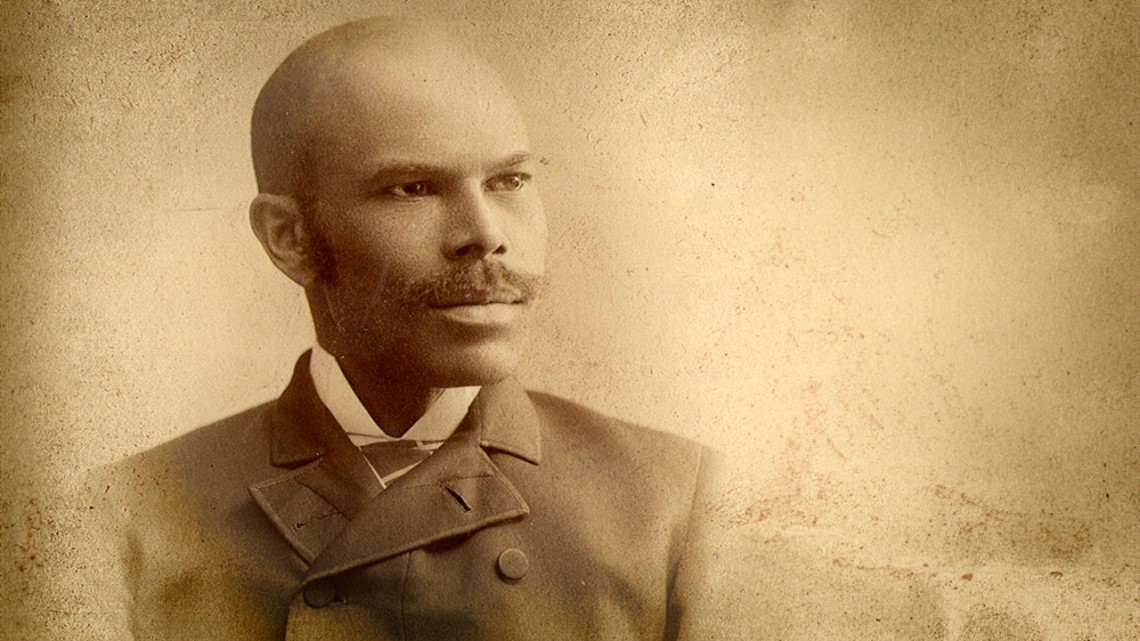

George W. Fields, shown here in his class photo from 1890, was Cornell Law School’s first Black American graduate and one of the first three Black Americans to graduate from the university.

Performance, book honor first Black American law graduate

By Susan Kelley, Cornell Chronicle

A stray Yankee shell hit the cabin porch just feet from where 9-year-old George Washington Fields and his family watched Union forces overpower Confederate troops at the plantation where the Fieldses were enslaved, in Hanover County, Virginia, in 1863.

Fields’ mother saw her chance, and took it.

Martha Ann Fields gathered her family’s meager belongings and fled with six of her children, traveling 90 miles by foot, dugout canoe, wagon and barge to the safety of Union-held territory. She urged them on, repeating “Come on, children.”

That’s the title of a newly published autobiography by George W. Fields, Class of 1890, who would go on to become Cornell Law School’s first Black American graduate. He was one of the first three Black Americans to graduate from Cornell and the only formerly enslaved person to get a degree from the university. (While there were Black students in the 1870s, most were from Cuba and the Caribbean.)

The Law School will host a dramatic reenactment of the family’s escape to freedom, performed by a Fields descendant and a genealogical researcher, to celebrate the launch of Fields’ autobiography. “Come on, Children: The Autobiography of George Washington Fields, Born a Slave in Hanover County, Virginia,” was edited by Kevin Clermont, the Robert D. Ziff Professor of Law at Cornell Law School. The event, “Flight to Freedom: The Fields Family and Freedom’s Fortress,” will take place on Feb. 12, noon to 1 p.m., in Myron Taylor Hall.

“While it seemed like their agency or self-determination was limited, they played an active role in determining their lives as much as they could, even during enslavement and the Civil War,” said Ajena Cason Rogers, Fields’ great-great-grand niece and a historical interpreter with the National Park Service. Her family kept stories alive about George Fields’ brother, James, who escaped enslavement before the family did and became a spy for the Union forces.

She hopes the performance will help people feel the sense of family and faith that has been passed down to the descendants today, she said. “My grandmother would tell us these stories as kids to keep us inspired to keep striving. It wasn’t that long ago and those things that happened are still affecting us now.”

Rogers and Drusilla Pair, a genealogical researcher specializing in the James Fields family, began creating the theatrical art piece in 2012. “We wanted to do something that was not just a PowerPoint lecture,” Pair said. They based the script on oral histories, documents including family bibles and grave markers, spiritual songs and the autobiography, which Fields wrote about 50 years after the Civil War.

They and Clermont discovered Fields’ manuscript at about the same time, after having researched Fields’ story independently for years. Separately, Pair and Clermont both found footnotes in other books referencing the manuscript and tracked it down at the Hampton (Va.) History Museum.

Rogers said the account is gripping. “I remember specifically sitting there reading and going, ‘Well, what happens next? How does he get away? How does he do it?’ And then, of course he got away, or else I wouldn’t be sitting here reading it if he hadn’t,” Rogers said.

For Clermont, discovering the manuscript meant a breakthrough to the mystery of how Fields got from being an enslaved person to applying to Cornell Law School 24 years later. “And seeing that footnote that there was an unpublished autobiography, I thought, ‘Oh, my gosh, I can answer all these questions,’” Clermont said.

The book is a reworking of Clermont’s previous book, “The Indomitable George Washington Fields: From Slave to Attorney,” published in 2013.

In the autobiography, Fields describes how he saw his mother whipped until she collapsed for not cooking a game bird to her mistress’s liking. As a young child, he hoed corn and fetched water for field slaves all day alongside grown men. He carried his sister, Catherine, who was too young to walk, on their 90-mile journey to freedom.

Fields later worked to support his family and got an excellent education at the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, now known as Hampton University, founded after the Civil War to provide education to freedmen. He went north and worked for nearly a decade before earning his law degree at age 36.

Fields had planned on going to Yale University. But he worked for a time as a butler for Alonzo Cornell, Ezra Cornell’s eldest son and governor of New York, who convinced him to go to Cornell – even though it did not yet have a Law School. The autobiography ends as Fields enters the inaugural class of the new Law School, in 1887.

The new book includes an editor’s note describing how Clermont happened upon Fields’ senior thesis at the Law School. Copious footnotes give background information. One footnote describes how the battle at the plantation, Clermont’s research found, was part of a larger Union effort to wreck the intersecting railroads in Hanover County.

An epilogue describes Fields’ life after graduating. “He was then a leading lawyer in Hampton, Virginia. You can just see that he was an excellent lawyer,” Clermont said.

Fields also became a well-known a community leader despite having been blinded in a fishing accident. “But he overcame that too,” Clermont said. “This guy – heroic is the only word for him. Most significant is this incredible courage he had, to keep going and to overcome obstacles. In a sense, it’s a good message for the Law School students.”

Pair too hopes people will see that Fields’ story can inspire us today.

“The Fields family’s issue was overcoming slavery. But every human being has something that they have to overcome, something that is oppressing them, whether it’s internal or external forces,” she said. “And the Fields took the opportunity to overcome enslavement and not wait for somebody to give that opportunity to them. And we should all do that with whatever we’re grappling with: Do something about it.”

Media Contact

Damien Sharp

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe