'Cornell Dots' that light up cancer cells go into clinical trials

By Bill Steele

"Cornell Dots" -- brightly glowing nanoparticles -- may soon be used to light up cancer cells to aid in diagnosing and treating cancer. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the first clinical trial in humans of the new technology. It is the first time the FDA has approved using an inorganic material in the same fashion as a drug in humans.

"The FDA approval finally puts a federal approval stamp on all the assumptions we have been working under for years. This is really, really nice," said Ulrich Wiesner, the Spencer T. Olin Professor of Materials Science and Engineering, who has devoted eight years of research to developing the nanoparticles. "Cancer is a terrible disease, and my family has a long history of it. I, thus, have a particular personal motivation to work in this area."

The trial with five melanoma patients at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in New York City will seek to verify that the dots, also known as C dots, are safe and effective in humans, and to provide data to guide future applications. "This is the first product of its kind. We want to make sure it does what we expect it to do," said Michelle Bradbury, M.D., radiologist at MSKCC and assistant professor of radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College.

C dots are silica spheres less than 8 nanometers in diameter that enclose several dye molecules. (A nanometer is one-billionth of a meter, about the length of three atoms in a row.) The silica shell, essentially glass, is chemically inert and small enough to pass through the body and out in the urine. For clinical applications, the dots are coated with polyethylene glycol so the body will not recognize them as foreign substances.

To make the dots stick to tumor cells, organic molecules that bind to tumor surfaces or even specific locations within tumors can be attached to the shell. When exposed to near-infrared light, the dots fluoresce much brighter than unencapsulated dye to serve as a beacon to identify the target cells. The technology, the researchers say, can show the extent of a tumor's blood vessels, cell death, treatment response and invasive or metastatic spread to lymph nodes and distant organs. The safety and ability to be cleared from the body by the kidneys has been confirmed by studies in mice at MSKCC, reported in the January 2009 issue of the journal Nano Letters (Vol. 9 No. 1).

For the human trials, the dots will be labeled with radioactive iodine, which makes them visible in PET scans to show how many dots are taken up by tumors and where else in the body they go and for how long.

"We do expect it to go to other organs," Bradbury said. "We get numbers, and from that curve derive how much dose each organ gets. And we need to find out how fast it passes through. Are they cleared from the kidney at the same rate as in mice?"

One of many advantages of C dots, Bradbury noted, is that they remain in the body long enough for surgery to be completed. "Surgeons love optical," she said. "They don't need the radioactivity, but [our study] confirms what the optical signal is. As you learn that, eventually you no longer need the radioactivity."

On the other hand, she added, the dots also may serve as a carrier to deliver radioactivity or drugs to tumors. "This is step one to jump-start a process we think will do multiple things with one platform," she said.

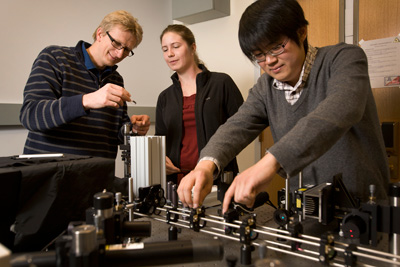

First-generation Cornell dots were developed in 2005 by Hooisweng Ow, then a graduate student working with Wiesner. Wiesner, Ow and Kenneth Wang '77 have co-founded the company Hybrid Silica Technologies to commercialize the invention. The dots, Wiesner said, also have possible applications in displays, optical computing, sensors and such microarrays as DNA chips.

Wiesner's original research was funded by the National Science Foundation, New York state and Phillip Morris USA.

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe