Carl Sagan and the Dalai Lama found deep connections in 1991-92 meetings, says Sagan's widow

By Melissa Rice

Religion and science do not have to be at odds. Science, said Ann Druyan, widow of Cornell astronomer Carl Sagan, can communicate with, learn from and even benefit from religion and vice versa.

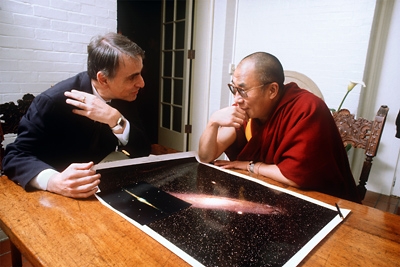

Druyan, a writer and media producer who collaborated with Sagan for 19 years until his death in 1996, reflected on dialogues in the early 1990s between Sagan and the Dalai Lama at a Sept. 28 lecture in Anabel Taylor Auditorium. For the first time, film excerpts of the meeting between the two were shown in a public venue.

Sagan, Cornell professor and author of "Cosmos," "Contact" and "Dragons of Eden," among other books, was perhaps best known for his extraordinary ability to communicate science to the public. "He wanted to share with everyone the wonder and awe that science inspired in him," Druyan said.

She stressed that there were political motivations behind Sagan's work as well: "Carl believed that you can't have a democratic society if you have a tiny scientific elite and a public who is uncomfortable with the methods and language of science," she said.

Sagan entered the public eye in the 1960s -- a time rife with changes in both culture and thought. The Catholic church had just switched from giving masses in Latin to local languages so that everyone could understand them, and Druyan said Sagan was trying to do the same for science.

The Dalai Lama, who has had a lifelong interest in science, first met with Sagan during a visit to Ithaca in 1991. Their discussion continued in India the following year, where the Dalai Lama cleared his calendar to spend a full day talking with Sagan and Druyan.

In the short segment shown of their conversations, Sagan asked the Dalai Lama about his beliefs in God and what he as a Buddhist would do if a discovery in science conflicted with Buddhist doctrine. The Dalai Lama replied that even Buddha was said to question his teachings and that Buddhists rely on doctrine as "findings" rather than as "scripture."

"If through thorough investigation things become clear, only then is it time to accept and believe," he said.

"So is there no conceivable scientific finding that would make you no longer consider yourself a Buddhist?" Sagan responded.

The Dalai Lama said there would be no point at which his spirituality and his respect for science would come at such odds with each other. "Buddhism is not so much a religion, but a 'science of the mind' or an 'inner science' ... there is much benefit to learning from [scientists'] findings," he explained.

Regarding the contributions of religion to science, Druyan said that while science has developed an amazing library of facts, it does not have the human social organization and the ability to inspire that religion has. That's why we have lost that magical excitement with space exploration that the world once shared, she said.

What science needs are more ambassadors. "We don't have a Carl Sagan right now," she said -- a well-informed, ethical and passionate leader, versed in the arts and sciences, concerned about the planet yet willing to "get into any kind of trouble for the sake of the human future."

Druyan's lecture was one of many events on campus prefacing the Dalai Lama's Oct. 9 visit to Cornell. Many of the ideas she discussed are put forth in Sagan's latest book, "The Varieties of Scientific Experience: A Personal View of the Search for God," which she edited.

Graduate student Melissa Rice is a writer intern at the Cornell Chronicle.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe