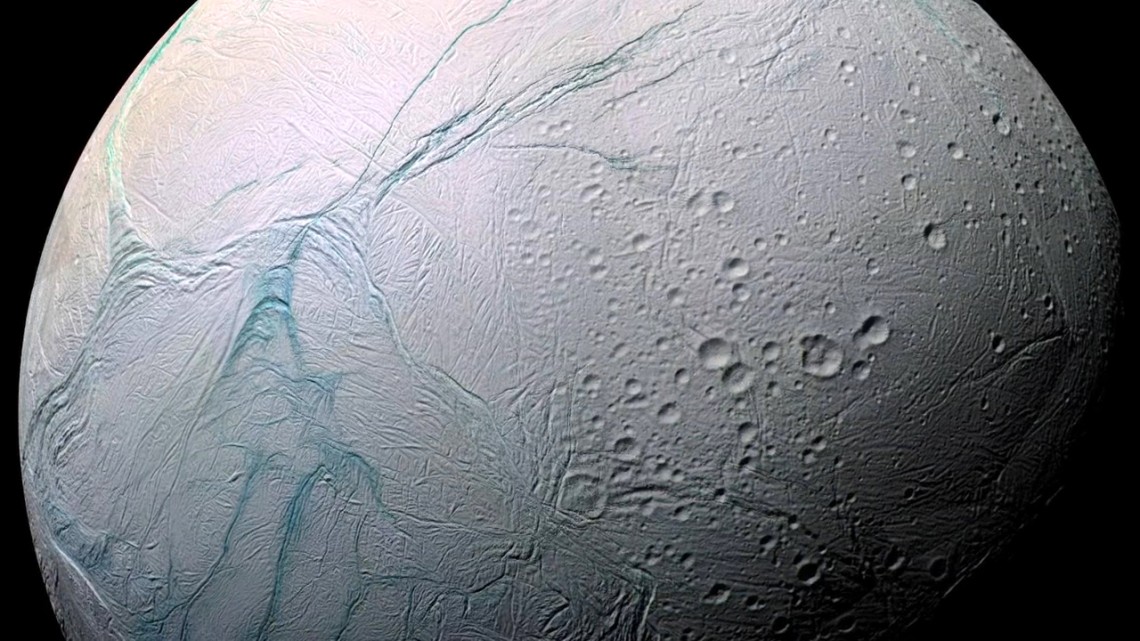

Saturn’s moon Enceladus.

Cornell played large scientific role on Cassini mission

By Blaine Friedlander

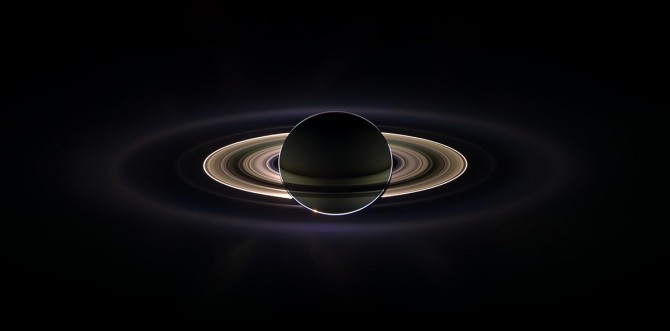

NASA is calling the Cassini mission’s last hurrah the Grand Finale. After cruising seven years to Saturn and spending 13 years strolling its neighborhood, on Sept. 15 the spacecraft ends its mission by plunging into the ringed planet’s atmosphere, breaking into fiery shards.

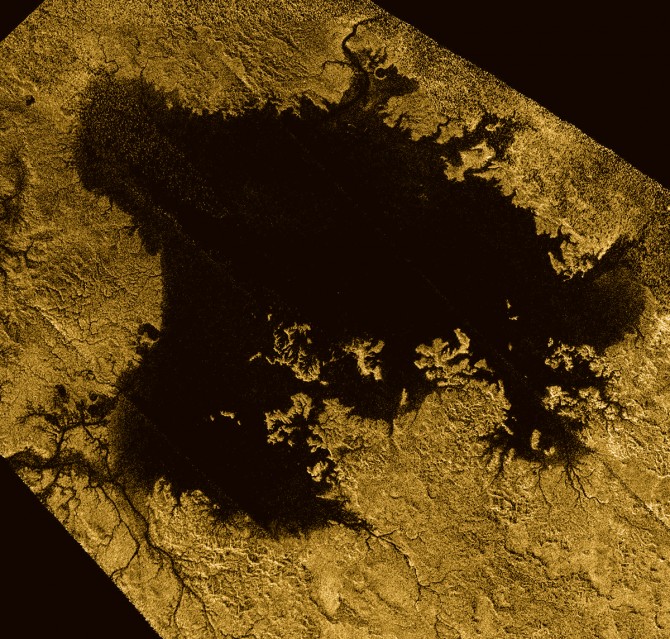

Cornell researchers helped bring the world Saturn in high resolution. Using the mission’s data, the scientists helped to analyze the rings, unveil the icy crust-covered oceans on the moon Enceladus, and divulge plastic “wrong way” dunes, “magic islands” and gnarly hydrocarbon waves on Saturn’s moon, Titan.

“We have had a remarkable history with Cassini. But one of the most remarkable aspects of the Cassini mission is its multigenerational nature,” said Alex Hayes ’03, M.Eng. ’04, assistant professor of astronomy. “There are at least five generations of scientists reflected in the Cassini science team.”

Cassini launched Oct. 15, 1997, and reached Saturn in June 2004. Dozens of professors, researchers and students worked on the craft’s imaging radar team, the imaging system camera, the visual and infrared mapping spectrometer and the composite infrared spectrometer. Joe Burns, Ph.D. ’66, the Irving Porter Church Professor of Engineering and professor of astronomy; Phil Nicholson, professor of astronomy; Jonathan Lunine, the David C. Duncan Professor in the Physical Sciences; Peter Gierasch, professor emeritus of astronomy; and Steve Squyres ’81, the James A Weeks Professor of Physical Sciences were among the early Cornell scientists on the mission.

Lunine explained that Cornell’s involvement with missions like Cassini attracts bright students. “The opportunity to make discoveries with Cassini data newly returned to Earth – as has happened multiple times – makes Cornell an irresistible place for the next generation of space talent,” he said.

During their time on campus, Roger Michaelides ’15 examined Titan’s carbon lake basins; Lea Bonnefoy ’15 wrote the algorithm that mapped Titan’s dunes; and Jason Hofgartner M.S. ’14, Ph.D. ’16, scrutinized Titan’s seas to find Magic Island.

And students continue to examine Cassini data. John Kelland ’18 inspects all images from Cassini’s infrared spectrometer, aiming to identify Titan’s tropospheric methane clouds. He analyzes characteristics of cloud sequences to understand Titan’s active methane cycle.

“Working with the Cassini data has been invaluable,” Kelland said. “It is a challenge to organize and analyze large datasets, all the while addressing new questions in planetary science.”

Cassini provided knowledge of uncharted territory in the solar system, but the mission’s legacy includes student-scientists. Hayes, who as a Cornell undergraduate gained extensive experience working on the Spirit and Opportunity Mars Exploration Rover missions, said: “Cassini provided a unique opportunity to inject students into large collaborations and expose them to new data where their ability – not their age or status – determined the level to which they became involved.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe