Student designer and fiber scientists create a dress that prevents colds and a jacket that destroys noxious gases

By Anne Ju

Fashion designers and fiber scientists at Cornell have taken "functional clothing" to a whole new level. They have designed a garment that can prevent colds and flu and never needs washing, and another that destroys harmful gases and protects the wearer from smog and air pollution.

The two-toned gold dress and metallic denim jacket, featured at the April 21 Cornell Design League fashion show, contain cotton fabrics coated with nanoparticles that give them functional qualities never before seen in the fashion world.

Designed by Olivia Ong '07 in the College of Human Ecology's Department of Fiber Science and Apparel Design, the garments were infused with their unusual qualities by fiber science assistant professor Juan Hinestroza and his postdoctoral researcher Hong Dong. Apparel design assistant professor Van Dyke Lewis launched the collaboration by introducing Ong to Hinestroza several months ago.

"We think this is one of the first times that nanotechnology has entered the fashion world," Hinestroza said. He noted one drawback may be the garments' price: one square yard of nano-treated cotton would cost about $10,000.

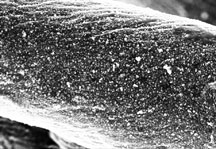

Ong's dress and jacket, part of her original fashion line called "Glitterati," look innocently hip. But closer inspection -- with a microscope, that is -- shows an army of electrostatically charged nanoparticles creating a protective shield around the cotton fibers in the top part of the dress, and the sleeves, hood and pockets of the jacket.

"It's something really moving toward the future, and really advanced," said Ong, who graduates in December and aspires to design school. "I thought this could potentially be what fashion is moving toward."

Dong explained that the fabrics were created by dipping them in solutions containing nanoparticles synthesized in Hinestroza's lab. The resultant colors are not the product of dyes, but rather, reflections of manipulation of particle size or arrangement.

The upper portion of the dress contains cotton coated with silver nanoparticles. Dong first created positively charged cotton fibers using ammonium- and epoxy-based reactions, inducing positive ionization. The silver particles, about 10-20 nanometers across (a nanometer is one-billionth of a meter) were synthesized in citric acid, which prevented nanoparticle agglomeration.

Dipping the positively charged cotton into the negatively charged silver nanoparticle solution resulted in the particles clinging to the cotton fibers.

Silver possesses natural antibacterial qualities that are strengthened at the nanoscale, thus giving Ong's dress the ability to deactivate many harmful bacteria and viruses. The silver infusion also reduces the need to wash the garment, since it destroys bacteria, and the small size of the particles prevents soiling and stains.

The denim jacket includes a hood, sleeves and pockets with soft, gray tweed cotton embedded with palladium nanoparticles, about 5-10 nanometers in length. To create the material, Dong placed negatively charged palladium crystals onto positively charged cotton fibers.

Ong, though strictly a designer, was drawn especially to the science behind creating the anti-smog jacket.

"I thought it would be cool if [wearers] could wipe their hands on their sleeves or pockets," Ong said.

Ong incorporated the resultant cotton fiber into a jacket with the ability to oxidize smog. Such properties would be useful for someone with allergies, or for protecting themselves from harmful gases in the contaminated air, such as in a crowded or polluted city.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe