same way they were a century ago. “This place has a fantastic history,” he said. “It’s back to the future.”

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe