Teens more likely to eat breakfast if visited by virtual 'pets'

By Stacey Shackford

A fake Fido can motivate your child to eat breakfast, reports a new study. In a Cornell experiment, researchers found that teens who received feedback from virtual pets on a smartphone about their morning food choices were twice as likely to eat breakfast.

The study -- one of the first to test efficacy of mobile technologies to motivate adolescents to make healthy nutritional choices -- was published Nov. 30 in the Journal of Children and Media (5:4).

Eager to find a way to reverse the unhealthy trend of skipped breakfasts among older children where other campaigns had failed, first author Sahara Byrne, assistant professor of communication, and her Cornell co-authors -- including Geri Gay, professor of communication; Brian Wansink, professor of marketing -- used mobile phone games.

"This type of technology meets kids where they like to be -- on their phones. We're interested in how messages delivered through mobile technology can overcome resistance to health messages," Byrne said.

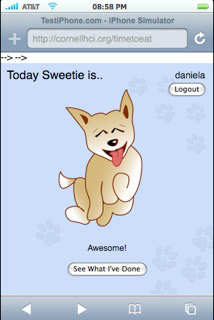

The experiment involved 39 adolescents in seventh and eighth grades for nine days. Given Apple iPhones activated with a virtual pet care game in the style of the popular Tamagotchi or Nintendogs, the participants were asked to choose and name an avatar -- dog, dinosaur, penguin, potato, stapler, robot, tree, worm or hippo. They then received an email from their "pet" each morning, prompting them to eat breakfast and record their choices using the phone's built-in camera.

Trained Cornell undergraduates scored the photos based on the healthiness of the meal, and responses were sent to the phones of participants within an hour. Based on the score, the player's pet responded to an algorithm that caused it to display a range of five emotions, from sad to happy.

Some participants received only positive feedback from their pets, regardless of what they ate, and others in a control group were asked to record their morning meals without playing the game.

The researchers found that those who received both negative and positive feedback from their pets were much more likely to eat breakfast. The healthiness of those breakfasts did not differ much, however.

"Our game allowed users to essentially care for themselves in the form of a cute creature," Byrne wrote in the paper. "The pet provided negative feedback without criticizing the user directly. Teenagers may have eaten breakfast simply to avoid seeing their pet be sad, which motivated new habits and behaviors without direct confrontation to self or identity."

She added: "This technology holds great promise in the area of nutrition and public health."

Byrne suggested that next steps could include: adding such features as social networking and competitions between individuals or teams; expanding the size of the study; conducting it across different cultural and socio-economic contexts; testing its efficacy over a longer period of time -- months or even years. It would also be valuable to test whether similar tactics could be used in other behavioral contexts, such as academic performance or exercise, she said.

The study was supported, in part by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Stacey Shackford is a staff writer for the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe