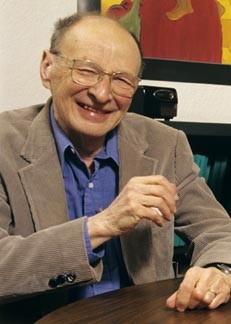

Urie Bronfenbrenner, father of Head Start program and pre-eminent 'human ecologist,' dies at age 88

By Susan S. Lang

Urie Bronfenbrenner, a co-founder of the national Head Start program and widely regarded as one of the world's leading scholars in developmental psychology, child-rearing and human ecology – the interdisciplinary domain he created – died at his home in Ithaca, N.Y., Sept. 25 due to complications from diabetes. He was 88.

At his death, Bronfenbrenner was the Jacob Gould Schurman Professor Emeritus of Human Development and of Psychology at Cornell University, where he spent most of his professional career. A memorial service organized by his family is planned for Saturday, Oct. 8, at 3 p.m. in Anabel Taylor Hall auditorium. A service for the Cornell community will be announced at a later time.

Bronfenbrenner's ideas and his ability to translate them into operational research models and effective social policies spurred the creation in 1965 of Head Start, the federal child development program for low-income children and their families. In 1979 Bronfenbrenner further developed his thinking into the groundbreaking theory on the ecology of human development. That theoretical model transformed the way many social and behavioral scientists approached the study of human beings and their environments. It led to new directions in basic research and to applications in the design of programs and policies affecting the well-being of children and families both in the United States and abroad.

His research also furthered the goals of Cornell's Life Course Institute, which was renamed the Bronfenbrenner Life Course Institute in 1993 and is currently directed by Daniel Lichter.

He spent many of his later years warning that the process that makes human beings human is breaking down as disruptive trends in American society produce ever more chaos in the lives of America's children. "The hectic pace of modern life poses a threat to our children second only to poverty and unemployment," he said. "We are depriving millions of children – and thereby our country – of their birthright … virtues, such as honesty, responsibility, integrity and compassion."

The gravity of the crisis, he warned, threatens the competence and character of the next generation of adults – those destined to be the first leaders of the 21st century. "The signs of this breakdown are all around us in the ever growing rates of alienation, apathy, rebellion, delinquency and violence among American youth," he said. Yet, Bronfenbrenner added: "It is still possible to avoid that fate. We now know what it takes to enable families to work the magic that only they can perform. The question is, are we willing to make the sacrifices and the investment necessary to enable them to do so?"

Bronfenbrenner also was well-known for his cross-cultural studies on families and their support systems and on human development and the status of children. He was the author, co-author or editor of more than 300 articles and chapters and 14 books, most notably "Two Worlds of Childhood: U.S. and U.S.S.R.," "The State of Americans," "The Ecology of Human Development" and "Making Human Beings Human." His writings were widely translated, and his students and colleagues number among today's most internationally influential developmental psychologists.

Researchers say that before Bronfenbrenner, child psychologists studied the child, sociologists examined the family, anthropologists the society, economists the economic framework of the times and political scientists the structure. As the result of Bronfenbrenner's groundbreaking concept of the ecology of human development, these environments – from the family to economic and political structures – were viewed as part of the life course, embracing both childhood and adulthood.

Bronfenbrenner's "bioecological" approach to human development shattered barriers among the social sciences and forged bridges among the disciplines that have allowed findings to emerge about which key elements in the larger social structure and across societies are vital for developing the potential of human nature. The theory has helped tease out what is needed for the understanding of what makes human beings human.

Stephen Ceci, professor of human development in the College of Human Ecology at Cornell who worked closely with Bronfenbrenner for almost 25 years, said: "When I first came to Cornell as a junior faculty member, I was pretty full of myself. I remember thinking that I was going to teach this old codger some new tricks and some new science. Little did I realize that once I began working with Urie the tables would be turned on me. I quickly apprehended that I was dealing with a true master, someone peerless. I doubt I taught Urie much, but I can attest to the fact that he taught me a great deal, including to think in ways that were new and exciting. Some of my best work was done at his instigation. My bioecological theory was a direct result of his enormous influence on my thinking."

He continued: "This year I received the James McKeen Catell Award from the American Psychological Society, the same award that Urie received many years earlier. At the award ceremony in Los Angeles, I commented that the award was the direct result of the good luck I had early in my career when I began collaborating with Urie. It is no exaggeration to say that he was the most important intellectual and personal mentor in my life. We will all miss him deeply."

Melvin L. Kohn, a professor of sociology at Johns Hopkins University who studied under Bronfenbrenner some 40 years ago, observed that "Urie was the quintessential person for spurring psychologists to look up and realize that interpersonal relationships, even the smallest level of the child and the parent-child relationship, did not exist in a social vacuum but were embedded in the larger social structures of community, society, economics and politics, while encouraging sociologists to look down to see what people were doing."

From the very beginning of his scholarly work, Bronfenbrenner pursued three mutually reinforcing themes: developing theory and corresponding research designs at the frontiers of developmental science; laying out the implications and applications of developmental theory and research for policy and practice; and communicating – through articles, lectures and discussions -- the findings of developmental research to undergraduate students, the general public and to decision-makers, both in the private and public sectors.

His widely published contributions won him honors and awards both at home and abroad. He held many honorary doctoral degrees, several of them from leading European universities. His most recent American award (1996), now given annually in his name, is for "Lifetime Contribution to Developmental Psychology in the Service of Science and Society" from the American Psychological Association, known as "The Bronfenbrenner Award."

"As the father of the Head Start program and a lifelong advocate for children and families, Urie Bronfenbrenner earned the acclaim of scholars and elected leaders alike for his insights and his commitment," said Cornell President Hunter R. Rawlings. "Perhaps more than any other single individual, Urie Bronfenbrenner changed America's approach to child rearing and created a new interdisciplinary scholarly field, which he defined as the ecology of human development. His association with Cornell spanned almost 60 years, and his legacy continues through Cornell's Bronfenbrenner Life Course Center and through the generations of students to whom he was an inspiring teacher, mentor and friend."

Francille Firebaugh, professor and dean emerita of Cornell's College of Human Ecology, commented: "Urie's introductory class, the Development of Human Behavior, was legendary, and his ability to make complex ideas readily accessible and stimulating was evident in his teaching and his writing. He loved Cornell and he was the faculty member most alumni asked about in my years as dean."

Born in Moscow in 1917, Bronfenbrenner came to the United States at the age of 6. After graduating from high school in Haverstraw, N.Y., he received a bachelor's degree from Cornell in 1938, completing a double major in psychology and music. He went on to graduate work in developmental psychology, completing an M.A. degree at Harvard University followed by a Ph.D. from the University of Michigan in 1942. The day after receiving his doctorate he was inducted into the Army, where he served as a psychologist in a variety of assignments in the Air Corps and the Office of Strategic Services. After completing officer training, he served in the U.S. Army Medical Corps. Following demobilization and a two-year stint as an assistant professor of psychology at the University of Michigan, he joined the Cornell faculty in 1948, where he remained for the rest of his professional life.

In addition to his wife, Liese, he is survived by six children, including Kate, who is the director of labor education research at Cornell, and 13 grandchildren and a great-granddaughter.

In lieu of flowers, the family has requested that donations be made to the Bronfenbrenner Life Course Center or to the Albert R. Mann Library, both at Cornell.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe