Portable device will quickly detect pathogens in developing countries

By Bill Steele

Two Cornell professors will combine their inventions to develop a handheld pathogen detector that will give health care workers in the developing world speedy results to identify in the field such pathogens as tuberculosis, chlamydia, gonorrhea and HIV.

Using synthetic DNA, Dan Luo, professor of biological and environmental engineering, has devised a method of "amplifying" very small samples of pathogen DNA, RNA or proteins. Edwin Kan, professor of electrical and computer engineering, has designed a computer chip that quickly responds to the amplified samples targeted by Luo's method. They will combine these to make a handheld device, usable under harsh field conditions, that can report in about 30 minutes what would ordinarily require transporting samples to a laboratory and waiting days for results.

The work will be supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation as part of the Grand Challenge program to develop "point-of-care diagnostics" for developing countries. The foundation has distributed $25 million to 12 teams, selected from more than 700 applicants. Various teams are working on different aspects of the technology, and eventually their work will be integrated to make a practical, low-cost testing kit, Luo said.

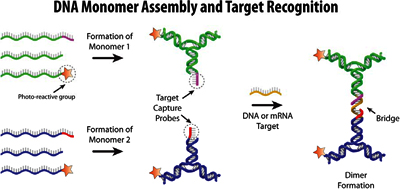

Luo's research group has found that DNA can be used like molecular-level Lego blocks. A single strand of DNA will lock onto another single strand that has a complementary genetic code. By synthesizing DNA strands that match over just part of their length, his team can assemble unusual shapes -- in this case, a Y. Attached to the base of the Y is a DNA strand or antibody designed to lock onto a pathogen. Attached to one of the upper arms is a molecule that will polymerize -- chain up with other similar molecules -- when exposed to ultraviolet light.

When a pathogen is added to a solution of these Y-DNA molecules, the matching receptors on the stem of the Y will lock onto pathogen molecules, but only onto part of them; the mix will contain two different Y-structures, each tagged to lock onto a different part of the pathogen molecule. The result, when the targeted pathogen is present, is the formation of many double-Ys linked together by a pathogen molecule, each assembly carrying two molecules capable of polymerizing.

When the mixture is exposed to a portable ultraviolet light, the polymer molecules at the ends of each double-Y link to those on other double-Ys, forming long chains that clump up into larger masses. This polymerization won't happen, the researchers emphasize, unless a targeted pathogen is present to link two Ys together. A single Y with only one polymer molecule attached can only link to one other single Y, and no chain will form.

Kan's new chip measures both the mass and charge of molecules that fall on it. The large clumps of Y-DNA have a much larger mass and charge than single molecules, and trigger the detector. The chip uses the popular and inexpensive CMOS technology compatible with other common electronic devices. A detector might, for example, be controlled and powered by a mobile phone, Luo suggested.

All this can be combined with nanofluidics to make a robust battery-operated testing kit, the researchers said. After further development they plan to conduct tests simulating field conditions in the developing world. Along with surviving hot or cold weather, Luo said, "It has to work in dirty water."

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe