New book explores the meaning of being a human animal

By Linda B. Glaser

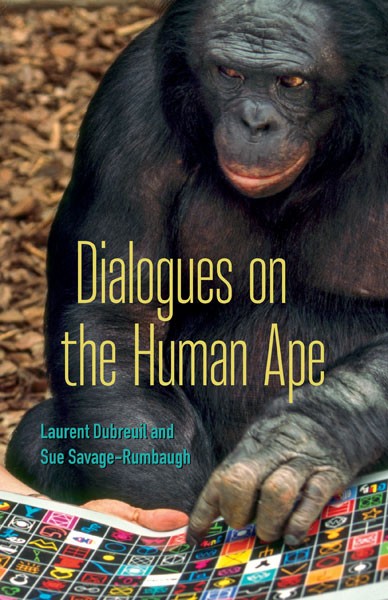

What does it mean to be a “human” animal? In conversations that roam over vast realms of human thought – from Descartes to Noam Chomsky, Socrates to Steven Wise – Cornell philosopher Laurent Dubreuil and primatologist Sue Savage-Rumbaugh explore the theoretical and practical dimensions of being human in their book, “Dialogues on the Human Ape” (2018, University of Minnesota Press).

The book explores the continuities between the ape and human minds, addressing why language matters to consciousness, free will and the formation of the self.

“The volume is conceived as an experimental work, written in collaboration by humans, with the help of bonobos. The horizon is a fresh take on the co-creation of truth and fiction within ‘humanness,’” writes Dubreuil, professor of Romance studies, comparative literature and cognitive science in the College of Arts and Sciences.

Humanness is often defined by the capacity for language and abstract thinking. But Savage-Rumbaugh found during decades of research with chimpanzees and bonobos that these animals can acquire human language through signing, the use of symbols and technology. The authors argue that being human is therefore not a fixed characteristic rooted in genetics or culture, but an epigenetically driven process.

“Humanness is neither the automatic consequence of a genetic profile nor a mere construction of ‘free-floating’ (and ‘unnatural’) cultures,” Dubreuil writes. “It is a possibility that cannot arise in any species; but, as a possibility, it is able to emerge in a priori ‘nonhumans’ [such as bonobos and chimpanzees].”

Savage-Rumbaugh’s language research with primates at Georgia State University, the Iowa Primate Learning Sanctuary and elsewhere incorporated computers and arbitrary symbols called lexigrams. A “spectacular” breakthrough came in 1985, Dubreuil writes in the introduction, “when Kanzi, a young male bonobo, spontaneously acquires an impressive command of lexigrams by attending the training sessions held by Savage-Rumbaugh and collaborators for his adoptive mother Matata.”

Savage-Rumbaugh focuses “on the role of culture as the driving force behind the behavioral changes and cognitive extensions that take place in the apes she works with,” Dubreuil writes. The success of her new paradigm of language learning, “made of immersion within symbolic culture and a constant use of language through both scripted and improvised life events,” was demonstrated by the bonobos’ comprehension of spoken English, on par with a human child, and their ability to understand and use hundreds of lexigrams. They also learned to vocalize sounds corresponding to English words, as well as to fabricate and use stone tools, count, make fires and draw self-portraits.

Language is “brought into existence by the process of dialogue embedded in real-life contexts and events,” Savage-Rumbaugh writes. “Kanzi spoke because there were real things to speak about and people to speak with (the dogs that appeared in the forest, the rain, the fire in the play-yard, the visitors, etc.). It was this process that rendered the bonobo’s language capacities so like our own. … They were becoming truly human, exquisitely human, morally human and philosophically human.”

Among Dubreuil’s other books are “The Intellective Space,” “Poetry and Mind” and the just released “La dictature des identités” (“Identity Dictatorship”).

Linda B. Glaser is a staff writer for the College of Arts & Sciences.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe