For hall of famers Jennings and Evans, baseball diamonds are forever

By Blaine Friedlander

On their way home from playing the Yankees in New York, the Cleveland Indians made a slight detour and stopped by Cornell’s Hoy Field on May 16, 1934, to play against the Big Red baseball team in front of 4,000 fans.

Legendary pitcher Walter Johnson, at the time the Indians’ field manager, pitched five innings, batted four times and scored a run in the exhibition. The Indians beat Cornell, 11-4.

Cleveland’s owners Alva Bradley (Class of 1907) and Charles Bradley (Class of 1908), and the team’s general manager, Billy Evans (Law, Class of 1905), had brought the team to Ithaca as a public relations gambit.

The Cornell Daily Sun reported that Johnson, who had grown up on a farm, admired the beauty of the campus and seemed impressed with the agriculture college. Prior to the game, the Cleveland Press said the Indians’ players asked about the university’s colors. When told Cornell’s was red, catcher and right fielder Glenn Myatt quipped: “They can’t have red. That’s our color. All Billy Evans does all winter is write and tell us our team is in the red.”

Evans is one of two Cornellians – the other is Hughie Jennings, Class of 1904, also a law alumnus – who have been inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

Evans (inducted as an umpire in 1973) served as the Indians’ general manager from 1928-35, the first of several jobs he held later as a baseball executive.

Evans left Cornell early to support his family after his father died. He became a journalist at the Youngstown Vindicator, in his hometown, rising to become sports editor and covering the Penn-Ohio Class D team there. One Saturday, an umpire failed to show. The field managers asked Evans to officiate the game, but Evans – wearing his best suit for a date later that night – refused. He refused, that is, until the managers mentioned the $15 umpire fee. Evans agreed.

Shortly afterward, Evans became a major league umpire at age 22, earning the nickname “The Boy Umpire.”

Over his career, Evans was an ump in six World Series. His first, in 1909, was between the Pittsburgh Pirates and the Detroit Tigers. Detroit’s manager was Jennings, Evans’ Cornell coach.

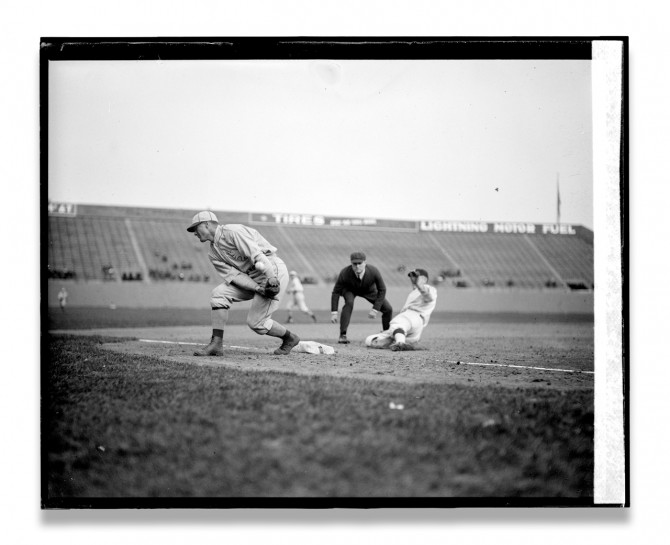

Evans was well known for proficiency and professionalism. On Sept. 24, 1921, the second division Detroit Tigers played the mediocre Washington Senators. Fiery Tiger Ty Cobb, at the time a player-manager, singled in the fifth inning and tried to steal second base. Evans called him out. Cobb disagreed.

After the game, Cobb challenged Evans to a fight. Cobb did not know Evans had boxed at Cornell. Their brawl, under the stands at Washington’s Griffith Stadium, was described by one witness as the bloodiest ever seen in baseball. Some accounts called the fight a draw, while others said Cobb had the advantage.

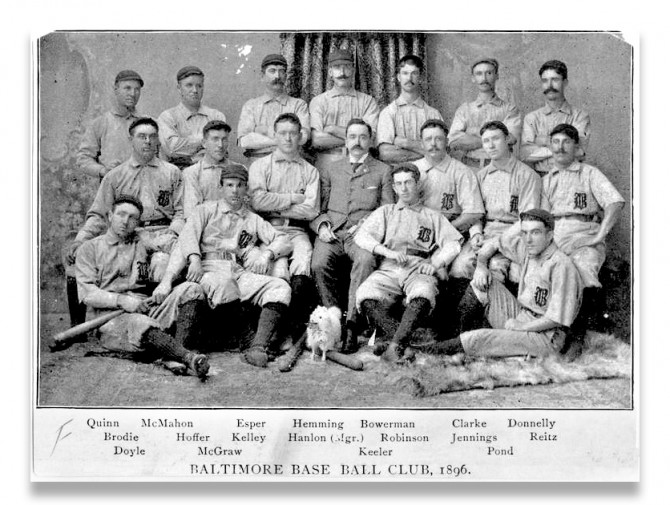

Before Hughie Jennings (inducted in 1945) arrived at Cornell to study law and coach the Big Red baseball team (64-61-1), he had a celebrated playing career as shortstop for the National League’s notoriously good Baltimore Orioles – a team that arguably gave rise to modern-era play.

With their aggressive hit-and-run and Baltimore Chop-style of play, the Orioles finished in first place three years in a row. Jennings’ batting average soared to .335 in 1894, .386 in 1895 (204 hits, scoring 159 runs) and a team-leading .401 (209 hits, stealing 70 bases) in 1896, while driving in 121 runs.

With his baseball skills diminishing, however, Jennings enrolled at Cornell and left the university in 1904, two semesters shy of a bachelor’s degree. He passed the Maryland and Pennsylvania bars, but the Detroit Tigers hired him in 1907 to manage their team. Under Jennings, the Tigers played in three consecutive World Series.

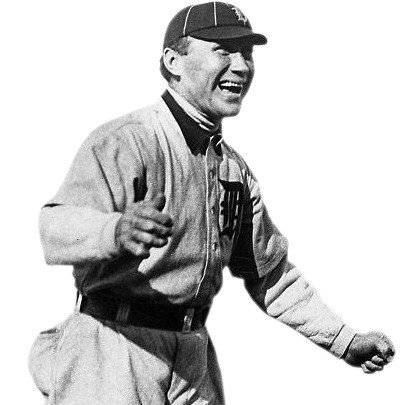

Jennings became proficient as a dugout psychologist, bringing out the best in his players. Often, he tried to distract opposing teams with his dancing, third-base coaching box antics and his signature, echoing cry of “Ee-Yah!” through a grin.

Those “Ee-Yah” roars soon became part of the American lexicon, as kids often shouted it out and soldiers later used it as a battle yell in World War I.

Biographer Jack Smiles noted that Jennings’ off-season law practice thrived in Scranton, Pennsylvania. In the winters and during Christmas season, Jennings would obtain lists of destitute families from local churches to bring care packages of food and clothing. He taxied coal miners to work, secretly aided impoverished old ballplayers and, in the spring, taught children the game of baseball.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe