'Cornell dots' make the world's tiniest laser

By Bill Steele

Researchers have modified nanoparticles known as "Cornell dots" to make the world's tiniest laser -- so small it could be incorporated into microchips to serve as a light source for photonic circuits. The device may also have applications for sensors, solar collectors and in biomedicine.

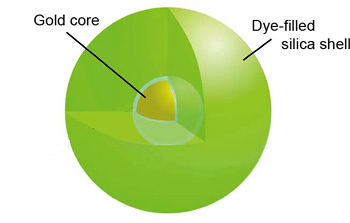

The original Cornell dots, created by Ulrich Wiesner, the Spencer T. Olin Professor of Engineering at Cornell, consist of a core of dye molecules enclosed in a silica shell to create an unusually luminous particle. The new work by researchers at Norfolk (Virginia) State University (NSU), Purdue University and Cornell uses what Wiesner calls "hybrid Cornell dots," which have a gold core surrounded by a silica shell in which dye molecules are embedded.

The research is reported in the Aug. 16 online issue of the journal Nature and will appear in a coming print issue.

Using nanoparticles 44 nanometers (nm -- one billionth of a meter or about three atoms in a row) wide, the device is the smallest nanolaser reported to date, and the first operating in visible light wavelengths, the researchers said.

"This opens an interesting playground in terms of miniaturization," said Wiesner. "For the first time we have a building block a factor of 10 smaller than the wavelength of light."

An optical laser this small is impossible because a laser develops its power by bouncing light back and forth in a tuned cavity whose length must be at least half the wavelength of the light to be emitted. In the first tests of the new device, the light emitted had a wavelength of 531 nm, in the green portion of the visible spectrum.

In a conventional laser, molecules are excited by an outside source of energy, which may be light, electricity or a chemical reaction. Some molecules spontaneously release their energy as photons of light, which bounce back and forth between two reflectors, in turn triggering more molecules to emit photons.

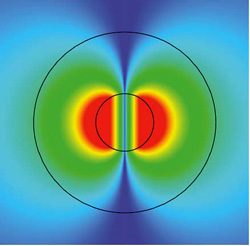

In the new device, dye molecules in the nanoparticle are excited by a pumping laser. A few molecules spontaneously release their added energy to generate a plasmon -- a wave motion of free electrons at an optical frequency -- in the gold core. In the tiny space, the dye molecules and the gold core are coupled by electric fields, explains Purdue co-author Vladimir Shalaev.

Oscillations of the plasmon in turn trigger more dye molecules to release their energy, which further pumps up the plasmon, creating a "spaser" (surface plasmon amplification by stimulated emission of radiation). When the energy of the system reaches a threshold the electric field collapses, releasing its energy as a photon. The size of the core -- 14 nm in diameter -- is chosen to set up a resonance that reinforces a wave corresponding to the desired 531 nm light output.

Tests at NSU indicate that the lasing effect occurs within each Cornell dot and is not a phenomenon of a collection of the nanoparticles working together, making this unquestionably the world's smallest laser.

"Some people argue that the ability to produce a surface plasmon in this way will be even more useful," added NSU professor and lead author Mikhail Noginov. It has been suggested that plasmons could be used to send signals across a microchip at the speed of light -- much faster than electrons in wires -- but in less space than photonic circuits need.

The idea of a spaser was first proposed in 2003 by physicists Mark Stockman at Georgia State University and David Bergman at Tel Aviv University. The theory behind the new approach was developed by Evgenii Narimanov at Purdue.

The work is funded by the National Science Foundation, with additional funding from the U.S. Army Research Office.

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe