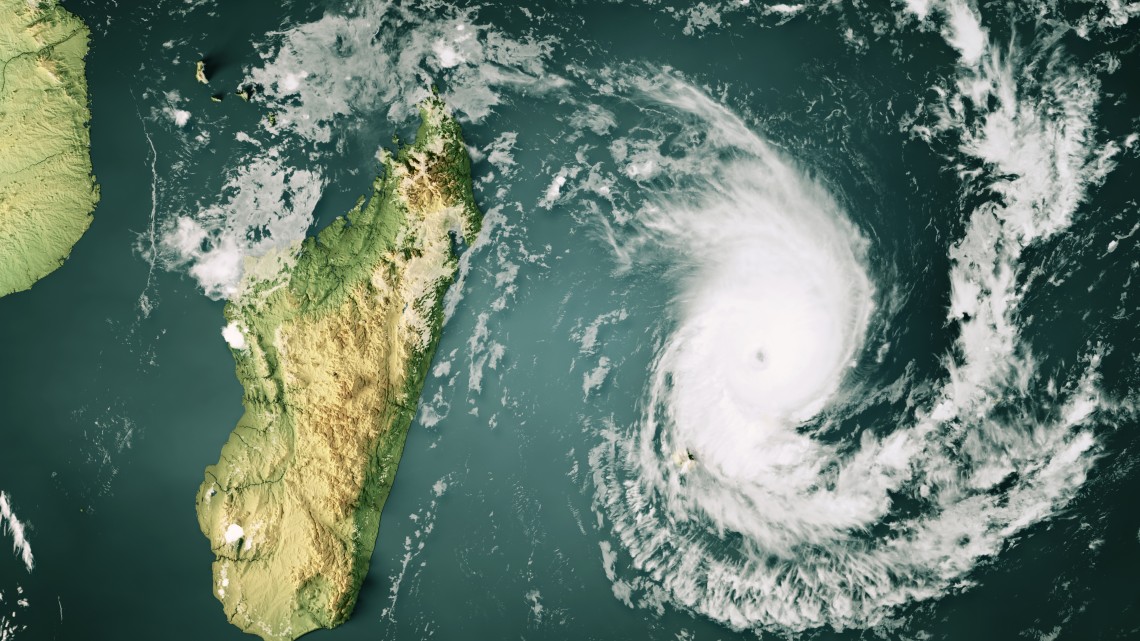

In March of 2023, Tropical Cyclone Freddy, the most powerful cyclone ever recorded, slammed the East Coast of Africa hitting Malawi the hardest. Cornell experts are advocating for global policy that recognizes the role for communities in climate adaptation and mitigation.

News directly from Cornell's colleges and centers

Cornellian UN climate authors warn of ‘extreme’ risk to people, food systems

By Krisy Gashler

When Tropical Cyclone Freddy battered East Africa this spring, it became the longest-lasting, most powerful cyclone ever recorded worldwide. It killed almost 1,500 people, 1,216 of them in Malawi. For decades, scientists have warned that the increased frequency and intensity of storms and other natural disasters are directly linked to climate change.

“Places like Malawi are highly vulnerable to climate impacts but bear virtually no responsibility in terms of greenhouse gas emissions,” said Rachel Bezner Kerr, a Cornell Atkinson faculty fellow, professor in the Department of Global Development in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences (CALS), and one of the coordinating lead authors of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) Working Group II report on Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability.

For Bezner Kerr, Tropical Cyclone Freddy was not just another data point: She has conducted collaborative research in Malawi for over 20 years, seeking to improve small-scale farm families’ food security, nutrition, income and sustainable land use. Two of her friends were killed in flooding in Malawi this spring.

“I hope that the severity of the message coming out of the assessment of the scientific literature is an alarm bell for policymakers to understand how much responsibility they have and how crucial it is that they take action,” she said.

Bezner Kerr is one of several Cornellians who are playing critical roles in establishing the scientific basis upon which global citizens and leaders can understand the causes, effects and solutions to climate change. This week, world leaders are meeting in Bonn, Germany, for the United Nations’ Bonn Climate Change Conference; The annual spring conference convenes those leaders, along with environmental organizations, businesses, scientists and others, to continue negotiations in preparation for the larger Conference of the Parties (COP) gatherings each fall. This year, world leaders are completing the first-ever Global Stocktake: A key element of the 2015 Paris Agreement, the Stocktake compels countries to share data on how, or if, they have implemented the promises they made when signing the 2015 Paris Agreement.

UN-university partnerships build adaptation capacity

Allison Chatrchyan, senior research associate in CALS’ Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences and adjunct professor of international environmental law at the Cornell Law School, is participating as a party negotiator at the Bonn conference this week. She is also co-presenting at a United Nations side event on the U.N. Climate Change and Universities Partnership Program (UN-UPP), along with Deborah Aller, extension associate in CALS’ School of Integrative Plant Science, and three students who have worked on partnership projects: Anna Connor, MRP ’23, Chloe Long, MRP ’25, and Maria Anaya Torres, Cornell Law School, JSD ’25.

The moderated discussion on the power of the UN-UPP to build capacity for climate adaptation globally will be broadcast live June 10 at 10:45 a.m. EDT. Chatrchyan has been bringing Cornell students to COP meetings as part of her Global Climate Change Science and Policy course since 2017.

“In my courses, we focus on the concept of polycentric climate governance: the idea that meeting the goals of the Paris Agreement is not only the mandate of nation states, but is very importantly driven by nongovernmental organizations and civil society,” Chatrchyan said. “It gives me hope to see the level of skill and fervor that these students bring to their engagement with international partners, and their commitment to combating climate change.”

Extreme changes more likely with each increment of warming

Natalie Mahowald, the Irving Porter Church Professor in Engineering in the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, has also been involved in IPCC scientific assessments. She participated as a lead author of the IPCC’s Working Group I report, Climate Change 2014: The Physical Science Basis, and as lead author of the 2018 IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 C. Currently, Earth’s global mean temperature is about 1 degree Celsius above pre-industrial temperatures. The Paris Agreement calls for limiting that increase to 2 C, and preferably 1.5 C.

“The small island and developing states have argued that we need to work harder to reach lower climate targets, leading to the request to write a report focused on reaching 1.5 degrees,” Mahowald said. “Because the difference in outcomes between 1.5 and 2 are important; projected changes in extremes are larger in frequency and intensity with every additional increment of global warming.”

Karl Hausker ’79, a senior fellow at the World Resources Institute, served as an Expert Reviewer for the IPCC Working Group III report, Mitigation of Climate Change. Hausker noted that while the full Working Group reports are authored by scientists and experts, the accompanying summaries for policymakers require approval of governments, and critical elements can be removed or watered down to appease certain countries. For example, the summary of his working group’s report removed almost every mention of nuclear energy, despite it playing a significant role in providing zero-carbon electricity in most of the global mitigation scenarios, he said.

“Some countries are expanding nuclear power, while others are phasing it out,” Hausker said. “But it’s a bit like whack-a-mole. If you take any of these solutions off the table, or constrain them, you’ve got to do more of something else.”

Krisy Gashler is a freelance writer for Cornell Atkinson.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe